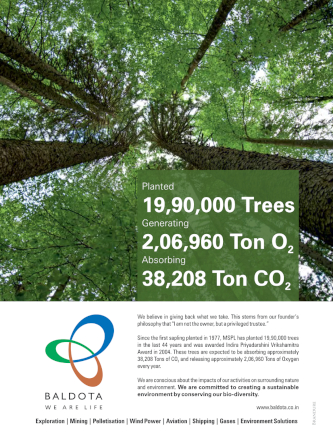

A few western philosophers during the Enlightenment era in the 17-18th century proposed a highly influential theory of nature that views the natural environment as a means to an economic end — a resource to be used and controlled to benefit human endeavour. This worldview has shaped generations of global development models and continues to underpin current notions of ‘progress and development’ in many parts of the world. It has influenced how we value nature’s ecosystem services, and it has also influenced policy making and corporate agendas putting human economic needs ahead of the need to preserve and nurture natural ecosystems, not realising that, without nature, humans cannot actually exist. As a result of this centuries-old unequal relationship, humans now exist in a precarious state with nature. For instance, take the example of fishing communities in the Arabian Sea region, accustomed to earning a sustainable livelihood for ages, are now facing a threat of livelihood loss due to a sharp increase in incidents and intensity of cyclones. There has been a 52 per cent increase in the frequency of cyclones in the Arabian Sea over the the last two decades. This has meant rougher seas which, in turn, reduce the time available for fishing, thereby hurting revenues and profit. Nature’s sturdy supply chains are also being disrupted simultaneously as rising temperatures force some fish species into deeper seas and new habitats, making sustainable fishing a tougher challenge. Alongside the loss of traditional knowledge, the fishing communities are also unable to use traditional practices. Rising sea levels and greater soil erosion has meant that there is not much beach left to dry fish on. The fish rots, leading to wastage and further economic loss. In 2022, India and much of the globe have faced more disruptive weather phenomena — heatwaves, floods, with unprecedented rainfall in some areas and droughts in others. Traditional cropping seasons have been disrupted, affecting sowing and harvesting patterns. Extreme climate events have already led to deaths, huge economic losses and exacerbated health problems which, in the longer term, will severely impact our food and water security. These ‘slow onset events’, driven by climate change (rising sea-levels, soil erosion and melting glaciers), are resulting in an acute loss of bio-diversity as well as loss of livelihoods. If India is to achieve its commitments under the Paris Agreement to achieve ‘net zero’ by 2070, we must drastically change this paradigm and learn to coexist harmoniously with nature, rather than try to control it to further our economic progress. Reversing nature loss requires us to ‘bend the curve’ by rebooting many aspects of business and policy as well our lifestyles. The problem of nature loss is more than immediate. The big banner success of ‘Project Tiger,’ for example, is a widely celebrated successful conservation story, which has generated tremendous awareness about tigers and their habitats. However, this success hides a more disturbing trend. Research indicates at least 97 mammals, 94 bird species and 482 plant species in India are threatened with extinction. Most of these species will go extinct without us ever appreciating the true price future generations will pay for this.