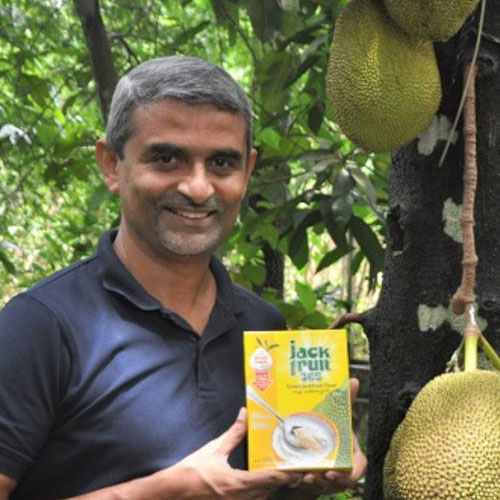

Eight years ago, James Joseph was a man with an ambition in Microsoft – a company in which he had spent a large part of his 25-year career as a tech veteran. Flying around the world to meet customers and partners, he made it a point to network whenever possible. He had created his own work-from-home model, long before it became a concept thanks to the coronavirus pandemic: he operated from his native village near Kochi in Kerala but travelled a large part of the month. Joseph had helped launch a number of products within the software giant, and was sure he would be made the company’s CEO for incubators. “Managing new products is like a start-up,” he explains. “I lost out at the last minute – I was told I had no start-up experience!” He was ‘totally fed up’ and took a year off to write a book. Sitting at his window working, he saw the jackfruit trees in his yard every time he lifted his head from his laptop. By the time he finished his God’s own office, a take-off from the fact that Kerala is known as ‘God’s own country’, Joseph was bursting with a new idea on using the fruit of the tree. Priest’s message A ‘meeting with his father-in-law’s parish priest sealed it: he had been taking raw jackfruit for five years and it had helped bring down his sugar. He approached spices major Eastern to take it on and make the product, but they advised him to go ahead himself, with their full support. “That fell on me like a ton of bricks!” he says. “But I had no choice.” So he did: and jackfruit365, a green jackfruit flour priced at Rs400 per kg in the retail market, with a shelf life of a year, came into existence, as a diet supplement for diabetics. The product has gone through a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with the results published in the American Diabetes Association (ADA) journal Diabetes. The study showed a significant decrease in the fasting and post-prandial glucose levels as well as HbA1c (glycosylated haemoglobin) count within three months among participants taking 30 gm of jackfruit365 every day, as a replacement for an equal volume of rice or atta.

-

Traditionally, as much as 80 per cent of the fruit grown in Kerala – worth over Rs2,000 crore – ended up as waste every year, because of its size, which made it difficult to package and transport: Courtesy: Pixabay