-

Attendance

China and Russia are the first and fourth largest global polluters, responsible for a combined 32 per cent of annual emission. The failure of Xi and Putin to attend dramatically reduces significant progress being made on key initiatives.

Participation of national leaders is de rigueur for events like COP26, especially with years of high expectations. The participation and statements by these leaders sets the tone for the ambition of negotiations and is symbolic of the country’s commitment to global collaboration.

Covid

After a year-and-a-half of the global pandemic curbing economic activity and ravaging populations, participants are attending COP with vastly different experiences.

Participants from well-vaccinated, wealthy countries are attending with a sense of triumph over Covid. The global order has provided the ability for wealthy economies to support citizens through lockdowns, faster economic recovery and disproportional access to vaccines and health care.

Many poor and developing countries still do not have enough access to vaccines and healthcare. The economic strain is increasing as global prices rise and supply chains break down. These countries have less ability to send representatives, even with the UK providing quarantine lodging and vaccines on an as needed basis.

Participants from many wealthy countries believe that Covid demonstrated that if we all come together and sacrifice a bit, we can overcome. Conversely, participants from many developing economies see Covid as not dissimilar from climate change. The failure of the international community to facilitate access to vaccines and healthcare resources is not unlike the failure of rich countries to meet modest climate finance pledges while demanding developing countries make more robust commitments while often more vulnerable to extreme weather events.

Economic Recovery

While it is a mistake to consider economic growth as counter to climate action, Covid disrupted supply chains and other systems that are proving difficult to restart. As countries strive for economic recovery, demand for energy has increased dramatically, thereby increasing reliance on fossil fuel-based energy.

Excess demand and supply chain disruptions including lack of labour and extreme weather events, have resulted in multi-year highs of natural gas, oil, and coal prices, thus diverting resources that might have otherwise supported climate action.

Energy shortages in China, the UK, Europe not only raise the question of grid stability while transitioning to renewables but can also influence the ability of countries to commit to revised NDCs that might have seemed natural a year back.

Domestic Politics

The return of the US to the Paris agreement was expected to dramatically increase its NDCs and mobilisation of funds for developing countries. While both have improved under the Biden Administration, polarisation and political infighting have prevented the country from reaching the levels that had been expected earlier in the administration.

Similarly, climate activists from Brazil eagerly seek greater support for rainforest protection. The government, under Prime Minister Jair Bolsonaro has committed to net-zero by 2050. However, deforestation under his leadership has increased and in 2019, the government objected to the standard accounting of methane to CO2E equivalents.

-

Many wealthy countries believe that Covid demonstrated that if we all come together and sacrifice a bit, we can overcome

Geopolitical Issues: China

As the world’s largest polluter and second largest economy, China’s commitments at COP26 are undoubtedly important. Xi is not attending. His absence, paired with increased tensions with the global community and China’s below expectation revised NDCs, do not bode well for other negotiations.

Tensions over Taiwan, China’s shared border with India, and trade have already strained relationships with neighbours and the larger global community. While this doesn’t lead to immediate climate impacts it certainly increases tensions in climate negotiations.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, on the other hand, has been characterised by both predatory lending practices and a reliance on fossil fuel-based energy. China has investments in coal mines and fossil fuel power generation around the world. There is some speculation China will pledge to halt new fossil fuel-based investments as part of this initiative.

Silver Linings: India

India has often been the leader for developing countries, forcefully representing the importance of equity in expectations. Agreements on Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) struck by Prime Minister Modi and then US president Barrack Obama were critical to India and many developing countries agreeing to the

Paris Agreement.

Since then, India has been one of the few countries on track to meet its NDCs.

As of this printing, India has not filed its revised NDCs and has been vocal in its resistance to set a mid-century net zero commitment which it argues is counter to the CBDR. In essence India is demanding equitable decarbonisation and development.

India argues that the countries demanding a net zero commitment have not made adequate progress either against their own goals or commitments to promises to fund mitigation and adaptation projects.

Despite this, India has indicated an openness to negotiations and indicated it intends to support enhanced cooperation on a number of initiatives including technology transfer and carbon-credit markets. It is also a significant supporter of Loss and Damages financing. India continues its green transition efforts.

Silver Linings: Business and Finance

This COP is expected to see unprecedented levels of business and private financial commitments. If mechanisms are established to add accountability to these pledges, it can help exceed targets, fund the transition and impress upon government the importance of stepping up.

COP26 will likely not meet the ambitions or expectations that have been established by its agenda. Revised NDCs will likely not meet the preferred pathway to keep temperatures below 1.5 degrees increase. It will likely be called a failure. But another COP will happen in a year and governments cannot solve these problems on their own.

-

China, the US and India are the three largest polluters in the world

The Crown Jewel of COP 26: Renewed NDCs

Without significant ambition in the renewed contributions from the US, China and India, it may be mathematically impossible to meet the 1.5 degree Celsius goal set out in the Paris Agreement.

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep the average global temperature change to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and ideally limited to 1.5°C. Given the vast difficulties in getting 180+ countries to agree, it was structured so that each country establish NDCs to establish a pathway to meeting the requirements of the agreement.

To enable countries to make palatable near-term commitments, the agreement mandates signatories to update (to be read as increase) Nationally Determined Contributions every five years. The benefits of this approach are that it provides the flexibility to address new or changing realities and also builds in accountability to (and pressure from) the global community to meet environmental objectives.

A May 2021 report from the World Meteorological Organisations (WMO) noted that certain regions have already hit an average 1.5 degree temperature increase and there is a 40 per cent chance the average global temperatures will reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels in at least one in the next five years.

Many countries are already behind on meeting NDCs and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has warned that even if existing climate pledges are met, emissions will be 27 per cent and 38 per cent higher than is needed to limit warming to 2C and 1.5C, respectively. This puts the planet on track for 2.7 degree warming, a result experts describe as catastrophic.

As of 25 October 2021, United Nations Climate Change released a Synthesis Report to assess the progress and prospects of climate commitments. Including the 116 new or updated NDCs communicated by 143 Parties received by 12 October 2021.

Total GHG emissions for the 116 NDCs that have been updated are estimated to be 9 per cent below 2010 levels by 2030 and as much as 83-88 per cent lower in 2050 versus 2019. Conversely, when the NDCs of all 192 signatories are evaluated as a whole, 2030 emissions are projected to be 16 per cent above 2010 levels. These projections assume all parties meet their NDCs, an accomplishment few countries can currently claim.

China, the US and India are the three largest polluters (unless Europe is evaluated as a block versus individual countries). The updated commitments from China and the US fall woefully short of what the global community expected. As of this writing, India has not submitted its revised NDCs and continues to negotiate expected tradeoffs.

-

Who will Pay the Piper?

Climate Finance and economics, taken together, has singularly been the greatest obstacle to achieve Climate Agreements or action.

The premise that developed countries caused the damage and reaped the economic benefit at the expense of poor countries is overwhelmingly and widely accepted but still the source of many hard questions.

What is the price of past pollution? Where does financial responsibility begin and when does it end?

Now that we know better, what is reasonable pollution by developing countries?

Why should poor and developing countries continue to subsidise the environmental and economic consumption of developed economies?

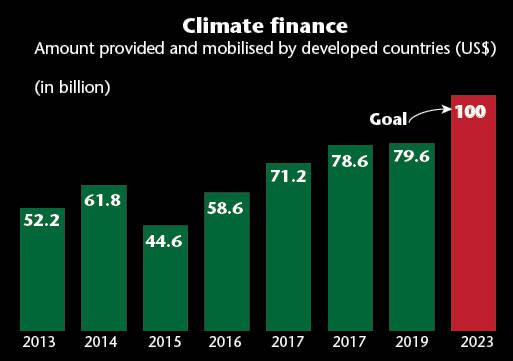

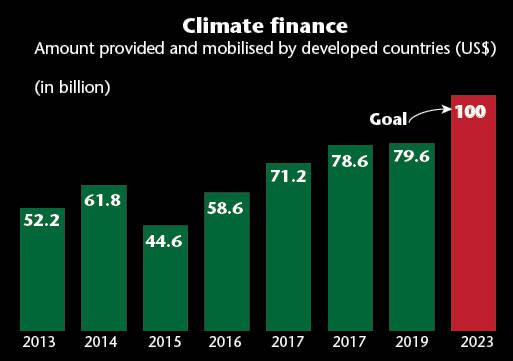

Disparate answers have sunk many climate negotiations through the years. In 2009, developed countries pledged to provide poor and developing countries $100 billion annually to fund mitigation and adaptation efforts. Failure to ratify the fund was one of the most contentious issues of the Paris Agreement, which was ultimately reached with OECD countries committing to meet the commitment by the last day of 2020.

Raising the fund was a cornerstone of the UK agenda when it assumed the COP presidency in 2019. Despite the US doubling its commitment twice this year and other countries also increasing commitments, it is now estimated that the $100 billion goal will only be reached in 2022 or 2023.

Developing countries, including China and India, have explicitly condemned the OECD countries for this failure, noting a history of broken promises and inequitable demands for decarbonisation and timelines for net-zero commitments. It is notable that India has still not released its revised NDCs but has publicly avoided net-zero commitments, while China has released revised NDCs that peg its net-zero ambitions at 2060, instead of 2050.

Negotiators for developing countries have further detailed demand for over $750 billion in annual funding. Always a contentious issue, the gap in funding is expected to be a particularly acute topic this year, in light of the global pandemic magnifying skewed economic recovery and access to vaccinations.

Private finance is expected to be a significant source of funding for developing countries. Despite significant pledges by global asset managers, private funding accounts for less than 20 billion of the 80 billion so far committed for 2021.

Debate on the fund is not limited to its amount. The fund was originally envisioned to be split 50-50 with funding for both mitigation and adaptation; however, the majority of money deployed funds mitigation efforts and recipients complain that there is not enough funding available for adaptation initiatives.

Exclusive of the 100 billion annual fund, poor and vulnerable countries – those most likely to experience the side-effects of climate change and with the least ability to pay for recovery – are also advocating for Loss and Damage Financing.

Loss and Damaging Financing is meant to be direct compensation to poor and vulnerable countries to pay for recovery from and adaptation to both extreme climate events (fires, floods, droughts, etc) and slow onset disasters like rising sea levels. Given the billions of dollars of damage already documented annually, developed countries are strongly opposed to this unlimited financing responsibility.

-

The Methane reduction initiative aims to cut methane emissions by 30 per cent

Setting the Rules of the Game

Rules – the terms, timeframes, regulations and requirements – must be agreed by all parties for a deal like the Paris Agreement to achieve its objectives. In Paris, negotiators agreed to establish the rules and mechanisms to make the agreement enforceable but were not able to finalise all of the terms.

In each of the following COPs, negotiators worked at finalising the ‘Paris Rulebook’. Each year, progress was made and COP25 was expected to be the year it was finalised; however, each year to date it has not been fully agreed.

The rulebook is intended to establish common methodology to measure and report greenhouse gas emissions and progress towards meeting NDCs in a transparent, verifiable, and comparable way. Article 6 outlines that the rules are also expected to govern areas that cover international cooperation such as trade, carbon markets and development aid. Article 6 and reporting formats are the key remaining area of contention.

The hotly contested debate is focused on how to count and attribute emissions and credits in the case of cross border trade, aid, investment and carbon markets. Each of these points and related calculations require agreed reporting and verification rules to ensure environmental integrity and prevent double counting of emissions reductions.

Specifically, certain high emitting countries want to receive credits for investing in carbon reducing initiatives in poor or developing countries, while developing countries require credits and offsets to balance growth. Similarly, low-income, export-dependent countries wish to attribute emissions for exported goods to be attributed to the destination country.

Guidelines and market mechanisms for a global carbon market, similarly, must align with many competing regulatory regimes. Many poor and developing countries, often producers of credits, advocate for certification systems with more affordable, transparent and less cumbersome requirements, noting that the high cost and technicality can prevent project participation or the accrual of economic benefit.

Reporting formats and equations are another area of dispute. Poor and Developing countries see some of the formats and verification mechanisms as unnecessarily technical or expensive to comply with.

Calculations for the Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (CO2E) of several Green House Gases are contested by parties with particularly high emissions. The debate on methane is expected to be heated this year as the discussion on methane potency – it has 80x more warming power than CO2 over the first 20 years – clashes with the economic recovery of developing countries, including those with large meat and animal industries.

The Methane reduction initiative aims to cut methane emissions by 30 per cent, while a group of meat producing economies, now struggling with post pandemic economic recovery, already spiked methane accounting rules in 2019.