-

While Manmohan was the architect of the reforms, Rao provided the political ballast

Freeing the stranglehold

There is no doubt that the freeing of regulatory stranglehold in large sectors of the economy has, over the years, seen an improvement in the ease of doing business. A new generation of entrepreneurs and small businesses has come up. New wealth has been created. Financial inclusion has opened up new opportunities.

According to World Bank, India’s GDP stood at $2.62 trillion in 2020 (in current dollar terms), which is tenfold larger than what it was in 1991 at $270 billion. Per capita GDP, which was at $303 in 1991, is now close to $2,000. Forex reserves, which were barely enough to cover three weeks of imports in June 1991, crossed $600 billion for the first time in June this year. There was a time when India had to pledge its gold reserves to secure a $400 million foreign debt. Now, no foreign investor worth his capital can afford to ignore India. This is reflected in the almost $82 billion of FDI received in 2020-21.

Clearly, there have been other positives as well. The quality of life has generally improved. The growth we witnessed post-reforms has dramatically reduced poverty. According to UNDP, a record 273 million people were lifted out of poverty in one decade (2005-16).

P. Chidambaram, former finance minister, recently wrote how 30 years ago, there was one domestic airline (Indian Airlines), two telephone service providers (BSNL and MTNL), three cars (Ambassador, Fiat and Maruti) and numerous waiting lists for a telephone, gas connection, scooter etc. There were many scarce articles and commodities, the scarcest being foreign exchange. He remembered travelling to the US to study for a Master’s degree on $7 a day for only 10 months a year! Such sentiments are being widely echoed by others as well.

Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, MD, Bandhan Bank, recalls: “Those like me who have lived in and remember how India was before 1991, distinctly remember how one would have to wait for months (sometimes even years) to get a landline connection at home or an LPG gas connection. Today, one cannot imagine life without a smartphone, which powered by data and digital technologies serves as a gateway to the world.” Notes N.K. Singh, chairman, 15th Finance Commission: “It is hard to even recall the limited choices we had for infrastructure, services and goods in 1991 in comparison to what we have today”.

Lurking reservations

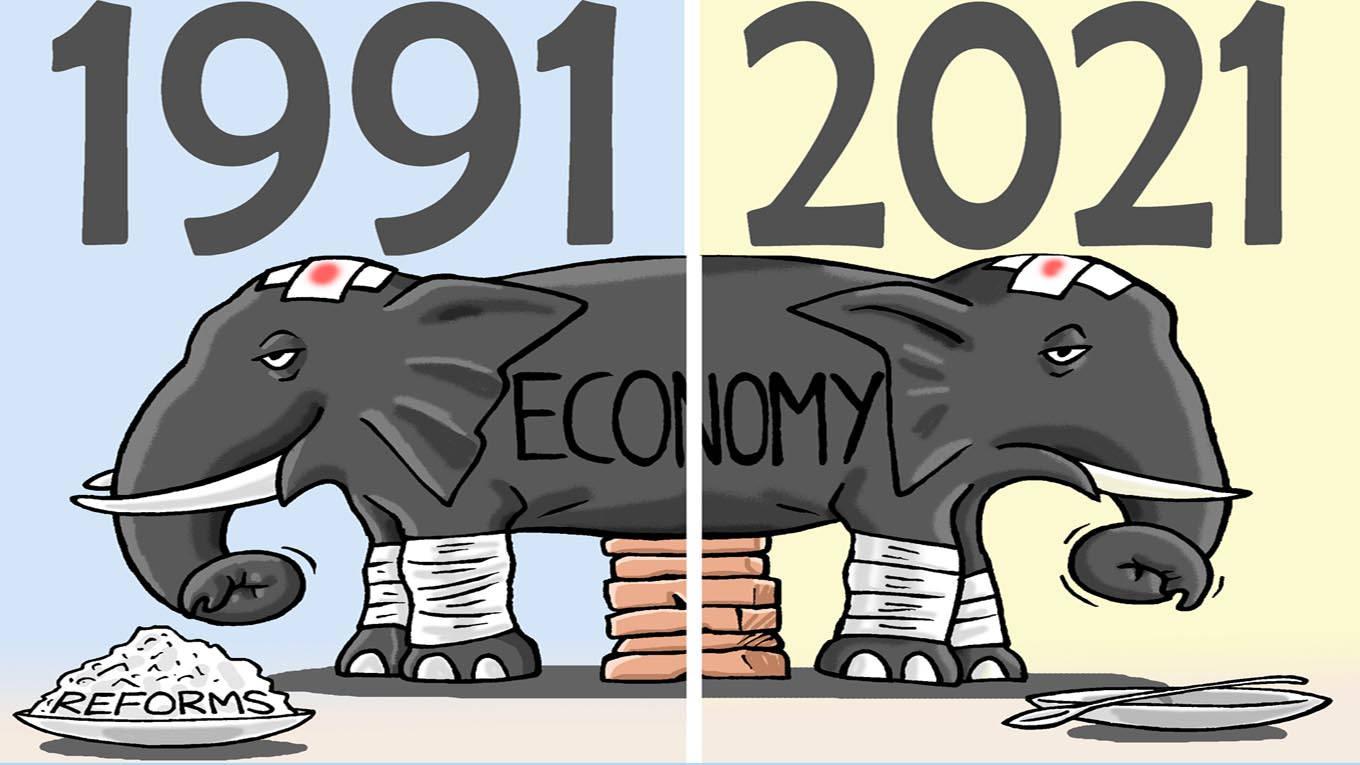

However, over the years, as the economy grew, so did the need for more reforms. As it happened, the reforms process did not keep pace with the economic expansion. When the shadow of Covid-19 fell on India last year, the economy was already slowing down. The shuttering down of business establishments to check the spread of virus led to a severe contraction of the economy. The damage has spawned lurking reservations on what lies ahead.

Not many people in the government are talking of the pre-pandemic official goals such as double-digit growth and making India a $5 trillion economy by 2024. The NITI Aayog Index shows there has been a major decline in areas of industry, innovation and infrastructure, besides work opportunities and economic growth, made worse by lockdowns imposed to tackle the pandemic.

There is also a view that India’s growth story may have already peaked and a new thrust on reforms is required to recapture the momentum. While the period between 2001-02 and 2011-12 was the best in terms of economic growth, followed by the two decades before, the decade from 2011-12 to 2021-22 was the worst in terms of GDP growth in the post-reform period. This is a result of the slowdown since 2016-17 and the pandemic-driven contraction in 2020-21 and most possibly the current year.

Then, there are the problems bedeviling businesses, which predate the pandemic. Take the case of the MSMEs sector, the biggest creator of jobs in India. The sector faces a serious challenge in the limited availability of formal credit. The pandemic has exacerbated this situation as risk aversion has taken hold. The government needs to double down on MSMEs-focussed credit guarantees.

While the government’s Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme programme has infused guarantee capital of Rs3 lakh crore in the last year, more can be done to help Non-Banking Finance Companies in particular, who are the principal credit providers to the MSME sector.

-

Thirty years ago, there was one domestic airline (Indian Airlines), two telephone service providers (BSNL and MTNL), three cars (Ambassador, Fiat and Maruti) and numerous waiting lists for a telephone, gas connection, scooter etc

There is also over-regulation. For a small entrepreneur, operating in the best of times requires regularly overcoming regulatory hurdles. It may come as a shocker but research by Avantis shows that a typical MSME has to file over 750 compliances every year. The reforms here must be based on issued as varied as decriminalisation (of minor offences), rationalisation of compliances (such as reducing the number of labour registers to be maintained), digitisation of processes, and reducing bureaucratic discretion. The states will have to lead the initiative.

To launch a new generation of reforms, the Modi government will have to give up its policy of policy of centralisation and win over the states to bring them on board the reform process. Take the disinvestment and asset monetisation programmes. The current mood prevailing among some political parties, trade unions and opposition-ruled states is clearly against privatisation and sell-offs. Early this year, the Centre sought the support of states for these programmes, as well as the national infrastructure pipeline projects, because support of law and order machinery in states is critical for carrying out these programmes.

Besides, the states’ machinery is essential for removal of encroachments and encumbrances, change of land use and facilitating no objection certificates. In any case, most of these assets have been built with the support of states on land acquisition and other statutory clearances. Clearly, the states will develop a stake in the reforms process only if they are given a share of the proceeds of divestments and asset monetisation. The Centre can then step in to guide the states in privatising their own PSUs and carrying out asset monetisation of projects and installations.

While the state of most Central PSUs and why these need to be privatised is well documented, the story of some 1,300 state government-owned entities remains hidden. Out of these, about 1,000 are said to be operational. Most of them are functioning without any business plan or marketing policy. The losses accumulated by state PSUs stood at a huge Rs97,000 crore in 2019 – three times more than the Central PSUs. In Uttar Pradesh alone, 38 of the 103 state PSUs, which operate in areas as diverse as piggery, warehousing, police housing and sundry small industries, are non-functional. Why can’t the Centre hand-hold the states in privatizing these PSUs? The private sector can easily discharge their role. That will be real reform.

Montek’s recipe

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, a key figure in India’s reforms process, says that the best way to commemorate the 1991 reforms is to consider what we can learn from them in dealing with the current crisis. “The 1991 strategy had two components – reducing the fiscal deficit and implementing structural reforms. Both are relevant today, but with differences,” he recently pointed out.

Ahluwalia’s thesis is predicated by the fact that reducing the fiscal deficit was essential in 1991, because it was an obvious way of containing demand. The 1991 crisis was caused by excess domestic demand sucking in imports and widening the current account deficit (CAD). A loss of confidence triggered an outflow of funds and financing CAD forced a sharp drawdown in reserves. The crisis today is not caused by excess demand. It has been triggered by a collapse in production, following the disruption caused by the pandemic, which, in turn, has caused a fall in demand. Those who lost incomes had to cut consumption. Even those who have not lost income face uncertainty and have postponed expenditure.

-

Ahluwalia: the 1991 strategy is still relevant

Ahluwalia, who headed the Planning Commission during the UPA years, says that investment, a key source of aggregate demand, has also slowed because of unutilised capacity and uncertainty about growth. Hence, it is appropriate to increase the fiscal deficit. He endorses the government’s move to allow the fiscal deficit to expand to 9.6 per cent last year, though some of this was statistical, reflecting the inclusion of off-budget items. The question is whether this year’s Budget Estimate deficit of 6.8 per cent for 2021-22 is appropriate.

He feels that the government should definitely maintain expenditure at the levels budgeted and let the fiscal deficit rise, if it has to. There is also a strong case for providing more funds for vaccination, which is key to reviving growth, and also to cover expanded demand for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, which is proving to be a valuable safety net.

Focussed reforms

As for reforms, Ahluwalia says that an important lesson from 1991 is that the governments need to move away from a ‘long list of reforms’ approach towards a more strategic approach, focussing on the most critical reforms needed immediately. He puts banking sector reforms right at the top since our banking system is heavily dominated by public sector banks (PSBs) and genuine reform in this area is not in sight. Here are some reforms suggested by him and how to go about it:

• Bank mergers may help reduce branches, and perhaps monetise excess real estate to boost capital, but it is not a systemic reform. A serious reform would be vesting the government’s equity in PSBs into a holding corporation run by a board of independent professionals, which then appoints the top management.

• The Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC) is a key reform, but its operation was temporarily put on hold because of the pandemic. The government can play an important role in signalling to the courts that IBC is a flagship reform that should not be undermined.

• The crowding out of private investment may not be relevant today because investment sentiment is depressed but, in the long-run, making room for expanded private sentiment is essential. This calls for fiscal consolidation for next year onwards, which will require greater buoyancy in tax revenues.

• The need for buoyancy in tax revenues calls for a second look at the Goods & Services Tax (GST) regime. GST was expected to generate greater tax buoyancy but it has not done so. Its rate structure and exclusions need to be reviewed. An important lesson from 1991 is that tax reforms are best evolved by an expert group outside government. Such a group should be set up and asked to review the experience so far, and make proposals for reform which could be discussed in the GST Council. This cannot be left to the revenue department.

The above suggestions should not be dismissed lightly, as they come from a person who authored the once-famous ‘M Document’, which laid the ground for the basic thrust of the 1991 reforms. Such ideas and more may become necessary if we are to at all aspire for double-digit growth.

-

The 1991 strategy had two components – reducing the fiscal deficit and implementing structural reforms. Both are relevant today, but with differences

Services to the fore

The post-reforms growth story by sectors shows that services, not manufacturing, have been the bigger beneficiary of economic reforms in India. The services sector accounts for almost 54 per cent of the GDP. The share of manufacturing in GDP has not changed significantly over the last 30 years. It was 15 per cent in 1990-91, reached a peak of 18.4 per cent in 2017-18, came down to 17.1 per cent in 2019-20 and further down to 16.9 per cent in 2020-21. This skewed development had left a huge imbalance.

Growth per se in any economy does not guarantee well-being for all. For the people at large to experience an improvement in living standards, additional incomes need to accrue to a large majority. If a small minority is engaged in highly productive (and paying) work while the bulk of the workforce is employed in subsistence level sectors, an economy can continue to experience a high growth rate and poor living standards for a majority. The Indian economy currently fits this description. At least 40 per cent of India’s workforce is still engaged in agriculture, even though this contributes less than 15 per cent of the total GDP.

Successive governments have talked about getting people out of agriculture to non-agriculture sectors to boost employment. It is only when fewer people depend upon agriculture that per capita incomes in agriculture will rise significantly and sufficiently to make farming an attractive proposition. While the Chinese example wherein industrialisation was used to employ millions of people leaving farms during 1992-2012 comes to mind, it must also be remembered that compared to China, India falters on all four major components of industrial competitiveness – energy costs, costs of capital (borrowing or raising money), logistics & supply chain and labour (including skills).

Since it is hard to beat China on these four parameters, India needs to focus on its niches, its domestic needs and gaps that global players might not be filling. This will call for a recalibration of programmes like ‘Make in India’ and ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’. One cannot simply manufacture anything and everything under the sun without the burden of economic logic, facts and evidence.

Nilesh Shah, MD, Kotak Mahindra Asset Management Co, sees a lot of potential in the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for 13 sectors like electronics, electricals, mobile phones, automobiles and textiles. This scheme can be a game-changer, if implemented properly. “Through this scheme, we can bring global companies to India. It will create manufacturing employment and that will support domestic employment and global employment too.”

Shah cites the success of Samsung, which began by manufacturing its product for sale in India only. Today, Samsung is the biggest consumer durable company in India with a turnover of $12 billion. However, he points out that, in Vietnam, Samsung’s turnover is $60 billion. Vietnam is one-tenth the size of India’s GDP, but the same company has five times the turnover as that of India. India can do a lot of catching up with such schemes.

-

Singh: we had limited choices

From Rao to Modi

The 1991 reforms, anchored by the team of P.V. Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh, were driven by compulsion, though a tentative process of modernisation had begun during the reign of Rajiv Gandhi. Post-Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee carried forward the reforms to the best of his ability and also sowed the seeds of two reforms, which form the bedrock of a growing, modern economy – GST and fiscal reforms.

Surprisingly, Manmohan, in his avatar as prime minister, steered a middle-of-the-road policy under pressure from the constituents of the then ruling United Progressive Alliance and the Communists, who were providing support to the ruling coalition during his first term. Indeed, the bulk of India’s substantive economic reforms were carried out during the Rao-Manmohan and Vajpayee years.

The record of Narendra Modi, despite his overwhelming electoral mandate in 2014 and 2019 and his past reputation in Gujarat as a doer, has been a mixed bag, at best. He started off by attempting to overhaul the land acquisition law, failed to push the legislation and then went into a shell of sorts. It is difficult to figure out what exactly made him go slow on reforms, considering that he could have fired up the nation’s imagination by doing so. Some attribute it to the late Arun Jaitley, his cautious confidante-cum-finance minister, who was mostly guided by bureaucrats.

Others like the BJP’s maverick Rajya Sabha MP Subramaniam Swamy feel that it is his poor grasp of economics that let him down. Perhaps it was Rahul Gandhi’s jibe about him running a suit boot ki sarkar and the BJP’s loss in the 2015 Bihar assembly election that made him cautious. It is only after six years in office when the Covid-19 pandemic ravaged the economy and the faltering growth numbers threatened to become a political liability that Modi has been forced to rethink on economic strategy.

In September last year, the Modi government passed three bills that seek to the monopoly of government-controlled market yards, where farmers sell crops through middlemen instead of directly to private buyers, and scrap rules limiting grain storage that have hamstrung investment in agriculture. The farm reforms provoked a major backlash from farmers in Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh.

The government’s heavy-handed response to protests escalated the tension, though the protests are now petering out but could play out during the upcoming assembly elections in these states. It is possible that Modi and his political team will watch the outcome of these elections before going full steam with the implementation of these reforms.

Long history

The BJP credits the implementation of the GST to the Modi government but this was a law mooted 17 years ago. It is a different thing that Modi had a special midnight session of Parliament organised to roll out the law. Today, there are growing demands for the GST’s overhaul, because of the glitches, which have surfaced. Similarly, the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code, which has been suspended for a year owing to the pandemic, was an idea in the making for a long time.

But recent data from the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Board of India shows that the overall recovery rate in 348 cases, where the resolution plan was approved till March 2021, is just about 37 per cent. Also, out of more than 2,650 closed cases, 48 per cent went into liquidation. Moreover, as of March 2021, 79 per cent of the ongoing cases have been continuing for over 270 days, which goes beyond the timeline set for the process as per the IBC.

-

If we are looking at getting growth – of 8-10 per cent – back on a sustainable path, we have to think about not just a current revival

As for the much-touted labour reforms, 29 Central laws have been crunched into four ‘codes’. The codes give greater freedom to businesses when it comes to taking on and shedding employees, while putting trade unions to test about their representational claims, and making both strikes and lock-outs more difficult. Those employing fewer than 300 workers don’t even have to issue what are called standing orders, which specify conduct norms for workmen.

The labour law changes are a necessary, but not sufficient condition for achieving the intended objectives like greater production and employment generation. However, co-terminous changes are required to reduce the cost of factory land, transport, and electricity for industrial consumers (by ending cross-subsidies), while stopping the arbitrary interpretation of tax and other laws and maintaining an appropriate exchange value for the rupee.

Everybody seems to agree that infrastructure has been a bright spot in Modi’s report card. The government has been laying 36 km of highways a day on average, compared to his predecessor’s daily count of 8-11 km. Installed renewables capacity – solar and wind – has doubled in five years. Currently at about 100 gigawatts, India is on track to achieve its 2023 target of 175 gigawatts.

His schemes like new toilets to reduce open defecation, housing loans, subsidised cooking gas and piped water for the poor have been welcomed. But many of the toilets aren’t used or have no running water, and rising fuel prices have undone the benefit of the subsidy. Strict monitoring and follow-up of such well-intentioned schemes which benefit the poor will also amount to a reform.

Perhaps this is Modi’s moment to carve out his place in the economic history of India as a leader who fully liberated the economy. While his pro-poor schemes like financial inclusion, direct benefit cash transfer, toilet building and free cooking gas connections have got him the votes, his government’s record in spurring growth, creating jobs and now checking price rise has been remarkably lacklustre.

States’ co-operation vital

Like 1991, Modi needs to make 2021 a bellwether occasion for launching a new trajectory of reforms which erases the sharp conflicts between the centre and the states, particularly the opposition-ruled ones. Be it tax-sharing, apportionment of proceeds of disinvestment of PSUs located in various states, vaccine and oxygen shortages, which exacerbated the pandemic, Modi needs to reach out to the states in the true spirit of federalism.

After all, it is the business climate in individual states that drive job creation, more so than policies implemented by the central government in New Delhi In many instances, state governments can follow a different agenda than New Delhi, even if the same party is in power. Better policy decisions are required – along with coordination at the Central and state levels – to improve the conditions needed for job creation.

The trigger for the 1991 reforms was the balance of payments crisis. India’s forex reserves started depleting at a fast clip as we were suddenly forced to pay much more for its imports. By June 1991, India had less than $1 billion foreign reserves, just about enough dollars to meet about three weeks of imports, even after substantial borrowing from the IMF earlier in the year. By July, it looked like India would default on its international debt obligations.

Several factors had then combined to create the trigger – the disintegration of the Soviet trading system that terminated the bilateral rupee-rouble payment agreement, the Iraq-Kuwait War that led to a sharp rise on oil prices, the slowdown of India’s trading partners (the US, the Soviet Union and others), and years of unabated fiscal profligacy, compounded by the political instability of having three prime ministers (Rajiv Gandhi, V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar) between 1989 and 1991. It was then that push came to shove.

-

Sitharaman: a challenging task

Vajpayee years

Vajpayee too laid the basis of several reforms and carried forward the spirit of the Rao-Manmohan moment in 1991. For instance, while the Goods & Services Tax (GST) was implemented in India on 1 July 2017 under Modi, it was Vajpayee who had first mooted the idea of a common tax structure for goods and services across the country.

In 2000, the NDA government led by him had set up a committee to design the backbone of the GST model and ensure that the technology back-end was put into place. However, due to lack of consensus among the parties and individual states, the reform was delayed for as long as 17 years.

His government enacted the Fiscal Responsibility & Budget Management (FRBM) Act in 2003. The act set targets to reduce fiscal deficits and boost savings in the public sector. While there were several amendments made to the act, it was Vajpayee who brought forth the idea of keeping fiscal deficit under check at 3 per cent of GDP. It is a different thing that Modi after sticking to strict fiscal parameters has now been forced to take liberties with FRBM Act to provide a stimulus to the pandemic-hit economy.

Vajpayee also realised the importance of education in the growth of a nation. He set up the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan to provide free and compulsory education to all children between 6 and 14 years of age. The primary objective of the scheme, which commenced in 2000-01, was to reduce dropouts and increase the net enrolment ratio at primary level. With the mission in full force, the rate of dropouts reduced from almost 40 percent in 2000 to less than 10 percent in 2005. Like Rao, his tenure was marked with some distinguishing features:

Telecom reforms: If India boasts of a billion-plus active wireless phone users today, the credit for the same should go to Vajpayee. In 1999, his government took a decision to end state monopolies for entities like Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL) and introduced a new Telecom Policy where a revenue-sharing regime was started. This led to revenue sharing model and eventually paved the way for call rates getting cheaper as well as affordable mobile phones.

Disinvestment/privatisation: One of the flag-bearers of divestments in public sector undertakings, Vajpayee had set up a separate department for disinvestment under Arun Shourie as early as 1999. Under his leadership, large disinvestment initiatives, including that of Bharat Aluminium Co, Hindustan Zinc, as well as Videsh Sanchar Nigam, took place.

The insurance sector, until 1999, was dominated by state-owned entities in both life and general insurance segments. The sector was privatised to allow corporates to set up insurance companies. Foreign direct investment of up to 26 percent was permitted that led to several global insurance companies entering India. Co-incidentally, the Insurance Laws (Amendment) Act was passed in 2015 under Modi’s leadership that allowed foreign shareholders to hold up to 49 per cent stake in Indian insurance companies.

-

Vajpayee carried forward the spirit of the Rao-Manmohan moment in 1991

Why reforms now?

Early this year, all eyes were on the 2021-22 budget to be presented by Nirmala Sitharaman on 1 February. For a change, the budget did not play to the gallery. There are no new populist schemes creating permanent entitlements, despite talks of annual cash transfers, now any cuts or concessions for income tax-payers.

The budget did not levy any wealth tax or special cess/surcharge for financing the Covid vaccination programme, that the markets feared. Instead, the budget tried to give a step up in government spending at a time when private consumption and investment are languishing. Capital spending was up by 26 per cent to Rs5.54 lakh crore over the current fiscal year’s revised estimate of Rs4.39 lakh crore, which is 6.6 per cent higher than the original provision.

As for reforms, there were small flourishes. The entire food and fertiliser subsidy obligation was taken on the Centre’s balance-sheet, as opposed to the earlier obfuscation through forced off-budget borrowings by the Food Corporation of India and fertiliser firms. This made for a refreshing departure from the beaten path.

FDI limit in the insurance sector was increased from the existing 49 per cent to 74 per cent and privatisation of at least two state-owned banks and one general insurance company was targeted in 2021-22. The budget forecast a V-shaped recovery with GDP growth of 11 per cent. The RBI has pared this down to 9.5 per cent, rating agencies are even less optimistic with HSBC pegging it at 8 per cent.

However, Sitharaman had not reckoned that a second wave of the pandemic could make her task more challenging. RBI expects the economy to expand 9.5 per cent in 2021-22. We will soon know the growth figure for the first quarter. In 2020-21, the pandemic’s economic disruption forced a contraction of 7.3 per cent in the Indian economy in 2020-21. It was the first quarter, the period from April to June 2020, which fared the worst with a contraction of 24.4 per cent.

This was basically the result of the 68-day-long hard lockdown which was imposed from 25 March 2020 onwards. The economy recovered sharply in the third and fourth quarters, expanding by 0.5 per cent and 1.6 per cent respectively, resulting in the overall contraction for the year being lower than the expected 8 per cent.

Less impact, yet….

Many economists believe that the impact of the second wave has been softer than that of the first wave, most likely a result of the fact that there was no national lockdown. The V-shaped recovery in the Nomura India Business Resumption Index (NIBRI) is the closest to the narrative of the second wave’s economic impact being lower and short-lived than the first wave’s. NIBRI reached a peak of 99.3 in the week ending 21 February (100 indicates the pre-pandemic level).

It started slipping gradually over the next month to reach 94.6 in the week ending 28 March. Then, as the second wave gained momentum and mobility restrictions were re-imposed in most parts of India, NIBRI fell sharply to collapse to 60.3 in the week ending 23 May. The second wave reached a peak on 9 May in terms of the seven-day average of daily new cases. The last few weeks have seen a sharp recovery, the highest in terms of week-on-week change, and NIBRI reached 86.7 in the week ending 27 June.

-

The pandemic has set us back hugely, and we were already on a growth downswing, when it happened. Going forward, it all depends on how cleverly we design the way we come out of these doldrums

However, the June Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI)-manufacturing numbers have raised a red flag on the demand front. PMI for manufacturing was 48.1 in June. This is the lowest PMI manufacturing value since July 2020 and also the first time it has gone below the critical threshold of 50 during this period. A PMI value below 50 signifies a contraction in activity.

The June numbers are cause for concern because PMI manufacturing did not fall below 50 even in the months of April and May, when the pandemic was raging. This suggests demand side rather than supply side (which is what lockdown restrictions create) headwinds to economic activity.

The Capex numbers too have disappointed. Investment is among the biggest determinants of future growth. Whether or not businesses make investments depends on their assessment of the future prospects of the economy, which is what drives future demand. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) capex database shows that the investment mood continues to be subdued. The year-on-year growth numbers are impressive for the private sector, largely because of a base effect.

But new investment announcements, which are an important metric of business sentiment about future demand, continue to be at low levels compared to the pre-pandemic phase. What is also a matter of concern is a continuing weakness in new investment announcements by the government as well, which could be a result of strained state government finances. It is the states which have done most of the heavy-lifting during the pandemic.

We’re now in 2021. The Indian economy has witnessed several quarters of slowing and negative growth. For more than a year, the pandemic has loomed large over us, there is no guarantee that it will simply go away. And, Modi government is moving towards the half-way mark of its second term. While the economic situation is not as grave as in 1991, this government will need to come up with some strong reformative measures – perhaps along the lines of the ones proposed by well-meaning people – to prevent the economy from slowing down further.

As Indira Rajaraman, economist & former member, Reserve Bank of India’s board, says, “The pandemic has set us back hugely, and we were already on a growth downswing, when it happened. Going forward, it all depends on how cleverly we design the way we come out of these doldrums.” This is exactly what the government’s top economists like Sanyal are also saying. Such concord calls for immediate government action.

-

Like Singh, Modi is having his share of trouble

Manhohan v/s Modi

Given the abnormal times, comparisons about economic performance of successive prime ministers are odious. Like Singh, Modi is having his share of trouble not entirely of his own making. If Singh had to battle the domino effect of the global financial crisis, Modi has to cope with the pandemic’s dark shadow since last year

On the face of it, there is little doubt that Modi as PM has been running a tighter ship than what Singh did in terms of governance. This is mostly because of his centralised form of governance and lack of any extra-constitutional power interfering in his work. Yet, Singh stands tall over Modi as a reformer. The BJP-led dispensation has been no match for Singh as finance minister in the Narasimha Rao government in anchoring far-reaching structural reforms that invigorated the economy.

Modi’s reforms like demonetisation and a hastily stitched GST have caused major disruptions in the informal sector. He has been forced to keep the farm reform laws in abeyance because of farmers’ protests and the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code because of disruption wrought by the pandemic.

How have the two fared in helming the economy? In the first seven years of Singh’s tenure, GDP growth averaged 7.29 per cent. But GDP growth during Singh’s tenure declined sharply in the last three years averaging 5.8 per cent, bringing down the overall GDP growth during 10 years to 6.81 per cent.

The comparable number of Modi’s tenure during the last seven years is 4.72 per cent. This has been impacted adversely by the -8 per cent GDP growth in last financial year (2020-21) due to Covid. Excluding the abnormal year, GDP growth during Modi’s tenure improves to 6.84 per cent, marginally lower than Singh.

The Modi government scores much better on the inflation front with CPI (rural and urban combined) rising at 4.8 per cent per annum, well within the tolerance limits of RBI’s targeted inflation band and also much lower than 7.8 per cent during the first seven years of Singh’s government. But Modi had the advantage of low global crude prices. However, CPI inflation has now flared up to 6.3 per cent, thanks to the rise in fuel prices. Petrol is now is now retailing at above Rs100 a litre, an unprecedented hike.

One area in which the Modi government has performed poorly is agri-exports. In 2013-14, the last year of the UPA government, agri-exports had crossed $43 billion, while during all the seven years of the Modi government agri-exports remained below this mark of $43 billion. Sluggish agri-exports with rising output have also put downward pressure on food prices. It helped contain CPI inflation, but subdued farmers’ incomes. Given this, the dream of doubling farmers’ real incomes by 2022-23 may remain just a pipe dream.

Also, at the macro level, the Modi government fares quite well with forex reserves rising from $313 billion on 23 May 2014 to $593 billion on 21 May 2021, thanks to its policies of liberalizing FDI. Foreign exchange reserves provide resilience to the economy against any external shocks.

On the social front, the UPA’s MGNREGA, once debunked by Modi, has stood out as a valuable safety net. The Modi regime has yet to come up with a programme of similar import to tackle unemployment caused by economic disruption.