-

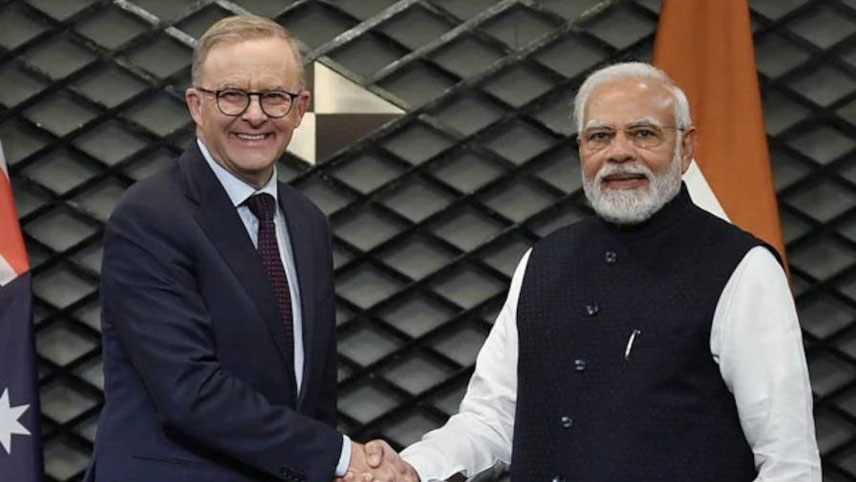

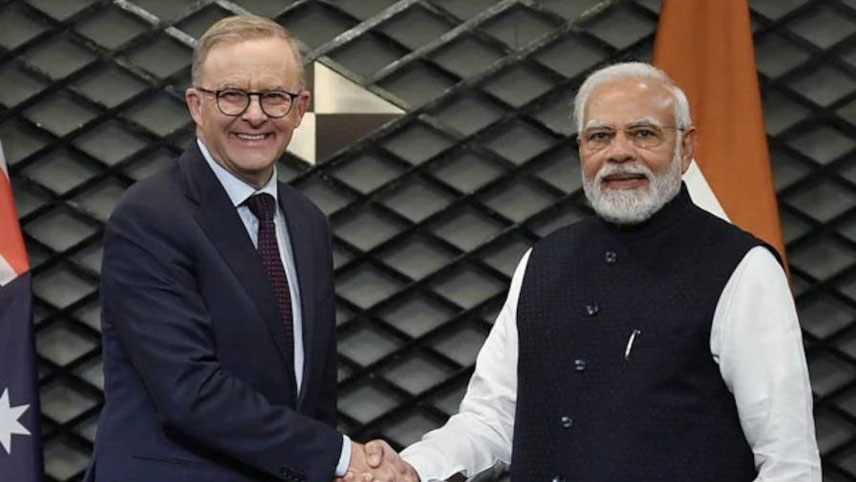

Albanese with Modi: renewing the commitment?

While India will need to rely on imports for these technologies over the next two decades, the study advocates that further work must be done to better utilise the available minerals within the country for its longer-term needs. As such, India can be better prepared for the next stage of green technology utilisation by laying the groundwork for exploring and mining.

For this, India will also need to undertake serious research and build a policy framework for becoming self-reliant in clean energy and high-tech equipment by acting quickly on the exploration and mining of critical minerals and setting up investments in the downstream value chains of requisite manufacturing equipment at home.

Rare earths have posed a particular headache for Western countries because of China's dominance over the supply chain, particularly the processing stage of production. The only operating rare earths mine in the US, for example, has been shipping its concentrate to China for refining.

Mining sector reforms

In India, reforms in mining and downstream sectors of critical minerals can boost not only domestic high-tech manufacturing, but also its green future goals. But there is the question of investment. Rare earths mining and extraction processes are capital intensive. Also, the process consumes large amounts of energy, and releases toxic by-products. Finally, processed minerals usually take the form of a rare earth oxide (REO), which then needs to be converted into a pure metal before it can be used to make anything.

Till a system is put in place, the country must also focus on securing supply chains for critical minerals and acquiring foreign mineral assets to ensure a continuous supply. “The import risks of critical minerals may be reduced by developing resilient supply chains, signing trade agreements, and acquiring mining assets abroad,” the CSEP paper notes.

India has thus taken the route to collaborate commercially with other like-minded countries to meet its requirements. In their first official meeting, as part of the cooperation in critical and emerging technologies, the four-nation Quad group committed to improve resilience in the rare earth industry to reduce dependency on China due to its geostrategic importance.

All Quad countries have a common list of requirements, which mostly include graphite, lithium and cobalt, which are used for making EV batteries -- rare earths that are used for making magnets and silicon, which is a key mineral for making computer chips and solar panels. Aerospace, communications and defence industries also rely on several such minerals as they are used in manufacturing fighter jets, drones, radio sets and other critical equipment.

Ministerial visit

Critical minerals were on the top of the agenda of Pralhad Joshi, minister, Union coal & mines, during his recent visit to Australia, which has the world’s biggest reserves. Australia’s Lynas Corporation is second largest producer of rare earths after China and can play a key role in reducing rare earth reliance on China.

Australia is also investing in Malaysia’s $800 million rare earth processing plant, which can become the world’s leading processing facility and a challenge to Chinese monopoly, if it becomes operational. Thus, critical minerals have emerged as the centerpiece of India-Australian collaboration.

-

Joshi with King: strengthening India-Australia partnership

Australia is in prime position to assist India to achieve its clean energy goals through the supply lithium and other critical minerals. It has a range of development-ready critical minerals projects that, if quickly scaled up, could support India’s ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-reliant India)’ and ‘Make in India’ manufacturing plans.

The availability of processed critical minerals will also help India meet its growing clean energy requirements and targets, which include 50 per cent of its energy requirements through renewable energy and the rapid expansion of electric mobility to 30 per cent of total vehicles by 2030.

Joshi’s visit was aimed at strengthening India-Australia partnership in the field of projects and supply chains. As part of his six-day tour, he met his counterpart, Madeleine King, Resources and Northern Minister, after which Australia confirmed that it would “commit A$5.8 million to the three-year India-Australia Critical Minerals Investment Partnership”.

The AI Critical Minerals Investment Partnership flows from the MoU signed by Australia’s Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources and India’s Ministry for mines in 2020 on increasing trade, investment and research and development in critical minerals between the two countries.

Pursuant to this, another MoU was signed between Khanij Bidesh India Limited (KABIL), a joint venture between three PSUs under the Union mines ministry -- NALCO, HCL and MECL -- and Critical Minerals Facilitation Office (CMFO) of Australia. The MoU includes joint due diligence in lithium and cobalt mineral assets of Australia. “Once the due diligence is completed and potential projects are identified, we will explore investment opportunities through different methods as envisaged in the MoU," Joshi said. The initial funding is to be shared equally by both countries.

Legacy Iron Ore

The mines minister also held a review meeting with officials of Legacy Iron Ore, a Perth-based exploration company with NDMC Ltd, India’s largest iron ore company with a market cap of Rs30,595 crore, holding 90 per cent shares. Legacy is exploring and developing mineral projects in Western Australia. The principal commodities are iron ore, manganese, gold, and base metals.

One of the showpiece projects of Legacy is Mount Bevan, a joint venture between Legacy and Hawthorn Resources Limited whereby Legacy will earn a 60 per cent interest in the project by expending a minimum of $3.5 million to develop the project to a pre-feasibility status. Mt Bevan is considered to hold excellent potential for the definition of substantial hematite and magnetite iron resources that are located close to existing road, rail and port facilities.

“Australia has the resources to help India fulfill its ambitions to lower emissions and meet growing demand for critical minerals to help India’s space and defence industries, and the manufacture of solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles,” King affirmed. “Australia welcomes India’s strong interest and support for a bilateral partnership which will help advance critical minerals projects in Australia while diversifying global supply chains”.

According to a Modi government spokesman, “The India-Australia critical minerals investment partnership envisages joint investment for viable lithium and cobalt projects in Australia, which is critical for India’s transition towards clean energy ambitions.” As India is among the fastest growing economies in the world, there is huge scope for collaboration in the mineral sector, Joshi adds. Technology transfer, knowledge-sharing and investment in critical minerals like lithium and cobalt are strategic to achieving these ambitions.

-

Rajnath Singh, S. Jaishankar, Antony Blinken and Llyod Austin at the fourth US-India 2+2 dialogue

However, while Australia has the technological expertise necessary for extraction and mining of rare earths and Australian companies can facilitate export of services and technologies used for processing, refining, recovering, and recycling of REEs, they want their share of the pie. These companies want exploration rights to India’s REE reserves, so that they have the economies of scale for offtake arrangements and a robust pipeline of manufacturing-led commercial innovation opportunities.

India-US collaboration

It isn’t just the Australians that India is wooing. During the fourth US-India 2+2 dialogue between S. Jaishankar, Rajnath Singh and Antony Blinken and Llyod Austin in April, it was felt that of all these areas of discussion enhancing India-US partnership, critical minerals and emerging technology are the major need of the hour for their green future goals.

Energy security and shift to a green future have been at the core of the India-US strategic partnership, after their defence and trade relations. The green future partnership began taking shape since the India-US energy dialogue in 2005, which set up five working groups focusing on emerging technologies and renewable energy, besides oil, gas, coal, energy efficiency, and civil nuclear.

Though the two countries have different resource endowments and capabilities, their green future has potential to build a more developed, resilient and sustainable clean energy supply chain. However, a difference in perceptions came to the fore after the Donald Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, while India announced its continued commitment the same year.

Climate change imperatives

Now, with the US, under President Joe Biden, rejoining the Paris agreement in 2021 and organising the virtual summit on Climate Summary of Proceedings convened by 40 world leaders, things are again looking up. The summit involved the US-India joint statement launching the ‘Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership’. As part of this partnership, the US set its target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, and India shared its objective to install 450 GW of renewable energy by 2030.

The two countries are now of the view that in the current scenario of increasing supply chain vulnerabilities and global semiconductor crisis, the world is looking for alternatives and initiatives in the form of resilience. Both have become increasingly active in their path to secure a supply chain of critical minerals and elements in the past decade, recently enacting laws prioritising the domestic manufacturing capacity that requires secured access to critical elements like the US Compete Act and the Indian Semiconductor Mission.

Critical minerals are already developing as a new base for multilateral collaboration, as seen in the “Quad critical and Emerging Technology Working group”, which aims to develop supply resilience among Quad members -- India, the US, Japan and Australia.

The focus on critical minerals supply chain began primarily after the China-Japan dispute over the Senkaku-Diaoyu in 2010, which was followed by a rare-earth embargo imposed by China. This was taken as a serious threat by the US, European Union and Japan because they were the major importers of rare earths. This made the US House of Representatives pass HR 761 that declared rare earths as essential for economic growth and national security.

-

Dhar: India-Australia bilateral trade will double in five years

The US critical minerals vulnerability got more acute with the US-China trade war (2018), when China retaliated against US-imposed tariffs by restricting the export of rare earths and other critical minerals to China. The Covid-19 pandemic caused global semiconductor shortage added to the growing global critical minerals vulnerability. There have been multiple strategic initiatives announced by the US to develop its domestic critical minerals mining, such as the Strategy to Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals (2017), Onshoring Rare Earth (ORE) Act (2020), US Compete Act (2022), and others.

India’s role

India, as a reservoir of major critical and non-fuel minerals, can be a sustainable source. Add to that the rich deposit of monazite on our beach sands. In the growing US-led initiatives to reduce reliance on Chinese raw materials and critical minerals, an India-US strategic partnership can help to enhance the supply chain resilience. However, reforms in the Indian mining and downstream sector of critical minerals are imperative to boost the output.

Till that happens, India has to turn to Australia which has reserves of at least 21 of the 49 critical minerals identified by the Indian government. Australia, for instance, has the potential to be one of the top suppliers of cobalt and zircon to India, being in the top 3 for global production of these minerals. Australia also has reserves to supply many other critical minerals like antimony, lithium, rare earth elements and tantalum.

The recently signed Australia-India Critical Minerals Investment Partnership will support further Indian investment in Australian critical minerals projects. Australia has a range of development-ready critical minerals projects that, if quickly scaled up, could support the ‘Make in India’ manufacturing plans.

Both countries are expecting that the India-Australia Economic Co-operation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) will support further growth and investment in Australia’s world-leading critical minerals and resources sectors. The pact will promote growth in Australian minerals exports to India by eliminating and reducing customs duties on key products, improving access to a growing and diversified market for the Australian critical minerals sector.

As a priority strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific, and Australia's fifth largest energy and resources market, India is positioning itself as a major investor in Australian resources with significant (and growing) demand for critical minerals products. Australian firms are also well-placed to meet India's growing demand for mining equipment, technology and services and have a competitive edge in mining consultancy; exploration technologies; mining software; processing components and systems; environmental and mineral quality technologies and safety equipment; and mining education and skills.

Change in Canberra

That is why the recent political change in Canberra was being closely assessed in diplomatic and investment circles in India. At one stage, it was felt that the defeat of Australia's conservative Prime Minister Scott Morrison and the victory of the centre-left Labor dispensation led by Anthony Albanese could put pressure on the Modi government to recalibrate the New Delhi-Canberra equation. The result of the Australian federal election was being seen as a stinging rebuke of the inaction of Morison’s Liberal-National coalition on climate change, among other pressing domestic issues.

-

The India-Australia critical minerals investment partnership envisages joint investment for viable lithium and cobalt projects in Australia, which is critical for India’s transition towards clean energy ambitions

Morrison and Modi had held up bilateral ties as a factor of stability in the Indo-Pacific, ramping up collaboration in defence, critical minerals and trade. India and Australia, both members of the Quad, upgraded ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2020, holding annual institutionalised summits of the heads of government like those with Japan and Russia.

The oft-cited political canon is that the Australian Liberal party has given more attention to India, while the Labor party has traditionally been seen as friendlier towards China in the past. The exception to this conventional wisdom is the Julia Gillard government, which pushed to remove obstacles to the sale of uranium to India in 2011. Incidentally and ironically, Albanese was among the Labour leaders opposed to the move, citing nuclear proliferation concerns and the Fukushima nuclear disaster which took place then.

The only two Labour Prime Ministers who connected with India were Bob Hawke and Gilliard. Of particular failure in building a closer relationship with India was Paul Keating who as PM all but ignored India. Worse still, this was at a time in the early 1990s when India was opening up its international trade and foreign investment opportunities. Labour’s closeness to China, especially under Kevin Rudd, has also been well-documented.

However, in his first foreign policy foray at the Quad summit in Tokyo, Albanese declared that China must remove its trade sanctions on Australian products to have any chance of improving relations between the two countries, thereby opening a door of sorts. In the past, Albanese had also said he will be ‘completely consistent’ with the outgoing Morrison's administration on Chinese strategic competition in the region.

Bipartisan backing of ECTA

The good thing for New Delhi is that the inking of the India-Australia ECTA received bipartisan support in Australia as it was widely perceived that the ECTA could help in broadening and deepening India-Australia trade. Australia has agreed to eliminate tariffs on 98per cent of its tariff lines when the agreement enters into force.

Tariffs will be removed on the remaining lines within five years. In contrast, India will eliminate tariffs on 69 per cent of its tariff lines, while almost 30 per cent are in the exclusion list. Through these commitments, India will reduce its average tariff rate on Australian imports from 14 per cent to about 6 per cent when the ECTA is fully implemented. These commitments augur well for the adoption of the full-fledged trade agreement, Comprehensive Economic Co-operation Agreement (CECA) in the near future.

Biswajit Dhar, professor, Centre for Economic Studies & Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, points out that India expects its bilateral trade with Australia to double within the next five years.

-

Lithium mine in Australia: Australia has reserves of at least 21 of the 49 critical minerals identified by the Indian government

This could happen if New Delhi is able to expand its exports of pharmaceuticals and textiles and garments, areas in which it has a competitive edge, and in electronics products like mobile phones, which have lately seen robust increase exports from India. Trade in the pharmaceutical sector could benefit from the decision taken as a part of the ECTA that drug regulators in both countries, the Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia and India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, will work in close co-ordination.

In the services sector, he points out, Australia has responded positively to one of India’s main areas of interest, movement of natural persons under Mode 4, by allowing several categories of professionals to access its market in 26 sectors. However, Australia’s offers do not cover sectors like health and education in which India has perceived strengths.

Both sides are hoping that with the CECA in place by the end of 2022 , bilateral trade will increase from the current estimates of $27 billion to about $50 billion over the next five years, creating millions of jobs.

Albanese had his first face-to-face meeting with Modi in Tokyo, during the sidelines of meeting the Quad, where the two leaders also reviewed the India-Australia ECTA and exchange views on regional and global developments, including Ukraine. Indian officials were surprised by the awareness that Albanese showed about India, who had travelled across the country as a backpacker in 1991, and later as head of a parliamentary delegation in 2018.

In his election campaign too, he had ‘committed to deepen economic, strategic and people-to-people links’ between the two countries. Following the recent bilateral movement on critical materials, it is obvious that the momentum gained by bilateral ties during Morrison’s period has stood the test of time.

-

Australia is in prime position to assist India to achieve its clean energy goals through the supply lithium and other critical minerals

Assessing the criticality

• India has resources of nickel, cobalt, molybdenum and heavy rare earth elements, but further exploration is needed to evaluate the quantities of their reserves;

• India does not produce some of the key minerals for making photo-voltaic cells, such as silicon, silver, indium, arsenic, gallium, germanium, and tellurium;

• India also does not produce key minerals needed to make EV batteries, including lithium and cobalt;

• Lithium, strontium and niobium have relatively high economic importance for India, and heavy rare earth elements, niobium and silicon have relatively high supply risks;

• Titanium, lead, and manganese face relatively low levels of supply risks;

• Nine minerals have relatively low economic importance: titanium, graphite, silver, vanadium, zinc, lead, cerium, neodymium, and indium; and

• Most minerals have some degree of substitutability, except for niobium and silver, for which there are no good substitutes.

Source: CSEP working paper