-

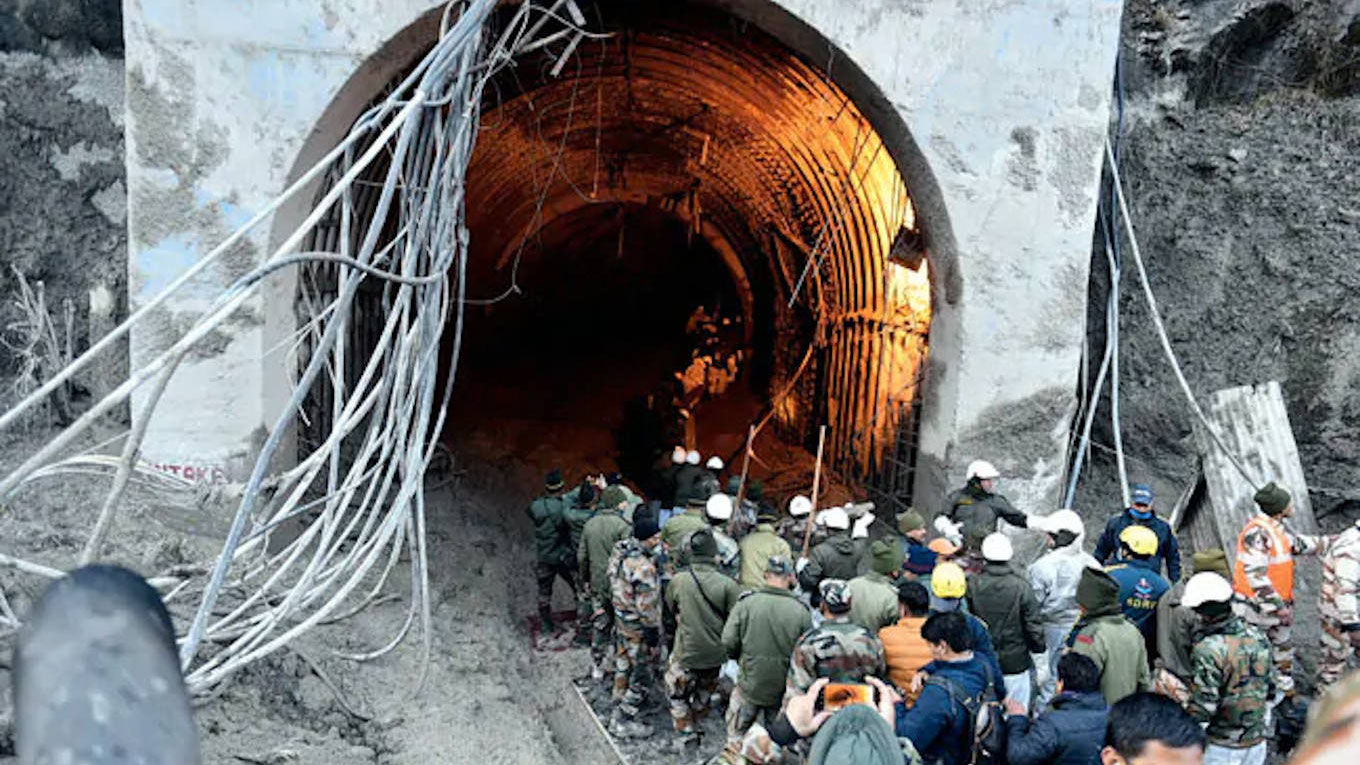

Rescue workers cutting a passage to connect to the Tapovan tunnel

Fragile Himalayan ecosystem

Uttarakhand lies on the southern slope of the Himalaya range, its climate and vegetation varying greatly with elevation – from ice, bare rock and glaciers at the highest elevations as, at the 7,816 m high Nanda Devi, India’s second highest mountain, after Kangchenjunga, and the 23rd highest peak in the world, to sub-tropical pine forests below 1,500 m. Glaciers have been melting rapidly in the Himalayas, as across the world, because of global warming.

Uttarakhand alone has 968 glaciers with a cumulative volume of 277.5 km³ and straddling a total 2,857 sq km. Gangotri, at 30.2 km, the largest among them and located at 7,100 m above sea level, alone has an estimated volume of over 27 km³. But its rate of retreat over the last three decades has been more than three times that during the preceding 200 years. Himalayan glaciers are retreating faster than the world average, this situation only aggravating with temperatures in the Indian sub-continent predicted to rise appreciably in future. Their rapid reduction is affecting stream flows, hydrology and biodiversity downstream.

One study determines that many of the glaciers in Uttarakhand have lost over a tenth of their mass in less than three decades, Uttari Nanda Devi glacier having receded the most, by 7.7 per cent. The state besides has over 1,200 big and small lakes in the higher reaches. When glaciers shrink on account of rising temperatures, their snow melts but the debris remains, and often this debris aids in the formation of lakes.

Two prominent rivers of Hinduism originate in the glaciers of Uttarakhand, the Ganges at Gangotri and the Yamuna at Yamunotri. They are fed by myriad lakes, glacial melts and streams, and the two, along with the hallowed temple towns of Badrinath (dedicated to Vishnu) and Kedarnath (dedicated to Shiva), form the char dham, one of the holiest pilgrimages for the Hindus.

It is these glacial rivers that eventually drain into the 2.5 million km² Indo-Gangetic Plain, which spans the northern regions of the Indian sub-continent encompassing most of northern and eastern India, eastern Pakistan, most of Bangladesh and the southern plains – Terai – of Nepal. These great rivers, together with the glaciers and snow melt, nurture this vastness, assuring food security to over 900 million people. The Himalayan ecosystem also provides habitat for varied flora and fauna, including rare plants and herbs that have healing properties.

The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) maintains, however, that more than 85 per cent of Uttarakhand’s districts are hotspots of extreme floods and associated weather events, the frequency and intensity of extreme flooding having increased fourfold since 1970. Landslides, cloud bursts, glacial lake bursts and related natural occurrences too have quadrupled during this period, causing massive loss and damage.

-

With much focus on the tunnel, villagers rue the scant attention given to rescuing missing locals

Geologists of Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University surveying the Rishiganga area following the 7 February devastation, have, in fact, identified a water body having formed near the Rishiganga river that can unleash floods again. They explained that the Rishiganga started rising when part of it got dammed by cascading mud and rock, compelling a temporary halt to rescue operations and an alert being issued to villagers in the area. The rising waters started pounding the lake and the geologists fear the lake may breach and flood the Rishiganga in an event called Landslide Lake Outburst Flood (LLOF), sabotaging the rescue effort and compounding the calamity.

The 53,483 km2 land-locked Uttarakhand, which shares its international borders with China’s Tibet Autonomous Region to the north and Nepal in the east, has a population nearing 12 million and is often referred to as ‘Devbhumi’, Hindi for ‘land of the gods’, due to its multitudes of Hindu shrines and pilgrimage centres.

Intent on transcending the pilgrimage-tourism image of Uttarakhand, past governments set the state on the path of ‘development’ and ‘industrialisation’, spring-boarding the 86 per cent mountainous and 65 per cent forested Uttarakhand into one of India’s fastest growing states and a key investment destination for manufacturing and infrastructure. Industry-friendly and incentive-laden approaches catalysed the development of industrial infrastructure, including integrated industrial estates and sector parks.

Tampering with river flow

Its abundant water reserves deemed hugely favourable for hydro-power, Uttarakhand was envisaged as an ‘energy state’ by harnessing its then projected hydel potential of over 25,000 MW. Subsequent planning far overshot that, with the state, at the time of the 2013 disaster, having constructed 130 micro-mini to large HEPs with a total installed capacity of 6,916 MW, with 450 more, of a combined 27,039 MW, in various stages of construction. Barraging the rivers to power industry downstream can, in the long run, drain the Indo-Gangetic Plain, putting food security at risk and threatening famine for millions.

All of Uttarakhand lies in high seismic risk zone, its topography ranging from Zone IV (severe intensity zone) to Zone V (very severe intensity zone). The building of dams, gargantuan power plants, power lines and support facilities, blasting with explosives, dredging of riverbeds for sand, and clear-felling forests for new roads in such a susceptible region are warned to have long-term consequences. These actions minimise flows, leading to loss of river integrity, change river courses, erode escarpments, disrupt fish migration, and endanger aquatic biota and diversity. Construction of multiple projects moreover fragments river length, as for instance half the 205-km length of the Bhagirathi.

-

Paramilitary personnel have bolstered the rescue efforts

Residents of the local Raini village had in 2019 petitioned the Uttarakhand High Court on the environmental impact of the Rishiganga HEP. The court had reportedly asked the state government to form a team to inspect the issues raised and stayed blasting in the project area till further orders. Other villagers have similarly contested other projects, underscoring the fact that they are neither consulted when authorities encroach upon their lands, nor do they find such inroads beneficial to them. Indeed, they see a threat to their environs from these intrusions.

Past reports by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India had pointed to the ‘poor quality pre-feasibility studies’ that had assessed the desirability of dams in particular areas of this Himalayan region, and decried the absence of punitive action against developers who violated guidelines, executed projects shoddily, and showed little concern for environment and safety. According to the

CAG, river beds frequently ran dry owing to unrestrained work methods, there was a general disregard for afforestation, and there was little government support for relief and rehabilitation of locals displaced by the projects.

An expert body set up by the Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF) on the directions of the Supreme Court, following the 2013 calamity, was tasked to assess whether hydropower projects have contributed to environmental degradation in the region, and to the biodiversity of the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi river basins.

It was reported that such construction severely affected river water quality due to unscientific and unlawful dumping of muck from road and tunnel construction. Poor official monitoring was also a factor. But the most serious impact on biodiversity was the loss of the riverine ecosystem. The destruction did not end upon completion of the construction, as repeated raising and lowering of water levels induced landslides along the river courses.

What is now required is a return of this once pristine mountain state to a pilgrimage and tourism economy, where local arts and culture are encouraged and Himalayan herbs can flourish.