-

Singh: accused of favouring Meiteis

In Manipur, however, the Meitei demand for ST status found more resonance, as it is the dominant community in the state. The CM is a Meitei as are senior ministers and bureaucrats. The Meiteis’ aspirations are not dissimilar to politically dominant castes in other states seeking a larger share of the reservation pie in government jobs and education.

Of late, many powerful landholding castes like Patels in Gujarat, Jats in Haryana, Gujars in Rajasthan, Marathas in Maharashtra and Kapus in Andhra Pradesh have demanded reservation. Down in West Bengal recently, Kurmis blocked railway lines to add muscle to their petition for ST status. The Manipur violence is only the latest reminder of growing pressure on land and shrinking economic opportunities. Indeed, this twin economic challenge now spans most states.

Growth irony

The phenomenon underscores the irony of India’s growth. At 1.42 billion, India has just overtaken China as the world’s most populous nation. Booming populations bring opportunities for economic growth, if certain factors are capitalised on in a time-bound fashion. According to the latest UN Population Fund report, 25 per cent of our population is in the age group of 0-14 years, 18 per cent in the 10-19 age group and 26 per cent, in the age bracket of 10-24 years.

The success of the East Asian Tigers is a good example of how demographic bonus can be used to reap benefits. Our next-door neighbour China is the best example of how a young population was provided employment skills and the skilled labour force played a major role in achieving fast economic growth.

However, in India, while our skilling programmes for youth and labour are yet to take off, the growing population is only adding more pressure on key resources such as land, water, food, and energy. Land is important as more than 40 per cent of our workforce is engaged in agriculture. But our arable land is getting degraded and holdings are getting smaller as farms nearer to cities and towns make way for highways, buildings and other projects. Land degradation extracts a heavy cost. According to a government-backed study by Pia Sethi of TERI, land degradation has led to a roughly 2.5 per cent loss of the country’s economic output between 2014 and 2015 alone.

Failed policies?

Many social scientists have expressed concern over the inability of our economic policy planning to generate adequate decent jobs. With land holdings shrinking and income from farming coming down, this is fuelling social friction, as jobless youth seek refuge in quotas (as there are not enough government and private jobs to turn to) and ruling politicians pander to this demand.

Parties of all stripes have historically extended backward-caste status to dominant castes even though they know it is unconstitutional. They find it politic to legislate unwarranted quotas and then leave it to the courts to strike down these quotas as unconstitutional. Quotas are becoming the new freebies.

In a bid to breach the BJP’s Hindu vote bank and split it into various sub-castes, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has now coined a new election slogan Jitni abadi, utna haq (the rights of any group are proportionate to its population share). He has also supported a fresh caste census and demanded that the report of the socio-economic caste census (SECC) of 2011 be made public.

-

Modi: BJP is cashing in on his surname

Moving beyond castes and ethnic groups, the demand for quotas is knocking at the doors of the private sector as well. As India strives towards the position of the world’s third largest economy (from its current fifth largest economy status), the emerging fault-lines pose a danger to our economic trajectory. India Inc, which has been facing flak for not generating enough jobs for our youth, has now to deal with private sector job quota laws being enacted by some state governments.

Private sector quotas

One such law came into effect recently in Haryana, which made it mandatory for the companies and industrial establishments to hire 75 per cent local candidates, who had a domicile certificate, for jobs having a gross monthly salary of Rs50,000 or less. After the law was termed regressive by India Inc, the state government tried to placate the industry by bringing down the upper limit of gross monthly salary to Rs30,000. A set of exemptions were ordered for start-ups, as also information technology (IT) and IT-enabled services.

Reservation in private-sector jobs will have both instant and long-term repercussions. At the surface level, it clearly violates Article 14 of the Constitution, which talks about the right to equal opportunity in matters of public employment. Similarly, Article 19 grants all citizens the right to freely move throughout India, to reside and settle anywhere, and to practise any profession or carry on any occupation, trade, or business throughout India.

The Haryana Act is also a direct attack on the fundamental idea of the Indian economy as one unit. On the one hand, where our Prime Minister talks about ‘One Nation, One Everything’, businesses – both domestic and multinational – may struggle to find skilled workers in states where the ruling parties are resorting to such short cuts.

Other states

Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh have also enacted laws requiring locals to be given preference in private jobs. However, each had to overcome its own set of obstacles, ranging from constitutionality to compliance. Andhra Pradesh was the first state to enact such a law in the face of rising unemployment in 2019, but it was challenged in the High Court there. Karnataka too passed such laws, most recently in October last year, asking the private sector to give preference to local candidates, but companies did not know how to ensure compliance.

Madhya Pradesh too has promised to bring in a 70 per cent private sector job reservation quota for locals. In August last year, Maharashtra too joined the bandwagon and announced that it would make it mandatory for the private sector to reserve 80 per cent of its jobs for local residents only. (However, since then, Deputy CM Devendra Fadnavis has backtracked from his statement.)

The demand for caste-based quotas has also found salience in the last few years because of farmer distress in the countryside due to agrarian crisis. The forward castes want the benefits given to other backward classes (OBC) category, so that they can shift away from agriculture. With opportunities shrinking in towns and cities, they feel that the only option left for them is government jobs. But, as acquiring normal government jobs entails stiff competition, they are asking for reservation.

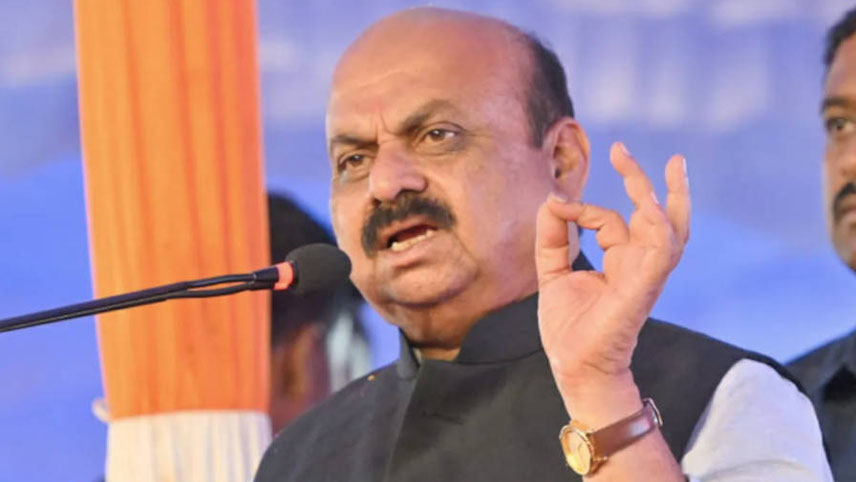

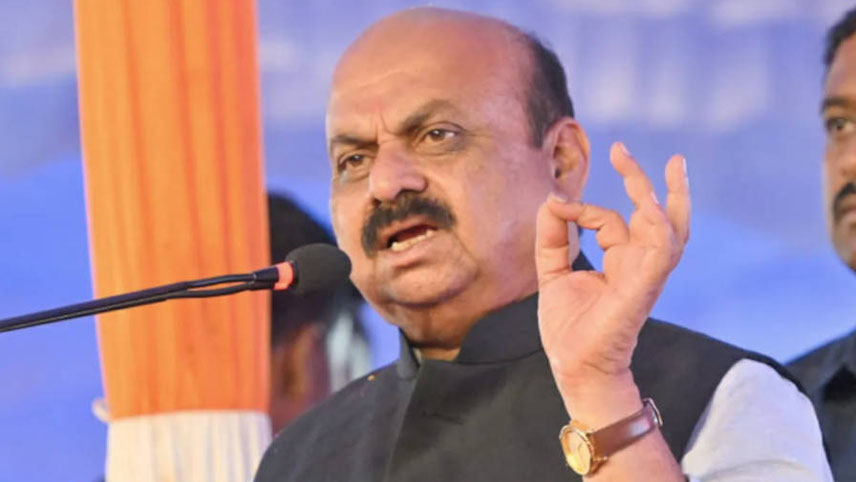

-

Bommai: his caste rejig failed

Statecraft involves management of competing demands for accommodation and inclusion, without unduly affecting the interests of any section of society. However, most ruling parties in the states have chosen to tinker with the caste quota policy in government jobs and education to garner political gains. In Karnataka, for instance, the BJP’s outgoing Basavaraj Bommai government, recently scrapped the 4 per cent quota for Muslims within the OBC category and earmarked an additional 2 per cent each to the dominant Vokkaliga and Veerashaiva-Lingayat communities in the expectation of electoral dividends.

The BJP regime also created four sub-categories to introduce internal reservation for different Dalit communities under the Scheduled Caste (SC) category. The scrapping of reservation for Muslims, whose poorer members will now have to compete with the general category for the 10 per cent ‘Economically Weaker Sections’ quota, is reminiscent of the abrogation of the 5 per cent quota for Muslims in Maharashtra in 2015.

What Constitution says

The Constitution does not allow reservation on the basis of religion alone, and that there have been judicial verdicts striking down quotas for Muslims for not being backed by a proper study on the extent of backwardness in the community. However, it is possible to extend reservation benefits to the backward sections among religious minorities identified on the basis of relevant criteria.

Some states have been implementing reservation in educational institutions as well as public employment for Muslims by including them in the Backward Classes (BC) list. So, while reservation on the basis of religion alone is untenable and debatable, in this case there was no recommendation from the Karnataka State Backward Classes Commission for the withdrawal of reservation benefits for Muslims. The BJP, of course, has sought to portray the introduction of reservation for Muslims in 1995 as an instance of minority appeasement.

While Muslim leaders and organisations opposed the scrapping of the reservation, sections of Dalits were also up in arms against the re-categorisation of the 17 per cent quota for SC communities in Karnataka. It is clear that major decisions, such as changing the reservation policy, in the run-up to elections are not merely suspect, but end up stoking unwanted controversies.

The Congress, mounting a strong challenge to the BJP, too jumped into the fray. A fortnight before the polling, Congress leader and former Chief Minister Siddaramaiah said that his party is ‘committed to increasing the reservation limit from 50 per cent to 75 per cent, and to increase reservation to all castes based on their population’. Karnataka already has a 66 per cent reservation, including 10 per cent for those under the economically weaker section (EWS) quota.

Focus on Manipur

The situation has got more exacerbated is Manipur due to its topography and population. The Imphal valley, which is home to Meiteis, covers just about 10 per cent of the state’s territory. However, it’s home to about 67 per cent of the population and also accounts for about 50 per cent of the cultivated area. The hills of Manipur, home to Kukis and Nagas, are largely forested. Forests cover a little over 75 per cent of Manipur. Across that area, hill tribes practise shifting cultivation.

Against this backdrop, dissonance between two other features of Manipur have put more pressure on pre-existing differences. First, the state has a separate judicial and governance system for the tribal hill areas, which are controlled by Autonomous Hill Councils. Second, these councils are authorised to manage and transfer property.

-

Haokip: leading the Kuki rebellion

In Imphal valley, Meitei groups’ clamour for reclassification as STs got a boost when the Manipur High Court directed the state government to submit a recommendation to the Central government on its demand for reservation. This was the immediate trigger for the recent violence, as Kukis feared the development would hit their prospects.

Currently, the Meiteis cannot buy land in the Hill Areas as the tribal land there is protected by Article 371C of the Constitution and its accompanying notifications. This is one reason the demand of the Meiteis (to be classified as STs and avail of the 7.5 per cent quota, when they are already enjoying 27 per cent OBC quota) is being viewed with suspicion by the Kukis.

Like elsewhere, jobs are difficult to find in Manipur. The structural economic pressures at play in Manipur were brought out in a central government report on employment of 2021-22. In Manipur, 42 per cent of the total households are in to agriculture. The lack of opportunities is apparent in the data as 60 per cent of the households are categorised as self-employed, a proportion higher than the national average of 54 per cent.

Knee-jerk response

So, when violence, arson, and mayhem rocked various districts of Manipur, including Churachandpur, Imphal East, Imphal West, Bishnupur, Tengnoupal and Kangpokpi early this month, its wasn’t totally surprising. The violence began on 3 May, after the All Tribal Students Union Manipur (ATSUM) held a solidarity march in all districts opposing the recent Manipur High Court order. Reacting in a knee-jerk fashion, the Manipur government issued shoot-at-sight orders.

Convoys of trucks belonging to the Army, the Assam Rifles, the Rapid Action Force, and local police personnel moved into the affected areas. As authorities struggled to control the situation, despite the flag marches conducted by the Army, mobile data and broadband connections were suspended. On 4 May, as the violence escalated, the Centre invoked Article 355 of the Constitution, which is a part of emergency provisions. It empowers the Centre to take necessary steps to protect a State against external aggression or internal disturbances.

Initially, the chief minister’s plea for calm proved futile. Suggesting that the violence was the result of a misunderstanding, Biren Singh said that the government was taking all measures to maintain law and order, including requisitioning additional paramilitary forces. Central and state forces were directed to take strong action against individuals and groups found engaging in violence. Indefinite curfew was imposed in the Meitei-dominated Imphal West, Kakching, Thoubal, Jiribam and Bishnupur districts, as well as in Kuki-dominated Kangpokpi and Tengnoupal districts. The affected people were shifted to safe homes or shelters.

Underlying anger

While the immediate provocation for the ethnic unrest appears to have been the Meitei demand to be included in the ST list, underlying anger had been simmering for a long time against the government’s clampdown on reserved and protected forests in the state’s hill areas. The Kukis were feeling persecuted. Several Chin, people of the same ethnic group from across the border in Myanmar, have entered India, fleeing violence and persecution there, and the state government’s tough stance against these so-called illegal immigrants has angered the Kukis, whose kin they are.

-

Fadnavis: backtracked on quota for locals

The BJP CM’s tough stance against what he calls encroachment of reserved and protected forest areas in the hills of Manipur by tribal communities stems from various causes, including the fact that many acres of land in the hills are being allegedly used for poppy cultivation. The government sees its crackdown on forest areas as part of a bigger war against drugs, but it is also guilty of using ‘drug-lords’ as a blanket term against all Kuki people.

Secondly, there is serious pressure on land in Manipur. As populations increase in the tribal villages, they are spreading out into surrounding forest areas, which they consider their historical and ancestral right. This is contested by the government. Simultaneously, the Meiteis, who live in the valley, are angry because they are not allowed to settle or buy land in the hill areas, while tribal people can buy land in the valley.

No policy

The problem is that the Manipur government has no real policy about how it plans to recognise new villages. Nor is there any transparent forest policy in Manipur. This has led to resentment even within the ruling BJP. Paolienlal Haokip, a vocal BJP MLA from the Kuki community, who is leading the Kukis’ rebellion against Biren Singh, has questioned the state government’s push back against tribal people’s protests over expanding reserved forests. Singh has said that his government is using satellite mapping to learn about changes in forest compositions in the hill districts and that they take encroachments seriously and would deal with it accordingly. According to Singh, anybody who protests against this goes against the Constitutional provisions, which provide for protecting forest lands.

The Centre has so far backed Biren Singh’s stand. During a recent visit to Manipur, Bhupender Yadav, Union Minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, asserted that, while the 1927 Forest Act had become a ‘state’ subject after Independence, after the 1976 Amendment, forest land came under the jurisdiction of both the state and Central governments. The state government retains ownership of the forest and was solely responsible for protecting reserved and protected forest land, he added.

Meanwhile, as tensions continue to simmer in Manipur, there appears be no respite in the offing. Caste-based reservations were meant to correct historical injustices with a sunset clause. What happened to this clause? Shouldn’t the idea even be debated? Are we saying that 75 years after Independence, we have failed completely to create a society with equality of opportunity that each year we have to pass laws asserting that merit cannot be the only criterion for advancement; that we still have to come up with special quotas?

SC ruling on EWS

It is imperative to restart the debate as the Supreme Court judgment on the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) quota in December not only reaffirmed the principle of reservation but also suggested that it’s no longer necessary to cap it at 50 per cent. This means that the majority of jobs and seats at educational institutions will not be in the reserved category. Also, governments can go beyond caste and reserve jobs and seats on the basis of economic status.

-

Siddaramaiah: committed to increase the quota limit

The judgement came with a dissenting view by former Chief Justice of India U.U. Lalit and Justice S. Ravindra Bhat, who said that the extension of quotas was ‘contradictory to the essence of equal opportunity’ and that it ‘struck at the heart of the equality code’. However, since the Supreme Court was not discussing caste-based reservation and the case had to do with an extension of reservation to EWS, these were two significant issues to be considered.

But the judgment has raised two disturbing issues. Could the quantum of reservation go above 50 per cent of available opportunities? Yes, the judgment of the majority suggested. And, was it okay if this extension excluded those covered by other quotas? The majority said ‘yes’ again.

The judgment, it was said, represented the political consensus of the day. Besides, the Supreme Court was not asked to consider is a more crucial question: Is the regular extension of reservation based on a need to level the playing field?

Clearly, quotas just become yet another way for politicians to appeal to vote-banks to secure their support. At every election, you will find politicians promising further reservation if they are elected. Every party does it at some level. Just as politicians dole out material freebies (or revdi as Modi has called them), they now offer reservation in the hope of winning votes.

What is significant is that even the BJP, which was so worried by V.P. Singh’s Mandal announcement, is now playing the caste game. It frequently draws attention to Modi’s ‘backward’ caste and wins elections by constructing caste coalitions – whether they work or not (as in Karnataka) is another thing. Quotas for EWS is being glibly passed off as welfarism.

Meanwhile, the quest for an India where caste would not matter has been abandoned. With reservation, citizens need to know exactly what caste they belong to – and this may continue for generations to come.