-

According to reliable data, at least 45 per cent of school enrolment in India is already in private schools

The key perhaps lies in the fact that while speaking about 6 per cent funding, neither the NEP nor the government has said anything about whether it will release the funds from its own pocket or generate it from private enterprises. Though no political party openly boasts about privatisation, it is now an important feature of the trajectory of Indian education over the past several years. Indeed there has been a low-key process of privatisation of the sector going on, unhindered. (This corresponds to a steep relative decline of its public component which often gets highlighted.)

According to reliable data, at least 45 per cent of school enrolment in India is already in private schools. In higher education, the private sector dominance is greater. While a similar 45 per cent of college enrolment in India is now in private unaided colleges, another 21 per cent is in private aided institutions. It comes as no surprise then that there are over 350 private universities operating in India.

Greater privatisation is imminent. The “Committee for Evolution of the New Education Policy”, also known as the T.S.R. Subramanian Committee, which formed the basis of NEP, has already laid the groundwork for the involvement of the private sector. It suggested, for instance, that over the next decade, at least 100 new centres for excellence in the field of higher education needed to be established with private sector help. “A climate needs to be created to facilitate establishment of 100 such institutions in both private and public sectors over the next 10 years.

This may include brand new institutions, as well as existing institutions upgrading themselves to levels of excellence. To achieve this, a liberal and supportive regulatory environment will need to be put in place.… If a sponsor is willing to invest, say R1,000 crore over a five-year period and the proposal is accompanied by a broad, credible plan of action, full autonomy should be offered for choice of subjects, location, pedagogy, recruitment of faculty from India or abroad as well as freedom to fix tuition fees – with the proviso that over a five-year period the new venture will be subject to careful scrutiny by the official accreditation/evaluation agency.”

That there is an unwritten thrust on privatisation in the NEP is evident from the guarded efforts of HRD minister Ramesh Pokhriyal Nishank to deal with such concerns. “All institutions, public and private, shall be treated on a par…the regulatory regime shall encourage private philanthropic efforts in education. At the same time, it shall closely monitor and eliminate commercialisation of education,” he says.

Digital = private

Nishank may soft-pedal the idea but there is another reason why the private sector’s involvement has become necessary. Over the past few months, the Corona virus pandemic has changed the education landscape across the world. Alternative, innovative modes of knowledge transfer, be it home-schooling or online classes, have been evolved. Video conferencing through Zoom helped students, as has learning on WhatsApp messenger and email. In just a couple of months, learning consortiums and coalitions have taken shape, with diverse stakeholders – including governments, publishers, education professionals, technology providers, and telecom network operators – coming together to utilise digital platforms as a temporary solution to the crisis.

-

Serving up a screen at the Doon School

In a way, India wasn’t totally unprepared for the Covid-19 crisis. Local online education start-ups like BYJU’s and Unacademy were already operational across India, offering innovative, interesting, interactive, and fun-based learning modules to school-going children to supplement and reinforce their learning. BYJU’s and Unacademy are both headquartered in Bengaluru and include prominent investors such as Sequoia and General Atlantic. This could become an increasingly prevalent and consequential trend to future education.

Many institutes are planning to develop a new cloud-based, online learning and broadcasting platform and upgrade education infrastructure. But experts believe that this kind of innovation will have to go beyond the typical government-funded or non-profit-backed social projects. Already, we have seen considerable interest, and investment, coming from the private sector in education solutions and innovation by way of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Reliance, Wipro, Bajaj Auto, Tata Steel and Infosys are among the leading players in this connection.

Digital education

Besides, education is key to growth. This is a global phenomenon. From Microsoft and Google in the US to Samsung in Korea to Tencent, Ping An, and Alibaba in China, corporations are awakening to the strategic imperative of an educated populace. This will happen in India as well. The Modi government will have to cash in on this situation, if it is serious about implementing the NEP full-scale. Rightly so, the NEP emphasises on digital education and remote learning. This has opened the doors for the future of what is called edtech.

However, while all education now happens online, when it comes to examinations, the situation may not be as crystal clear. For instance, Delhi University (DU) is planning to conduct online exams for its 2.5 lakh final year students. There’s a cloud of uncertainty on whether this is the most inclusive way of enabling online learning. The feasibility of the DU online exams has been questioned by the students and professors alike and after two months of student protests, the matter is now being discussed in the Delhi High Court. The disparity in access to the internet, electricity, and devices like computers or smartphones has also emerged as the major reasons for students unable to access online classes. Online learning content will need to be available in regional languages as well. NEP rightly proposes virtual labs, a National Educational Technology Forum which should help bring up more technological interventions in primary and higher education.

-

From Microsoft and Google in the US to Samsung in Korea to Tencent, Ping An, and Alibaba in China, corporations are awakening to the strategic imperative of an educated populace

An analysis of NEP 2020 by CARE Ratings underlines the dilemma of the digital thrust. It points out that while the NEP 2020 aims to increase digital mode of education in the country, this requires additional funding for schools. “Two main sources for sourcing finance would be government aid and increasing school fees. Raising school fees will indirectly add to the existing challenge of high dropout rates, especially in rural areas where dropout rates are high. Therefore, the government has a greater responsibility to motivate students and parents to continue staying enrolled in the education system for betterment of themselves, their family and the country.” The involvement of the private sector can certainly bridge the financial gap.

Need for NEP

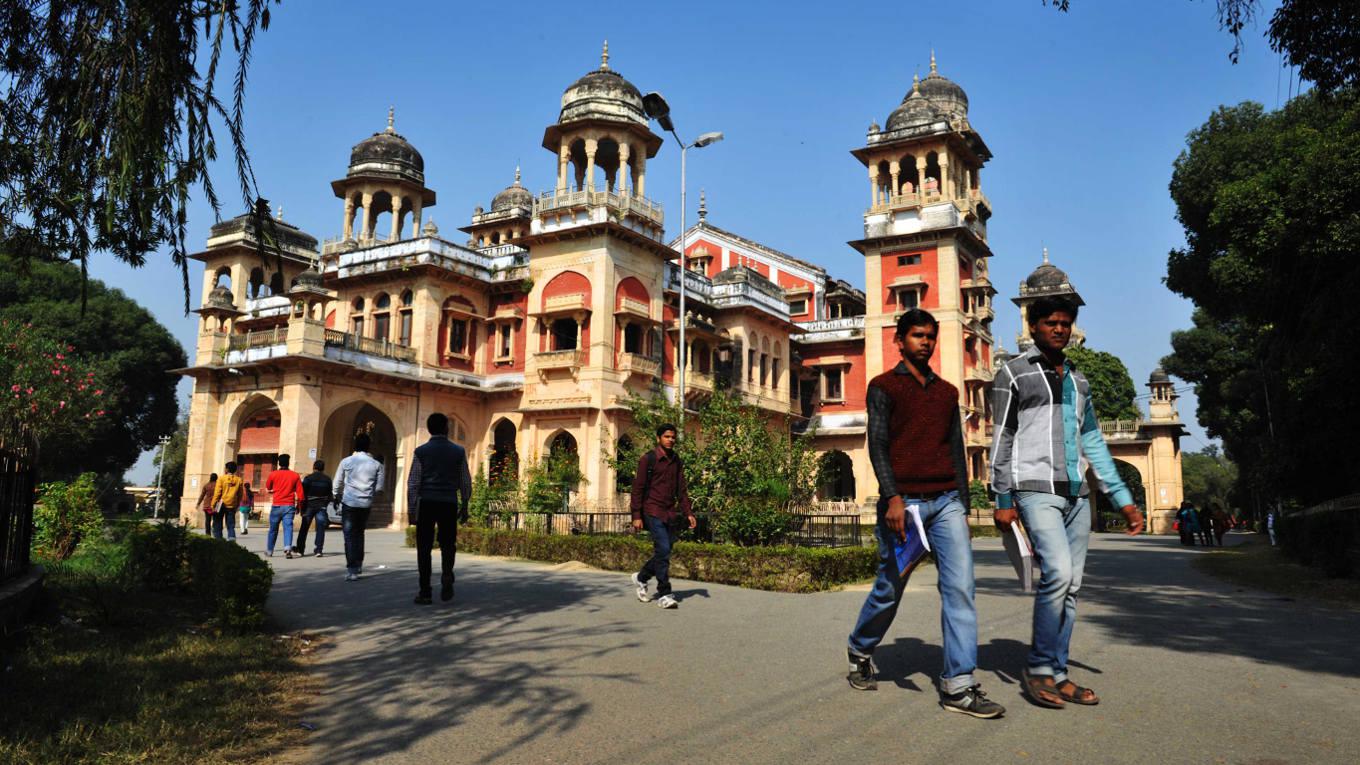

The need for an NEP was first felt in the 1960s and an Education Commission, led by D.S. Kothari, ex-chairman, University Grants Commission, was set up. Based on the suggestions of this Commission, Parliament passed the first education policy in 1968. The second policy came in 1986, under Rajiv Gandhi. The NEP of 1986 was revised in 1992 when P.V. Narasimha Rao was Prime Minister. The third is the latest NEP released under the Prime Ministership of Narendra Modi.

Two drafting committees – one led by former cabinet secretary T.S.R. Subramanian and the other headed by former ISRO chief K. Kasturirangan – have been associated with the NEP. Work on the new NEP began in 2015 and the first draft led to concerns that a massive “saffronisation” of education was on the cards.

Pragmatic policy

However, though the new policy has been welcomed by the Rashtriya Swyamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological mentor of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, it is marked by pragmatism. In fact, a number of suggestions – from ‘easier’ boards to a single higher education regulator, entry of foreign universities and even a four-year undergraduate programme – go back to the UPA era.

Only some of the RSS’s suggestions have been incorporated in the final version. For instance, the change in the name of Human Resource Development (HRD) ministry, coined by the Rajiv Gandhi government, to a simple Ministry of Education has the RSS stamp on it.

The other big recalibration is on language. Within days of NDA-2 taking charge, the draft Kasturirangan Committee report on the NEP had sparked off an uproar over its suggestion for mandatory teaching of Hindi in non-Hindi speaking states. Within two days, amid vociferous opposition, led by Tamil Nadu, the Centre replaced the contentious clause, doing away with all mention of Hindi vis-a-vis the three-language formula.

NEP 2020 now talks of ‘greater flexibility’ in the formula clarifying that “no language will be imposed on any state”. The impact of the RSS on the NEP is now limited to primacy given to mother tongue in teaching.

As things stand today, for private schools, it’s unlikely that they will be asked to change their medium of instruction. The provision on mother tongue as medium of instruction is also not compulsory for states. “Education is a concurrent subject. Which is why the policy clearly states that kids will be taught in their mother tongue or regional language ‘wherever possible’,” an official said. In fact, the three-language formula avoids the demand that Hindi should be considered as one of the languages that students should study in Class 6. All in all, three languages are to be taught to all students and while states are allowed to decide what to pick, two of these languages have to be native to India.

-

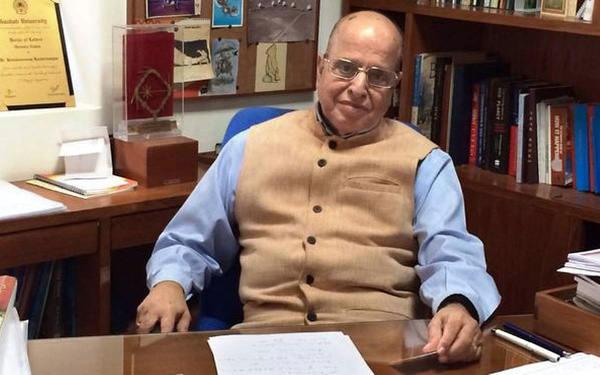

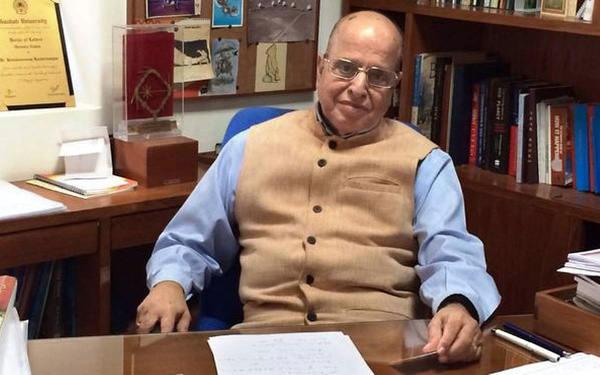

ISRO chief K. Kasturirangan

The NEP also has some elements which aren’t close to the Sangh’s heart. And the government has undertaken a balancing act to accommodate them partially or ignore them completely. The Swadeshi Jagran Manch, a part of the RSS family, was opposed to the entry of foreign universities and education institutions. The government, however, has allowed the entry. However, some riders like the NEP tenets being made mandatory for permission to operate have been incorporated.

School education

In school education, the policy focuses on overhauling the curriculum, “easier” Board exams, a reduction in the syllabus to retain “core essentials” and thrust on “experiential learning and critical thinking”. In a significant shift from the 1986 policy, which pushed for a 10+2 structure of school education (10 years of primary and secondary education followed by 2 years of higher secondary education), the new NEP pitches for a “5+3+3+4” design corresponding to the age groups 3-8 years (foundational stage), 8-11 (preparatory), 11-14 (middle), and 14-18 (secondary). This brings early childhood education (also known as pre-school education for children of ages 3 to 5) under the ambit of formal schooling. The mid-day meal programme will be extended to pre-school children.

The government believes that the NEP is recasting the existing structure of India’s K-12 education. As for the misconception that since 5+3+3+4= 15, students are now required to spend 15 years in school, the government believes that they already do. Most children (in cities) start their education by the age of 3 through playschools. The new structure is simply bringing playschools into the formal education ambit, and dividing the school structure based on the developmental stages of children. So for the first five years, children aged 3 to 8 years will enter the foundational stage. Since maximum brain development happens at these ages, the curriculum will focus on learning languages, playing, and activities. After five years of this, these kids will enter grade 3, where the focus will shift to discovery, and interaction-based classroom learning. Linguistic and numeracy skills will be honed at this stage.

Impartial observers like Yamini Aiyar, chief executive of Centre for Policy Research, feel that the latest NEP has its finger on the pulse. “In its aspiration and in the policy framework it articulates, NEP is genuinely transformational. The document recognises the twin tragedies of a large proportion of children in elementary schools failing to attain foundational literacy and numeracy coexisting with an assessment system that tests “rote memorisation skills” and “requires months of coaching” to master. None of this is new to debates on school education in India. But what makes NEP more promising is the clarity of focus on the problem and the framework it lays out for foundational learning.”

Foreign varsities

The NEP talks of universities from among the top 100 in the world being able to set up campuses in India. However, none of this can start unless the HRD ministry brings in a new law that includes details of how foreign universities will operate in India. However, it is not clear if a new law would enthuse the best universities abroad to set up campuses in India. In 2013, at the time the UPA-II was trying to push a similar Bill, a survey had revealed that the top 20 global universities, including Yale, Cambridge, MIT and Stanford, had shown no interest in entering the Indian market.

Participation of foreign universities in India is currently limited to them entering into collaborative twinning programmes, sharing faculty with partnering institutions and offering distance education. Over 650 foreign education providers have such arrangements in India.

-

Education in rural India. Photo credit: Sanjay Borade

However, officials in the HRD ministry say that the homework for welcoming foreign universities was done with the initiation of the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), which recommends all institutions to make disclosures about their assets and their investments in these assets. Besides ranking, educational institutions going for national and international accreditations also help in streamlining their organisational objectives and long-term goals towards quality teaching and research. Now that NIRF rankings are more or less stable and educational institutes are aligning towards accreditations, it becomes easier for foreign players to invest in the domestic market. Most corporates have been able to secure university licences, some even without a campus. They can now look forward to joint ventures and other forms of partnerships with international universities.

Four-year multidisciplinary bachelor’s programme

Another initiative is a four-year, multi-disciplinary bachelor’s programme. This pitch, interestingly, comes six years after Delhi University was forced to scrap such a four-year undergraduate programme at the incumbent government’s behest. Under the four-year programme proposed in the new NEP, students can exit after one year with a certificate, after two years with a diploma, and after three years with a bachelor’s degree. According to V.S. Chauhan, former chairman, UGC, “Four-year bachelor’s programmes generally include a certain amount of research work and the student will get deeper knowledge in the subject he or she decides to major in. After four years, a BA student should be able to enter a research degree programme directly depending on how well he or she has performed… However, master’s degree programmes will continue to function as they do, following which student may choose to carry on for a PhD programme.”

Doing away with MPhil

Then there is the proposal to do away with MPhil. Experts feel that this should not affect the higher education trajectory at all. “In normal course, after a master’s degree a student can register for a PhD programme. This is the current practice almost all over the world. In most universities, including those in the UK (Oxford, Cambridge and others), MPhil was a middle research degree between a master’s and a PhD. Those who have entered MPhil, more often than not ended their studies with a PhD degree. MPhil degrees have slowly been phased out in favour of a direct PhD programme,” points out Chauhan.

Whither single-stream institutions The policy also proposes phasing out of all institutions offering single streams and that all universities and colleges must aim to become multidisciplinary by 2040. This means they’ll be expected to teach everything from arts, science, management, etc. under one roof.

-

Once selected into a college, students will enrol in a three or four year undergraduate degree, with an option of leaving whenever they want

That implies the death knell of single-stream institutions and introduction of multi-disciplinary institutions. Experts say that the IITs are already moving in that direction. IIT-Delhi has a humanities department and set up a public policy department recently. IIT-Kharagpur has a School of Medical Science and Technology. Some of the best universities in the United States such as MIT have very strong humanities departments. “Take the case of a civil engineer. Knowing how to build a dam is not going to solve a problem. He needs to know the environmental and social impact of building the dam. Many engineers are also becoming entrepreneurs. Should they not know something about economics? A lot more factors go into anything related to engineering today,” a former director of IIT-Delhi points out.

New thrust

The government believes that a key takeaway of NEP is the thrust on vocationalisation of education at an early stage. Once students get to grade 6, the pedagogy will evolve to more experiential learning in the sciences, mathematics, arts, social sciences and humanities. This is also when students will be introduced to vocational training – they’ll be taught technical skills that will allow them to take up jobs in specialised trades or crafts like pottery or carpentry. In fact, they’ll also have to do a 10-day internship with local experts. This will go on till students get to grade 9.

Of course, amid all these changes, something will have to be done about those career-defining assessments that make students everywhere tremble – board exams. Unfortunately, the policy does not discontinue board exams. But it does lower their importance and make them easier. What’s more, students will be allowed to take them again if they think there’s scope for improvement. Moreover, the National Testing Agency (NTA) will be charged with conducting (optional) entrance examinations for admissions into higher educational institutes across the country.

Once selected into a college, students will enrol in a three or four year undergraduate degree, with an option of leaving whenever they want. If you complete one year, you’ll get a certificate. Two years later, you will get a diploma. If you stick it out for three or four years (depending on the course), you’ll get a degree. And if you pursue a four-year programme with research, you’ll be an eligible PhD candidate.

Another innovative bit here is the Academic Bank of Credit (ABC). An ABC will store the academic credits that students earn by taking courses from various recognised higher education institutions. Whenever you complete a course, a number of credits will be added to your bank. You can then transfer these credits if you decide to switch colleges. And even if you’re forced to drop out for some reason, these credits will remain intact. This means you can come back years later and pick up from where you left off. So, the NEP offers a number of choices and chances to students through change. As education expert Meeta Sengupta says, “This is an NEP that offers Choice, Chance and Change.”

But as always, the key question is: how will all these reforms be implemented? The NEP only provides a broad direction and is not mandatory to follow. Since education is a concurrent subject (both the Centre and the state governments can make laws on it), the reforms proposed can only be implemented collaboratively by the Centre and the states. This will not happen immediately. The Modi government has set a target of 2040 to implement the entire policy. Sufficient funding is also crucial; the previous NEPs were hamstrung by a shortage of funds.

The government says it plans to set up subject-wise committees with members from relevant ministries at both the Central and state levels to develop implementation plans for each aspect of the NEP. The plans will list out actions to be taken by multiple bodies, including the HRD ministry, state Education Departments, school Boards, NCERT, Central Advisory Board of Education and National Testing Agency, among others. Planning will be followed by a yearly joint review of progress against targets set. Twenty years is a lot of time to fully implement the NEP targets.

And so, while the Modi government has generally been lauded for grasping the nettle on education, many feel that it would have to scale down the targets to make them more realisable. Also, the Centre will have to cajole and entice the states to make the NEP a success. That may be a tall order.