-

Guha: the SC has done little to stop the degradation

Edicts and FDI cap

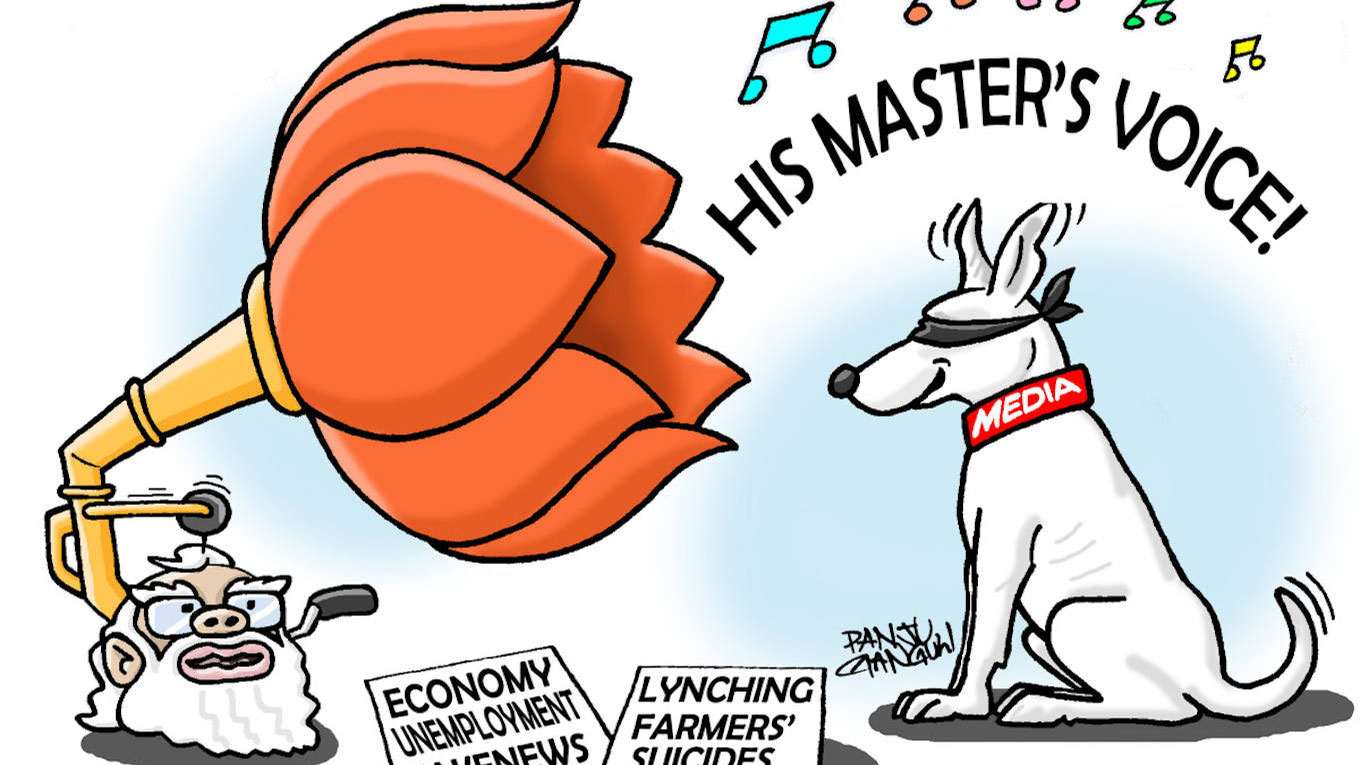

What has made the picture murkier are the overt attempts to control the narrative in the media. Ever since Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumed office, the Right to Information Act, an important tool for journalists as well as alert citizens, was rendered toothless. The Central Information Commission, meant to channel request to the government for information, either remained understaffed or was discouraged from fully discharging its duties.

An alert and proactive judiciary could have been a valuable ally of a Fourth Estate under pressure. Indeed, at a time when faith in democratic institutions is far from buoyant, the judiciary should have been a beacon of hope. But that was not to be. Sometimes, there comes a judgment, which, at first glance, appears promising but somehow seems to wilt under more direct scrutiny, owing to the court’s lack of response to significant prayers in the petition.

Last year, when historian Ramachandra Guha wrote an evocative open letter to the judges of Supreme Court on the growing lack of faith among many Indians in the functioning of the top court, he was reflecting the views of many in the media as well. “While the SC cannot be blamed in any way for why and how this degradation of Indian democracy originated, it has, in recent years, done little to stop or stem it,” Guha wrote.

In December 2019, as protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act passed by Parliament erupted in cities across the country, the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting issued an advisory to private television stations not to broadcast images of protests. In a veiled warning, the advisory said that the Prime Minister wants broadcasters to ‘abstain’ from showing content that’s ‘against the maintenance of law and order or which promotes anti-national attitudes’. That was perhaps the signal for the Delhi police to detain several journalists, who were covering an anti-CAA march to Rajghat. A month earlier, media covering the peaceful protests by Jamia Milia Islamia students also had been manhandled by Delhi Police.

The line of investment and capital flowing into the Indian media’s coffers was further choked off when the government further reinforced the 26 per cent limit on foreign direct investment in the digital media sector, first announced in September 2019. Before that, the FDI caps had existed only for the print media (at 26 per cent) and news broadcast television companies (49 per cent). The government justified its action by saying that it was guided by the need for a level playing field for FDI in all forms of mass media.

The first collateral victim of this decision was Huffpost India. Founded as Huffington Post in 2005, the website gained readership in the dying years of the George W. Bush administration in the US. It arrived in India — its 13th global edition — in late 2014, in partnership with The Times of India group. The partnership collapsed in 2017, but HuffPost India was relaunched soon after. Later, Verizon Media, which owns Huffpost, closed down the India edition. The move coincided with HuffPost’s acquisition by BuzzFeed. Its shutdown was a strategic decision taken by BuzzFeed, which felt that regulatory environment in India, along with Brazil, did not encourage foreign ownership of news websites.

-

Sugathan: indirect control is a matter of concern

These government moves coincided with the New Media Policy (NMP) issued by the Jammu & Kashmir government, an adjunct of the Union home ministry now, in the summer of 2020. The NMP is full of implicit threats like, “Any individual or group indulging in fake news, unethical or anti-national activities or plagiarism shall be de-empanelled (shorn of official recognition and access) besides being proceeded against under the law.”

Then came the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021, which will govern social media firms like Facebook, Twitter, Google and so on, messaging apps like WhatsApp OTT platforms, such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney Hotstar, and the digital news media. The rules related to social media will be administered by the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology, while those for OTTs and digital media will be administered by the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting.

The rules set up a classification of ‘publishers of news and current affairs content’ (‘digital news portals’), as part of ‘digital media’, and sought to regulate these news portals under Part III of the Rules (‘Impugned Part’), by imposing government oversight and a ‘Code of Ethics’.

The FDI cap and the new rules have alarmed digital news organisations. DIGIPUB News India Foundation, a consortium of such organisations, says: “The government's policy interventions and prescriptions could seriously limit that potential (of the digital news industry) rather than provide a growth conducive to environment in Indian companies and the Indian digital sector. Besides, they put Indian companies at a serious disadvantage to foreign news brands, and disincentivise entrepreneurs from incorporating companies in India that could be a part of the India growth story". DIGIPUB’s founder members include Alt News, Article 14, Newslaundry, Scroll, The News Minute, The Quint and The Wire.

Many digital platforms have now challenged the new IT rules in court. The Delhi High Court has issued notice to the Union government on a petition filed by the Foundation for Independent Journalism (associated with The Wire) on the new rules which, it said, seek to dictate content to digital news media platforms, go beyond the scope of what is permissible under the IT Act and need to be struck down.

Prasanth Sugathan, legal director, SFLC.in, a digital rights organisation, says that when digital news portals get controlled in indirect ways like regulating their access to investment and capital, it is a matter of concern. The I&B Ministry has also asked digital news media players that have an equity structure with more than 26 per cent foreign investments to reduce this to the prescribed norms by 15 October 2021 with the Ministry’s approval.

OTT takes a hit

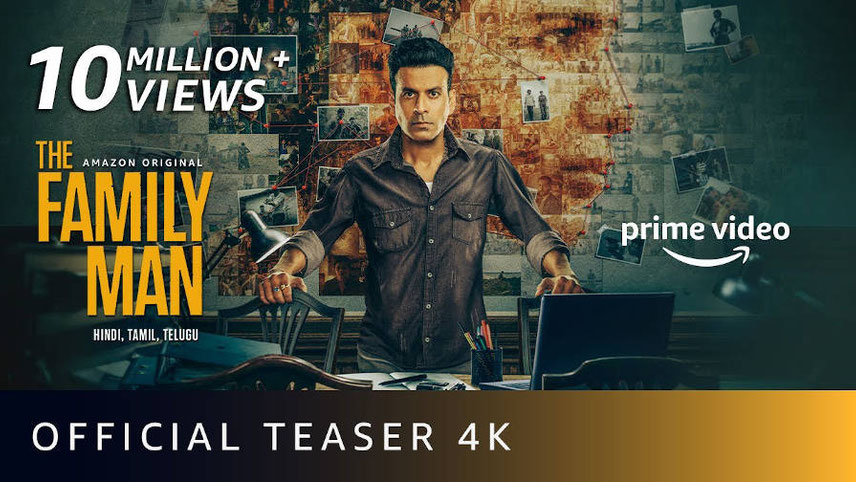

The impact of the new rules is also being felt in streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, with the latter cancelling two upcoming shows, spy thriller The Family Man and crime series Paatal Lok. The OTT platforms were earlier outside the purview of the government’s control and had gained a whole legion of new subscribers, as lockdown rules shuttered the cinema halls, depriving people of this form of mass entertainment. Amazon, for now, has also stalled a show by film-maker Vishal Bhardwaj based on the Kandahar hijack, while the release of Disney+Hotstar’s Kamathipura, based on the red-light district in Mumbai for International Women’s Day, was postponed indefinitely.

-

The new rules hit the OTT platforms hard; shows like The Family Man has been cancelled

Streaming platforms generally work with the principle that, while it is ideal to err on the side of caution, in a free society, all kinds of content should be allowed as long as it comes with safeguards like age classification. However, since topics such as sex and nudity have now been restricted to older audiences as part of specific age classifications, OTT platforms will need to develop a strong system of age verification. Also, parental locks, if desired, will have to be imposed on every single episode of a particular series, making for a cumbersome process.

Choking off start-ups

International news aggregation platforms are today multi-billion dollar assets and the move to restrict FDI for news aggregators can come in the way of similar Indian start-ups coming up in the space, due to restrictions on capital sourcing. The digital media space has been attracting substantial foreign investments in the last few years and has been creating significant employment opportunities in India. It is somewhat ironic that the government should target the New Age digital media, gaming, VFX and OTTs segments are also attracting a lot of young minds and talent.

More could follow if the government goes ahead with its plans. In November 2019, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting released a draft Registration of Press and Periodicals Bill 2019 (RPP: 2019) for stakeholder consultation. The bill seeks to replace the Press and Registration of Books Act, 1867 (RPP: 1867), which the British government enacted to curb the role of the press as the institutional opposition to its rule after the Revolt of 1857. The RPP 2019 underlines the requirement of registration for every periodical (a broader category than just newspapers, including magazines and journals), as well as the power to revoke registrations. It smacks of the colonial model of ‘proprietor control’ – the use of licensing and registration requirements to enable the exertion of pressure on the proprietors of a newspaper.

It goes on to disqualify any person convicted of an offence “for having done anything against the security of the State” or convicted under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, from ‘bringing out a publication’. While conviction under the UAPA might be a justifiably narrow disqualification, phrases such as ‘security of the State’ are vague and have historically been prone to capture by ruling dispensations to meet their ends of political self-preservation. Further, recent instances of the use of the UAPA to clamp down on journalists and civil society activists makes this disqualification all the more troubling (see Box: The UAPA sword). Interestingly, the Bill also has a provision which declares that rules for the registration of “news on digital media” may be prescribed.

-

Pahwa: internet shutdown is also censorship

Plain paranoia?

It is somewhat inexplicable that a government which came to power with such a resounding majority in 2019 should so soon become paranoid about criticism and mount pressure on news outlets, which do not see eye to eye with its policies. Countries such as China and Iran have long kept tight control over online media, but human rights and internet activists say that India figures prominently in the list of democratic governments that are now using internet cutoffs to stifle free speech under the guise of fighting terrorism (as in Kashmir).

India recorded the world’s highest number of Internet shutdowns in 2020, the longest shutdown being in Jammu & Kashmir. The Internet is the backbone of modern civilisation and drives innovation in everything from education to healthcare, from social media to entertainment and from mission-critical applications to opening newer horizons of knowledge. The UN has even declared it to be a human right. The Modi government has rightly earmarked Internet access to all Indians as one of its top priorities, through projects such as Digital India.

However, its approach with respect to Internet shutdowns has surely not been democratic and transparent. “Internet shutdowns are a disproportionate act of censorship of freedom of expression. Besides, the cost of Internet shutdown is real,” says Nikhil Pahwa, digital rights activist and founder of news portal Medianama.

Whither democracy

Prime Minister Modi’s advice to media owners, proffered a day before his dramatic announcement of the national lockdown to counter the pandemic that they should run ‘positive stories’ at this time of the pandemic was a curtain-raiser to the shape of things to come. The government did not take too kindly to the media as it went about highlighting the migrant crisis – vividly through photographs, and poignantly through the heart-breaking stories of thousands of men, women and children setting out to walk hundreds of kilometres to their distant homes, because there was no source of sustenance in the cities where they had slaved for years.

The discriminatory targeting of Muslims during the Tablighi Jamaat incident in Delhi; the ill-planned Covid-19 lockdown; the disturbing endorsement of an unscientific Covid-19 ‘cure’ by the health minister; Modi’s initial claim that there had been no Chinese intrusions along the Line of Actual Control; and the lingering Kashmir crisis, were among the other episodes that the media zeroed in on to show up the government in a poor light.

Peeved by the reporting on the lockdown, the government asked the Supreme Court to impose a nationwide censorship on the publication of information that the government deemed ‘false or inaccurate’. The Supreme Court, of course, denied that request, but it did direct the media to refer to the ‘official version’ of events when covering the pandemic — an ambiguous edict which has mercifully not been enforced.

In countries like the US, the UK, Japan and Europe, the news coverage of the pandemic was framed around scientific research, frontline healthcare workers and the domestic and global outbreaks. But, soon, the media’s focus, in all four countries, shift to domestic and international economic consequences and financial fallout — a topic that has largely remained a focus in most of the countries they analysed. In India, the pandemic brought out the fault-lines in our society, economy and polity which the media could not ignore.

-

Gupta: government takeover of journalism

Stung to the quick, the government set up a Group of Ministers which, as disclosures now reveal, met six times over June-July 2020 to discuss the need to ‘neutralise’ independent media, of pulling in ‘right-wing parties of other countries’ into propaganda efforts, of the need to ‘track’ those who ask questions and of ways to rope in “productive and supportive journalists". Since then, the authorities, mostly in states ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party, unleashed a calibrated strategy of targeting organisations, activists and journalists who have been asking uncomfortable questions by filing police cases against them.

The misuse of Epidemic Diseases Act (EDA), drafted by the colonial state in 1897 “to take special measures and prescribe regulations” for “the better prevention of the dangerous epidemic diseases” became commonplace. Indeed, a toxic mix of the Disaster Management Act, 2005, Section 144 of the CrPC and the Epidemics Act came in handy to criminalise media criticism and dissent. The Mumbai Police invoked the EDA to arrest a journalist, alleging that his social media posts led to unrest among migrant workers in suburban Bandra.

The Gujarat government combined the sedition law with the Disaster Management Act to charge a journalist for reporting that the Chief Minister Vijay Rupani may be removed by the BJP’s Central leadership for his handling of the pandemic. The Gujarat high court quashed the case after the journalist issued an ‘unconditional apology’ in November. At least four FIRs were filed against journalists in Himachal Pradesh for highlighting the condition of stranded labourers in the pandemic. The FIRs alleged that these reports are ‘fake’ and ‘sensational’ news.

The coverage of the farmers’ agitation also became a lightning rod for the government. A large section of the media, particularly visual media, buckled under the warnings and advisories being issued by the government. In the race for TRPs, several media outlets sought to find a way out by resorting to mindless jingoism.

India is justly proud of its position as the world’s largest democracy; it is often said that the democratic world in fact is rooting for India’s success. However, India has no reason to be proud of the fact that it has become a hotbed for the spread of Covid-19, with an estimated 90,000 daily infections daily at one stage, second only to the US. If the press had legitimate questions on the handling of the pandemic, the government should have answered them, finding a way to combat the virus while preserving the democratic values that define the nation.

Joel Simon, executive director, The Committee to Protect Journalists, an independent, non-profit organisation based in New York that promotes press freedom worldwide, points out that India has long been a leader and an example in the democratic world, but the Indian government’s handling of the media coverage of the pandemic has weakened its position. “At the heart of any democracy is an informed citizenry that is empowered to make decisions and hold its government accountable. That is why there is nothing more essential to a democracy than a free press. It is not merely the means through which citizens gather information. It is the vehicle through which ideas are debated, policies are formulated, and conflicts are resolved. Yet, India’s press freedom record has seen a decline in recent years.”

-

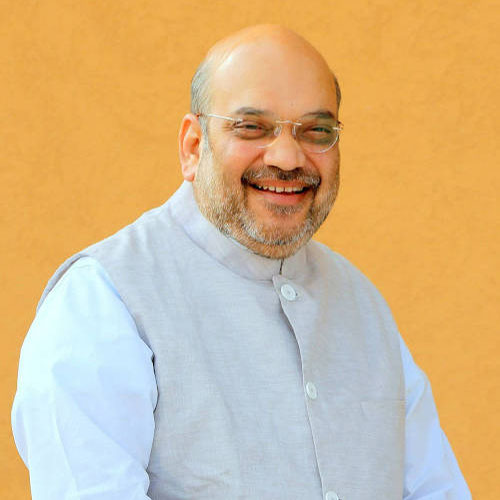

Shah: applauding media’s role during Covid-19

New rules raise hackles

Perhaps, no other rules attracted the kind of criticism than The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021. Critics say that the regulations imposed in February allow for greater government control over online content, threaten to weaken encryption, and would seriously undermine rights to privacy and freedom of expression online.

The government can order digital news media to remove any content under Section 69A of the IT Act which “threatens the unity, integrity, defence, security or Sovereignty of India, friendly relations with foreign States, or public order, or causes incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence or prevents investigation of any offence or is insulting any foreign states.”

The new rules have raised the hackles of several organisations like Human Rights Watch, Internet Freedom Foundation and the Committee to Protect Journalists. Human Rights Watch has pointed out that the new rules put the onus on all platforms to disclose to the government the original source of any information — e.g. the original source of a WhatsApp message.

If this happens, then messaging cannot be end-to-end encrypted. Internet Freedom Foundation has noted that these new rules are not based on any parliamentary approval and have been ‘arbitrarily made’ using Section 79 of the IT Act. The government has sought to arm itself such powers when current laws — from defamation to contempt of court — already exist.

The new IT rules envision a three-tier regulatory system with government officials calling the shots at the top. In the first tier, platforms must appoint an internal compliance officer who decides whether a complaint against content published by the platform is to be upheld, in which case the platform may be asked to withdraw the story or publish an apology or correction.

The second tier consists of associations set up by the platform to form an oversight body. The complainant may approach such a body should they be dissatisfied with the way their complaint was handled at the first level. The final tier is meant to be an inter-ministerial committee consisting of secretaries in the Central government, which can take down content that somebody is complaining about or shut down a website altogether for some time.

Some industry leaders have slammed the rules. Shekhar Gupta, Editor-in-Chief, The Print, a digital media platform, writes, “This is a government takeover of journalism and free speech in India.” Gupta argued that the press already self-regulates based on ‘mature understanding’; media is already bound by the Press Council of India’s code of ethics, while cable TV and other networks follow a programming code. “So, these are strong, arbitrary powers,” observed Gupta. The government presence could have a chilling effect on free speech and conversation.

However, one rule that has been generally welcomed is the need to register with the government because, as Gupta points out, “anybody can set up a website nowadays and claim to be a news media organisation”.

Government’s defence

Engaging with the Digital News Publishers Association, which includes media organisations such as India Today, The Indian Express, Hindustan Times and The Times of India, to discuss the newly notified rules for digital media, I&B minister Prakash Javadekar noted that print media and TV channels have digital versions whose content is almost the same as that on the traditional platforms. However, there are contents, which appear exclusively on the digital platform. Also, there are several entities that are only on the digital platform. Accordingly, the rules seek to cover the news on Digital Media so as to bring them at par with the traditional media.

-

Prasad: there are concerns

According to a press release put out by the ministry, the participants welcomed the new rules, but added that TV and news print media have been following the norms of the Cable Television Network Act and the Press Council Act respectively for a long time. Further, for publishing the digital versions the publishers follow the existing norms of the traditional platforms. The publishers said they feel they should be treated differently than those news publishers who are only on a digital platform.

So, on the face of it, there appears to be a divide (or the government is trying to give the impression of one) between the plain vanilla digital media and bigger media organisations which have a digital presence.

Defending the new rules, Ravi Shankar Prasad, minister for Law & Justice, IT & Electronics, says ordinary people are empowered by the social media. However, there are concerns about the misuse of social media as well. “Today, some people who file cases want a particular judgment to come on those cases. If the judgment is not in accordance with a social media campaign, the judges are trolled.” He goes on to ask, “Is it not a fact that our PM Narendra Modi is the biggest victim of falsehood campaign for more than 20 years, based upon utter lies?”

Amid the hullaballoo last year over the government’s covert and overt attempts to gag the media, Union Home Minister Amit Shah, in a tweet on National Press Day (16 November), said, “Modi government is committed towards the freedom of press and strongly opposes those who throttle it. I applaud media’s remarkable role during Covid-19”. That was in line with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s statement made a few months earlier: “Our newspapers and magazines should have a global reputation.” And he lauded the Indian media for its coverage for Covid-19 and government-led rural empowerment schemes, such as ‘Swachh Bharat’, ‘Ujjwala’ and now ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’. To be fair to Modi, he also acknowledged the importance of media critiquing government actions and helping them improve.

But, as critics asked, has the government done anything – or even adopted a hands-off approach – that serves to sustain a free and vibrant media?

Media’s golden years

Many juxtapose the restrictions being put on the media now with the unfettered run it had in the 1900s and early 2000s. The media had then grown into an economic giant, with a business turnover which exceeded 1 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and matched the economic size of many individual industries. In fact, it was considered the world’s most dynamic media industry and one of the fastest growing anywhere. The media’s worth was equivalent to half the value of India’s famously successful computer software exports.

The media business clocked double-digit growth annually, which clearly outpaced India’s GDP growth rate, which itself rose from about 5 per cent to almost 9 per cent a year. Amazingly, India’s print media bucked a worldwide trend. In 2010, it grew by an estimated 26 per cent. This was a different scenario from the state of the media in much of the world. In most developed countries, the media had reached saturation point. The western print media was especially badly off, with falling revenues; it shrank as major newspapers lost money and circulation and cut staff and coverage.

-

In India, investigative journalism took the shape of sting operations, which exposed cricket match-fixing scandals and wheeling and dealing in defence matters. The 2G spectrum and coal mines allocation scandals were also exposed by the media. It goes to the credit of former Prime Ministers Atal Bihari In India, investigative journalism took the shape of sting operations, which exposed cricket match-fixing scandals and wheeling and dealing in defence matters. The 2G spectrum and coal mines allocation scandals were also exposed by the media. It goes to the credit of former Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpyee and Manmohan Singh that, despite the political discomfort they suffered during their tenures due to journalistic investigations, press freedom did not become a casualty.

The media’s subjugation during the Emergency was a dark chapter that has been well-documented, as has been the efforts of the Rajiv Gandhi regime through the ill-advised Defamation Bill. Some states, notably the Congress-ruled Bihar under Jagannath Mishra, also earned infamy for bringing black laws to throttle the press.

Indeed, the casting of the media as a social evil and the state’s role in tightening the reins on the fourth estate is not a new thing. The Modi regime in particular has seen a severe curbing of the freedom of expression and freedom of press through several means, including fostering the practice of self-censorship among media organisations and individual journalists. Figuratively, journalists these days need to look over their shoulder before speaking their mind.

Circumspection also has become the standard operating procedure. With all this happening, there is a fear of yesterday’s watchdogs becoming today’s lapdogs.

Meanwhile, Modi’s promise made in the run-up to the 2014 election of building a ‘digital India’, where ‘access to information knows no barriers’ has fallen apart. India’s digital realm is now one of the most heavily regulated of any major democracy.

-

Morrison: making big tech cough up

Dragging its feet

At a time when progressive governments in Canada, Singapore and European Union are thinking of following the footsteps of Australia in enacting a law with respect to making Google and Facebook pay local news publishers for using their news content, which is proprietary material, the government in India has chosen to skirt the issue. The issue was recently flagged in Parliament by Sushil Kumar Modi, a senior BJP MP in the Rajya Sabha.

He demanded that Google and Facebook must pay their fair share of earnings they make from news content to Indian publishers. Modi, a former deputy chief minister of Bihar, urged the government to consider mandating ‘tech giants’ such as Google, Facebook and YouTube (owned by Google) to their revenue with traditional media outlets, accusing them of being the cause of severe financial distress in the media industry.

The same day Sushil Modi intervened in the Rajya Sabha, four other BJP MPs had asked the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology (MEITY) in the Lok Sabha on whether the Indian government had taken note of this subject, and what it was doing about it. In his written reply, junior MEITY minister Sanjay Dhotre avoided a clear-cut response. Minister of Information & Broadcasting Prakash Javadekar had earlier informed the Lok Sabha that, 'there is no proposal for enactment of a law by the Government in this regard.'

The Australian legislation – called News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code Bill 2020, which was passed on 25 February by the Australian Parliament – mandates a bargaining code that aims to force Google and Facebook to compensate local news companies for using their news content. Closely watched by the world over, the legislation sets a precedent in regulating social media across geographies. Indeed, most democratic governments are not averse to helping cash-strapped media companies, hit badly by the Covid-19 pandemic. Getting Facebook and Google to pay for a share of the cost of news gathering is one way of shoring up the companies’ revenues. But that’s hardly the Modi government’s concern now.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has said that he’s discussed the new law with the leaders of India, Canada, France and the UK. Yet, the first authoritative comment from the Indian government on the growing demand for making Big Tech cough up to news content publishers has been wishy-washy. The Indian newspaper industry has been arguing that producing credible news takes money as journalists have to be hired and news gathering infrastructures created. Indian Newspaper Society (INS), the apex body of the print media industry, has asked Google India to compensate Indian newspapers for using their content ‘reasonably’.

"News is not a commodity, and it costs money,” asserts Jayant Mathew, chairman, INS Digital Committee. “Without news, Google can't function as it will just be a B2B listing site. We wrote to Google seeking payment for our content and are awaiting their response. Depending upon the answer, we will approach the Competition Commission and government for framing similar legislation. "

-

In India, Google and Facebook are raking in more advertising money than The Times of India or Hindustan Times or any other large Indian newspaper. In fact, almost 90 per cent of Google’s revenue is derived from advertising. According to regulatory filings, Google's India revenues rose to about 35 per cent to touch Rs5,593.8 crore in 2019-20 over the previous fiscal year, primarily driven by advertisements. This is outside of the revenues garnered by Google AdWords, the company's biggest cash cow, which is registered under the Google Asia Pacific division.

The newspaper industry is buzzing with speculation about why the government is avoiding a decision on the issue, allowing BJP MPs to flag the issue in Parliament but not committing itself either way. Javadekar merely says that “India is closely following the developments with respect to making social media platforms paying for news content.”

Observers see a reason in the government’s delay in formulating a response. Possibly, the government may use it as leverage in its future dealings with the domestic media. Besides, the Modi government has viewed the Silicon Valley companies and their platforms as tools in its quest to create Digital India.

Also, there is a limit to how far the government can go in forcing Big Tech companies to cough up more cash. As it is, Big Tech companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter are expected to pay significantly more tax in India as a result of the government’s new social media rules. Complying with the new media guidelines would mean hiring Indian residents to head compliance as well as nodal and grievance offices. This would mean setting up permanent establishments here which the Income Tax establishment may treat as ‘liaison offices’.

-

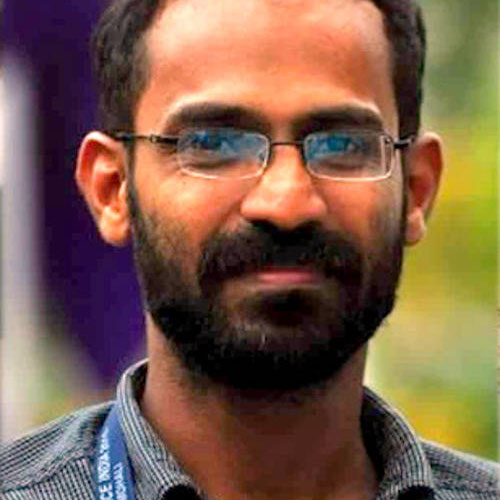

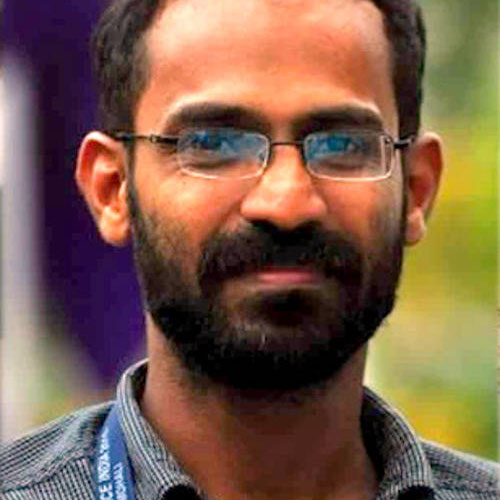

Kappan: victim of a draconian law

The UAPA sword

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), a draconian anti-terrorism law under which a person can be designated a terrorist and jailed for up to seven years, has been used indiscriminately by state police organisations to haul up nosy journalists. Nothing signifies the misuse of UAPA than the FIR filed on 20 April last year by the J&K Police against Kashmiri photojournalist Masrat Zahra.

The police, however, refused to call her a journalist, identifying her in its press release as a ‘Facebook user’. Citing the posts it claimed were violative of the UAPA’s provisions, the police posted a screen grab of a photograph by Zahra, which she had uploaded on her Instagram account in September 2018. The photo in question is of Shia protestors holding aloft a poster of Burhan Wani, the Hizbul Mujahideen commander killed in an encounter a few years ago. The poster is labeled (in Urdu) ‘Shaheed Burhan Wani’ and Zahrah’s description of the photo on Instagram duly reflects that.

Why it took the police more than 16 months to decide the posted image merited penal action is a mystery, considering the photograph in question happens to be the property of Getty Images and is still accessible on its website. The problem is that the act’s provisions allow for such a wide range of interpretations that they leave journalists, particularly in Kashmir, vulnerable to its charges. For example, it describes ‘unlawful activity’ as action – the spoken and written word included – that ‘provokes disaffection against the country’ or supports claims of India’s territorial dismemberment or questions its sovereignty.

And Section 39, which covers the ‘offence relating to support given to a terrorist organisation’ says that a person who ‘invites support’ for the terrorist organisation would be guilty of this offence. What inviting support means is not defined but it says this need not involve providing money, which is covered by a different section.

It is not hard to see how normal journalistic writing that either reports facts inconvenient to the government or analyses the Kashmir problem from the perspective of the need for apolitical resolution could easily fall foul of these sweeping sections. In most cases, the police do not adhere to Supreme Court guidelines on the journalist’s arrest among other directions. According to the SC guidelines, “time, place of arrest and venue of custody of an arrestee must be notified by the police where the next friend or relative of the arrestee lives outside the district or town through the legal aid organisation in the district and the police station of the area concerned telegraphically within a period of 8 to 12 hours after the arrest."

The problem is not limited to Kashmir alone. From UP to Manipur, journalists have been arrested under UAPA. Last year, in October, the UP Police arrested journalist Siddique Kappan, who worked as a Delhi correspondent for Kerala based website Azhimukham. He was on his way to Hathras to report the situation after the alleged gang rape and death of the 19-year old Dalit woman. The FIR accuses him and three others he was travelling with of hatching conspiracy to ‘incite riots and to disrupt peace in the area’, among other charges.

The four were slapped with various charges under sections 124A (sedition), 153A (for promoting enmity between groups) and 295A (outraging religious feelings) of the IPC, sections 14 and 17 of UAPA, sections 65, 72, and 76 of the IT Act. The UP police claimed that Kappan and his fellow passengers were from the Popular Front of India (PFI) -- a Kerala-based hardline Muslim organisation that authorities often accuse of having links with extremist groups and the state government wants it outlawed.

The Kerala Union of Working Journalists' Delhi Unit filed a filed a habeas corpus petition at the Supreme Court. Lawyer Wills Mathews, who is representing Kappan, says he was allowed to meet him only after 47 days. In February, the Supreme Court granted Kappan a five-day interim bail to visit his 90-year-old mother, who was bedridden and ailing in Kerala.