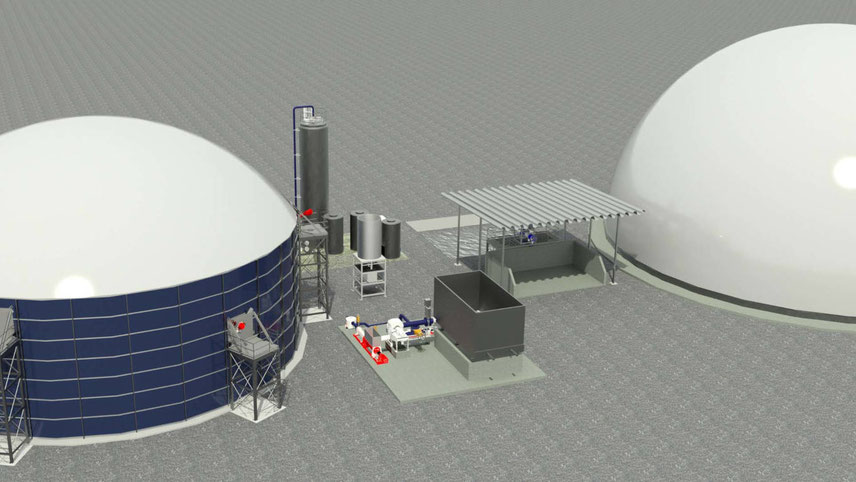

In January, there were reports that the Myanmar military, in hot pursuit of pro-democracy forces, had launched an airstrike on a prominent training camp close to the Indian border, with jets dropping at least two bombs inside Indian territory. India’s muted reaction has only confirmed its deep foreign policy dilemma on how to handle Myanmar two years after the military coup there. The problem is compounded by the fact that thousands of refugees from the Chin state in Myanmar, which abuts the border, have poured into Mizoram and Manipur. This, of course, is in addition to the Rohingya refugees who keep on trickling into India. Two years ago, the National League for Democracy had scored a handsome victory in the national elections, but the army generals, fearing an erosion of their clout, staged the coup alleging rigging by Aung San Suu Kyi’s party. Pro-democracy forces have since then challenged the military, turning swathes of the country into no-go areas for the army. A number of armed ethnic organisations fighting the state for autonomy have joined these forces, posing a tough challenge to the military junta. Hitherto, India’s policy was to do business with the military junta for its help in securing the north-eastern borders and tracking down the insurgent groups that operate on the region. It kept a channel of communication open with the pro-democracy forces, offering them, as a retired diplomat put it, ‘tea and sympathy’. However, the present leadership of the military junta, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, has failed to bring the country under control after the coup. Not taking sides India has another reason for not doing business with the military junta: as the current chair of G20, it does not want to be seen as a country siding with a regime, which suppresses democratic rights across the border. The US has already announced sanctions against the top Myanmar generals. There has been widespread condemnation of the Tatmadaw with calls for international censure of human rights violations inside Myanmar. New Delhi has sought not to take sides on the matter and has, along with Russia and China, abstained from a UN Security Council resolution criticising Myanmar’s military regime. It has instead called for ‘quiet, patient and constructive’ diplomacy with the junta. One of the reasons India is exercising and advocating caution is the fear that any overkill in condemnation will drive the military junta into the waiting arms of China. The impasse has also put a question mark on the inauguration of the Sittwe port, developed as a part of the Kaladan regional connectivity project. Sarbananda Sonowal, Union minister for ports, shipping and waterways, had, in January, announced that the port project is ready for operation. The objective of the project was to provide alternative access to India’s landlocked north-eastern region via the Kaladan river. Indeed, the Kaladan multi-modal project was the most significant investment India had made in Myanmar. It includes a waterway component of 158 km on the river Kaladan, from Sittwe to Paletwa, and a road component of 109 km from Paletwa to Zorinpui, on the India-Myanmar border in Mizoram. Once the port is made operational through a private operator, Indian goods can be taken via the Aizawl-Zorinpui-Palletwa axis to Kaladan river, and then transferred to Sittwe port. It is crucial to India’s plans for the landlocked north-eastern states to access the Bay of Bengal through Mizoram and to provide alternative connectivity to Kolkata without having to use the circuitous Siliguri corridor.

-

Sittwe port: providing an alternative access to north-eastern regions