-

Prakash: we have vast knowledge of electric loco production

The committee which the railways had formed to investigate the possibility of establishing a locomotive manufacturing unit and consider its economic viability, submitted its report in the 1940s. The initial project, at Chandmari, a place near Kanchrapara, in West Bengal, could not mature due to partition, which inevitably necessitated a change of site. The issue of setting up a loco building unit was under the active consideration of the central legislature in December 1947. The Railway Board decided to locate the factory at Chittaranjan, near Mihijam.

In January 1948, a survey of the proposed area commenced. The rocky soil was an advantage in erecting foundations for heavy structural work and the undulating terrain solved the problem of drainage for the township while the schemes of the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC), which envisaged hydroelectric and thermal power stations in the vicinity, assured adequate power availability for the enterprise. The workshop and the colony are spread over an area of over seven square miles.

The locomotive works, originally called ‘Loco Building Works’, were initially established for the production of 120 average sized steam locomotives with a capacity to manufacture 50 spare boilers. Production of steam locos commenced on India’s Republic day in 1950. The first President of India, Dr Rajendra Prasad, dedicated the first steam locomotive to the nation on 1 November 1950, and on the same day the Loco Building factory was rechristened and named after the great patriot, Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das – son of the soil – and became Chittaranjan Locomotive Works.

Apart from meeting the growing and varied needs of Indian Railways, CLW has been, right from inception, adopting modern designs and upgrading technology, gradually enhancing the haulage capacities and speeds of locomotives. The average speed in its passenger locos has increased from 140 to 160 kph in the last two years through innovative modifications.

CLW witnessed the transformation of the locomotive engine from steam to diesel and electric, at present, over the last 70 years. The last steam locomotive rolled out from CLW in 1972. By then it had started diesel locomotive engine production which continued till 1993. It then completely switched over to the production of electric locomotive and the maintenance spares required by Zonal railways. The West Bengal based loco maker has so far produced 2,351 steam, 842 diesel and 7,301 electric locomotive engines of different classes and categories. Almost 10,500 engines have rolled out from the company in the last 70 years to fulfil the requirements of Indian Railways.

In-house production

Backward integration, over the years, has reinforced CLW’s operations. It produces several components in-house for making locomotives. “Our advantage is that we produce 70 per cent of the loco value in-house,” says Mishra.

-

Capacity utilisation is more than double

The steel foundry of CLW meets the requirements of different casting products, like flexi coil bogie, flexi coil bolster ballast block, wheeling unit, loco coupler, etc.

The cumulative production of three-phase traction motors – 2,330 of them – is 35 per cent higher than the previous year. Using three-phase locomotive technology from Bombardier Transportation, Switzerland, CLW has geared up to manufacture 1,000 HP and 1,500 HP state-of-the-art three-phase traction motors for freight (WAG-9) and passenger (WAP-5 & WAP-7) locomotives. Adopting the latest technologies in traction field & locomotive production, CLW always endeavours to remain abreast and preeminent in this field.

CLW also has in-house manufacturing facilities of other electrical power and control equipment, ie smoothing reactor, inductive shunt, master controller, traction braking switch, electro-pneumatic (EP) contactors and reversers. There is a reduction of import content in electric loco at CLW from 4.36 per cent (2016-17) to 2.54 per cent (2018-19).

The manufacture of electric locos is a complex process. There are 65 workshops and it takes 75 days to assemble the 3,500 components that go into making a locomotive. The cost of a loco varies from Rs10 to Rs12 crore, depending on the type. CLW’s strength has been its ability to play long term and implement sustainability in business operations. “In the Indian context, we have all the knowledge to meet any requirement in loco production. Our strength is in our design and new developments. Innovation is a continuous process for us,” claims Ram Prakash, principal chief electrical engineer. He is in charge of production. CLW has a pool of some of the finest engineers in the country.

CLW is a veteran with vast knowledge in making electric locos. Even three years ago, the company was the only electric loco producer in India. Later, DLW and DMW also became electric loco players when Indian Railways stopped diesel loco manufacturing and shifted them to electric loco following the railway ministry’s announcement of complete electrification in the country. The demand for electric locos is on the rise and CLW will continue to lead the industry.

Being the big brother in electric loco manufacturing CLW is now handholding DLW for making the transition to electric locos. “We supply material, train the workforce and control DLW’s manufacturing parameters,” says Mishra. DLW, situated in the Prime Minister’s constituency, has a workforce of over 5,500.

CLW’s expert team in design and development works relentlessly for improvement. Its 9,000 HP freight loco WAG 9HH with advanced features successfully cleared its trial this year. “Our engine has passed the oscillation and EBD (Emergency Braking Distance) trial conducted by the Research Design and Standard Organisation (RDSO) at a speed of 100 kph,” says Prakash. The new electric loco is expected to haul 58 box wagons and will increased the haulage capacity of Indian Railways by almost 50 per cent. The loco will be used for the DFCC (Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation) project run by the Ministry of Railways.

-

Our strength is in our design and new developments. Innovation is a continuous process for us

Similarly, two WAP-5 locomotives have been modified with aerodynamic reprofiling. The profiles of both cabs are optimised to meet requirement of operation in a push-pull configuration as well as at higher speed and are likely to be despatched soon.

A senior manager at CLW, speaking on condition of anonymity, says CLW should now focus more on automation rather than contend with production numbers.

CLW is gradually investing in its plant infrastructure to ramp up production capacity. “The government had sanctioned R134 crore for the modernisation and augmentation of an additional 75 electric locomotives,” says principal financial advisor Ravij Seth.

Large manpower

Incidentally, Indian Railways has formed a joint venture with Alstom SA of France for the production of high-power freight locos and it set up Madhepura Electric Locomotive Private Limited in Bihar in 2017. The Railways own 26 per cent stake in the JV. This is part of the first FDI in Indian Railways. The company will produce 800 electric locos of 12,000 HP within a span of 11 years for the freight corridor. The first loco rolled out from its plant three years later, in May this year.

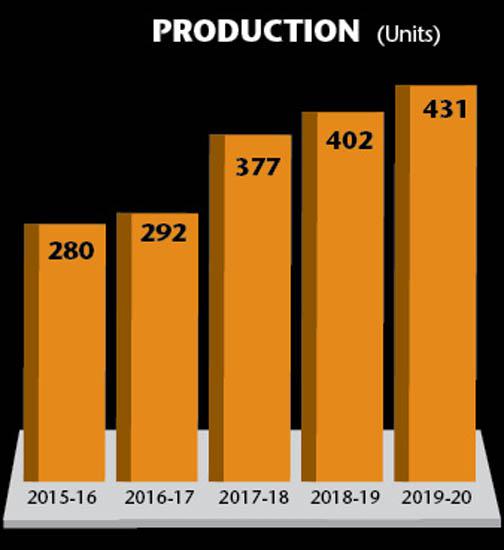

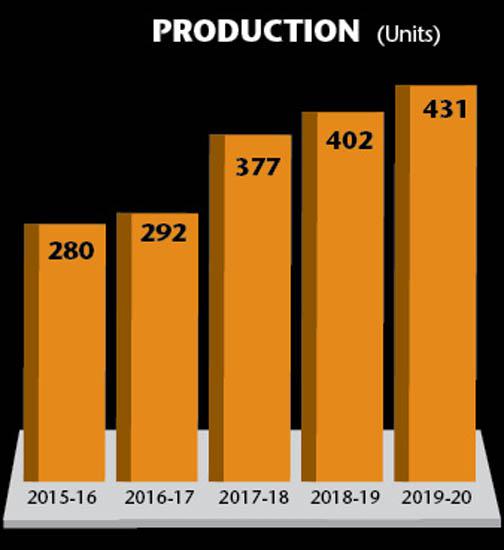

CLW also has an inheritance of large manpower. It needs to be the right size. The company has frozen recruitment for the last few years. “Unlike DLW, we are hardly dependent on outsourced components. Most of them we manufacture in-house, including bogies, traction motors, also foundry operations and they are labour-intensive,” argues Mishra who has 35 years experience in Indian Railways. When he took over as general manager, CLW in September 2018, he had set a target to increase production by 18 per cent. It was achieved without much resistance. “The productivity of our workforce has increased enviably. Three years back with the same or more workforce we produced 260-plus,” explains Mishra.

In 2006, the electric assembly and ancillary unit of CLW was set up at Dankuni in West Bengal to augment the production of freight locomotives. Since inception, it has been producing WAG-9 locos. The Dankuni unit produces 60 locos a year with 450 people. The company is now planning to manufacture 10,000 HP locos with some collaboration. “This is still at a nascent stage. We are working on the feasibility. We may consider importing the technology for the project,” says Mishra.

-

The loco maker was closed for 49 days due to the Covid pandemic. Production was badly affected. Once production commenced, CLW have maintained all safety measures in the unit. “At present we have reached last year’s average level of production of 30 locos per month. Now we are determined to make it 40 locos per month to cover the loss due to the lockdown,” Mishra says.

The company has streamlined the vendor supply chain. It used to monitor this periodically, but now it does so on a regular basis. It now keeps inventory for one-and-a-half months. Kolkata-based Shiva Engineering Works is one of the vendors of CLW for the supply of the finished electric locomotive shell. The company has been associated with CLW since 2008.

“CLW has very stringent quality measure which also helped us to improve our production parameters. Their digitised tendering system brought more transparency into procurement. Payment is also quick,” says Abhishek Modi, vice president, Shiva Engineering Works. The company is also one of the oldest suppliers for the defence industry (since 1960).

CLW will continue to remain the market leader in electric locomotives, with a healthy order book, says Seth. The management expects that in the next four to five years, production will easily reach 500 units. The Indian Railways has been mulling corporatizing its seven production units, including CLW, into a single entity called Indian Railways Rolling Stock Company. Railway unions have opposed the idea. But if the government is allowed to go ahead with the plan, then the challenge for CLW would be to accommodate the changes in the ecosystem.