-

Many states have toned down their labour regulations on issues like worker safety, rights and working hours to get the industry going post-lockdown

Modi gameplan

Reworking his ‘Make in India’ initiative, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has now conjured up a plan to play a major role in the global supply chain (GSC) by wooing global mobile handset makers, consumer durable companies and others willing to put out more than half a billion dollars. On offer are tax incentives, easy access to land and other infrastructure.

Modi has asked chief ministers to double up in their effort to attract investments from global companies that might want to exit China.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s stimulus package, which has provisions to let states borrow beyond their 3-5 per cent limit, comes with a caveat that this flexibility will depend on how the states perform, from sustainability of the debt to attracting investment and improvement of urban infrastructure. The states of Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have set up task forces to attract firms keen to leave China.

Many states have toned down their labour regulations on issues like worker safety, rights and working hours to get the industry going post-lockdown. These desperate moves have come in the wake of the massive reverse migration of labour to villages that one saw after the outbreak of Covid-19.

Ironically, these are the very issues many conscientious MNCs in western democracies are particular about these days for fear of a public outcry. Mistakenly, this has spawned hopes of wider labour reforms and that other states will soon follow, competing to draw foreign investment. Also, that rivalries between states will drive deregulation further when politics prevents this from happening in New Delhi.

-

As an ongoing exercise, India is readying a pool of land twice the size of Luxembourg – a total of 461,589 hectares is believed to have been identified across the country – to offer companies that want to move manufacturing out of China. The government has also reached out to 1,000 American MNCs. Deepak Bagla, chief executive of Invest India, the national investment promotion agency, says that “Covid will only accelerate the process of de-risking from China for many of these companies.”

But will it work?

India needs to act fast. “If India can make like-for-like replacement possibilities, make land and electricity available and all clearances are in place to (help companies) de-risk on a permanent basis, it is an opportunity. The government has helped with 15 corporate tax rates. If we now get to the administrative side to offer a plug-and-play model with our advantages, it is an opportunity for us. But we have to be faster and better than other competing countries,” says Hitendra Dave, head, global banking and markets at HSBC India.

Also, foreign companies would like to see more action on the ground before moving in. For one thing, things are still at an evaluation stage and decisions are unlikely to be made in a hurry. In an environment where global balance sheets are fractured, relocating entire supply chains is easier said than done. As economist Rupa Subramanya points out, many of these companies are facing severe cash and capital constraints because of the pandemic, and will therefore be cautious before making quick moves.

In any case, it’s not going to be a cakewalk. While there might be one high-profile case of Apple deciding to invest one billion dollars in manufacturing iPhones in Hyderabad, there are many others wanting to leave China, but not to India. According to a study by Nomura, out of the 56 companies that shifted manufacturing out of China between April 2018 and August 2019, only three had chosen India. Almost half of the businesses chose Vietnam. Even Taiwan and Thailand ranked higher than India.

-

Agro advantage: India is among the top producers of many agricultural products. Photo Credit: Sanjay Borade

The reason is not far to seek – ease of doing business. India is a lowly 63rd in World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business’ index, though the Modi government has never stopped advertising from the rooftops how much India has improved in recent years – that it is among the top 10 in countries racing up the ranks. Yet, fear of India’s bureaucratic red tape, complicated system of getting clearances, and constant tweaking of rules and taxes continues to scare away potential investors.

The steady decline in the value of the rupee is another genuine dampener for FDI. Since profits are recorded in foreign currency, like the yen or dollar, each time the rupee declines, it erodes profitability of the investor. One reason the rupee is weak is because of lack of growth in exports.

China’s advantages

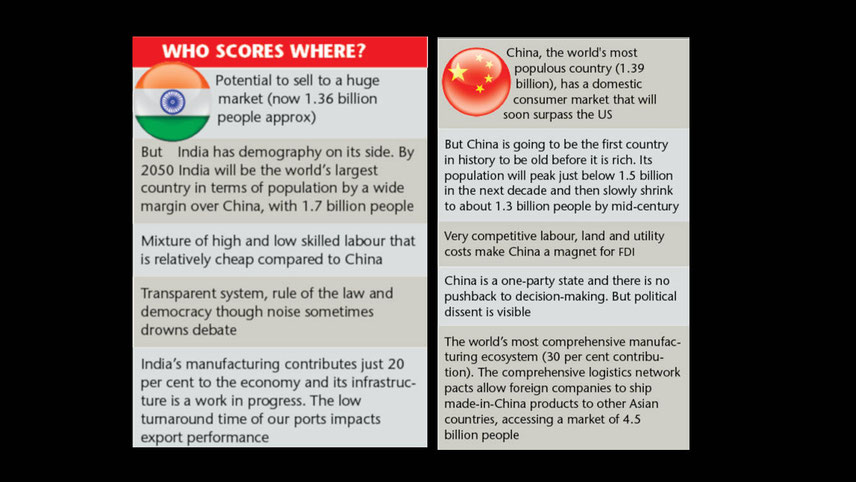

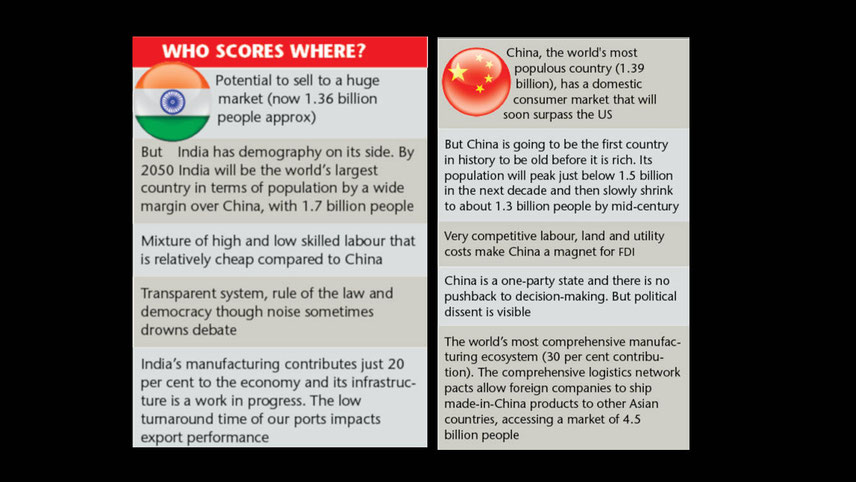

Indeed, India will have to push really hard to compete with China, given the latter’s fabled development norms. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report bluntly states that India lags China in every infrastructure category. In terms of GDP, India invests about 30 per cent of its GDP, compared with about 50 per cent in China. Manufacturing constitutes about 20 per cent of the Indian economy; it is about 30 per cent of China’s.

Outside the West, China has arguably the best physical infrastructure consistently built over the last four decades. These include the world’s largest expressway and railway networks, and seven out of the world’s top 10 cargo-ports. Infrastructure development in India, particularly road development, got a leg up after Nitin Gadkari took charge of this ministry. But it is still a work in progress. India is struggling to build world-class infrastructure that could make it as competitive. China has planned its hubs in such a way that businesses and their suppliers are close to each other, something that helps save time and transport costs.

-

The Chinese investments run into Rs5,000 crore, led by Great Wall Motors which will set up a Rs3,700-crore automobile plant in Maharashtra

Then there is the issue of labour. Indian labour may be cheaper, perhaps even more hardworking but Chinese labour scores on productivity. The contract labour system gives their foreign employers the leeway to hire and dispose of labour as the situation demands. India has a huge population of migrant labour but no databases or even a mechanism to effectively channelize this strength.

Once the lockdown is lifted and the Covid-19 situation gets back to some semblance of normalcy, the government must target the newly relocated migrant labour populations with skills training, and skill transfer programmes that could help cultivate a re-enabling platform for them. On a parallel plane, they should be targeted with social security and healthcare schemes.

Economists and Nobel laureates Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee have rightly argued for the employment of the JAM (Jan Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile) scheme to transfer money into their bank accounts. Such steps will inject liquidity into the market, more importantly it will be the building block of any gameplan to attract foreign investment two-three years later, if not now. In targeting foreign investment and becoming a GSC, India needs to keep in mind the indispensability of China in the global as well as our economy.

This became clear as daylight last fortnight in Mumbai, when chief minister Uddhav Thackeray signed agreements for foreign direct investment (FDI) worth Rs16,000 crore under Magnetic Maharashtra 2.0, a virtual dialogue organised by the CII. Interestingly, just when several trade and industry organisations were calling for a boycott of Chinese goods, three Chinese companies figured prominently in the 12 companies which signed Rs16,000 crore worth of MoUs. The Chinese investments run into Rs5,000 crore, led by Great Wall Motors which will set up a Rs3,700-crore automobile plant in Maharashtra. This was hours before the violent faceoff between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley, Ladakh.

-

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee: use JAM scheme to transfer money to people. Photo Credit: TheIndianExpress.com

It is only after the public outcry against China and the Centre’s prodding that Maharashtra has now frozen the three MoUs. But the development highlights how smoothly the Chinese firms have got integrated into our economy. Some experts fear that denying Chinese firms a foothold in our markets, as a measure of reprisal, without getting commensurate and compensatory investment from elsewhere, could be a self-defeating idea leading to loss of jobs, among other things.

Surely India will not become a manufacturing power in one year, nor will it be blessed with the requisite infrastructure and supply chains during this short period. Nor will the much-vaunted shift from China take place overnight.

Take the case of German footwear brand Von Wellx. Much has been made of the company’s plan to shift its manufacturing base from China to Agra in UP. The fact, however, is that this company was already outsourcing its products to shoemaking businesses in Agra.

China plus 1

Indeed, the government’s new thrust will need to be properly nuanced. After all, you are competing with China where “the comprehensiveness of the ecosystem, coupled with an abundant supply of low-cost, highly educated workers, is a key reason global firms manufacture sophisticated products, such as electronics, in China,” as Aidan Yao, senior emerging Asia economist, AXA Investment Managers, Hong Kong, points out.

-

Auto manufacturing: India is the world’s fifth largest market. Photo credit: Sanjay Borade

Yao notes that anecdotal evidence suggests that some US companies have started to adopt a “China plus 1” strategy: moving only a fraction of their supply chain to a third country that serves as a backup option. But the Chinese government is not sitting by and watching its advantages slip away.

Already, the trade war with the US has forced Beijing to accelerate reforms on multiple fronts, including opening up previously monopoly industries, strengthening protection of intellectual property rights, and shortening the foreign investment “negative list”. These moves that could make the Chinese market more accessible and ease foreign firms’ concerns over unfair competition.

China plus 1 has been the new post-Covid buzzword among investment managers for some time now. Businesses adopt the model to reduce operating costs, diversify workforces and supply chains, as well as access new markets. Businesses that adopt the strategy become less vulnerable to shocks like supply chain disruption, currency fluctuations, and tariff risks. They can quickly scale up one country if market or operating conditions deteriorate in the other.

Even in the pursuit of this model, India will have to compete with many nations, including the new ASEAN tigers, Vietnam and Cambodia. China could even prop up Bangladesh, where it is making heavy investments, as a surrogate competitor to India.

Atmanirbhar what?

In his address to the Confederation of Indian Industry’s annual session, Modi tweaked his as yet half-baked concept of ‘atmanirbhar’ (self-reliance) to say that it implies that goods ‘made in India’ should also be ‘made for the world’. This, on the face of it, is different from import substitution preached by successive Congress regimes, starting with Nehru. It possibly implies that India needs a larger domestic manufacturing base that is globally competitive, so that what is made at home can be sold abroad.

-

The current crop of chief ministers has little incentive to push forward more wide-ranging deregulation because it would reduce their own power or rent-seeking ability

However globally, there is an air of export-pessimism today, on account of rising protectionism, the paralysis of multilateralism in trade, and the post-Covid disruption of maritime trade. Will this depressing global scenario jell with Modi’s ambition? Also, Modi has over the years rejected multilateralism (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership being the latest example) and thus denied India the framework and opportunity, including the supply chains, to emerge as a major exporting power.

Modi’s plan will need more fleshing out, instead of simply inviting FDI and asking domestic producers to ‘make for the world’. If he is looking at the southeast Asian model, then he must remember that these countries have pursued a strategy of promoting import-dependent export growth. The global supply chain based trade contributes to an increase in exports and to export-related imports.

Can states rise?

As for the states, which will presumably be the new engines of growth in Modi’s scheme of things, they will have to get their act together. In the past, where states have attracted investments, it’s usually been due to influential chief ministers, who could remove regulatory roadblocks on a case-by-case basis.

Thus, foreign investors came to rely on state leaders such as Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra Pradesh, late Jayalaltihaa or Karunanidhi in Tamil Nadu or even Modi in Gujarat. However, the current crop of chief ministers has little incentive to push forward more wide-ranging deregulation because it would reduce their own power or rent-seeking ability.

-

Amitabh Kant: regulatory cholesterol under control

While Sitharaman’s incentives will help, the only permanent solution to this problem is to allow state governments more control over their finances. That should eventually translate into greater freedom over their own policies.

While this is naturally difficult during an economic slump, two changes would make an immediate difference: first, increasing the states’ share of total revenue; and second, reducing the number of national welfare and subsidy programmes in order to give states control over those resources. Only when they no longer have to look to New Delhi for their financial survival will states really be free to compete with one another.

All this will take time. Instead of putting too much on its plate, Modi should capitalise upon proven areas of strength, where too much investment or effort may not be required. India has frittered away too many opportunities in the past. These should be reclaimed.

Kotak speak

Uday Kotak, who has taken over as president of CII, recently expressed the view that if China can be the factory of the world, then India can surely be its office. “Why should Google pay $200,000 to work-from-home US engineers, when they can cheaply hire Indians here to do the same job on VC. Same with finance analysts, marketing, architects etc. New world creates new opportunities,” Kotak had tweeted.

The tweet drew flak from twiteratti who criticised the banker for his “cheaply hire Indians” comment. The Kotak Mahindra Bank chief later clarified his earlier tweet stating that his comment was based on the difference in “purchasing power parity”.

Later, Kotak said: “If we are to become the ‘factory of the world’.which is what China has been, we must try. But that does not preclude us from becoming back office. Work from home has taught us that we have the opportunity to also become the office to the world. Be it in California or in a village in India, if a worker has the skill required in the new post-Covid world, he can be operating from anywhere in the world and be hired by anyone, from Google to Jio. You don’t need to be the back office; you can be the front office of the world, and, without in any way upsetting our game plan of Make in India. Ideally, we should be both the factory and the office of the world.”

-

A need for investments in R&D. Photo credit: Sanjay Borade

Back office hiccup

Till the Corona virus struck, India was humming along well as the back and middle office of the world, thanks to our educated young men and women with high computer skill-sets and high proficiency levels of spoken and written English. India’s $181-billion outsourcing industry which handles everything from trade settlements and airline reservations to insurance claims and bank queries had been making a mark for itself over the years.

But this industry was administered a shock by the pandemic and the government’s hasty effort to counter it via a series of lockdowns. When the first phase of the Corona virus lockdown was announced in March, the thousands who staff the back offices of Wall Street banks and take on outsourced work were scrambling to get their act together.

Initially, according to industry sources, the lockdown effectively closed call centres and other units overnight, without a warning. UBS Group AG, Deutsche Bank AG and other global giants then appealed to industry trade group Nasscom to ensure that the state governments classify such work as essential services so staff can continue to work from offices if required.

As part of the business continuity in this critical situation, companies like TCS and Infosys enabled work from home for large number of its employees. Millions of desktops and laptops were moved to employees’ homes and software was configured to allow for slower bandwidth and ensuring cyber security.

Apart from restrictions on transport and for social distancing, the fear of getting infected was another factor that deterred the staff from coming to office or the managements from pressing for attendance. Even though the government’s rules for lockdown extension later permitted offices to host one-third of staff strength, most white-collar working spaces remained empty till recently.

-

European regulators have also assessed the impact of India’s lockdown on the banking industry which exposed the challenges of providing the infrastructure required to work remotely

Such disruptions can be killing – and should be avoided in the future as they can reverse some of the wave of outsourcing that moved back- and middle-office jobs to India. While state governments including Karnataka and Maharashtra were quick to grant special exemptions so that some employees could go to offices, those policies were not across the board. Some of the largest securities firms like JPMorgan Chase & Co, Barclays Plc and Nomura Holdings Inc grappled with a sudden halt of their back office operations in India. Some banks transferred work usually done in India to other countries.

Indeed, some global banks are now even scrutinising their presence in India. European regulators have also assessed the impact of India’s lockdown on the banking industry which exposed the challenges of providing the infrastructure required to work remotely. The push to outsource support functions such as call centres “exposed these banks to operational risks”, according to a European Banking Authority report accessed by Business India. “Many such offshore facilities were less prepared to address the Covid-19 operational challenges owing to a lack of opportunities for remote working or reduced availability of staff,” the EBA said.

Since this is an established area of strength, India should not be sanguine about the mis-steps that it recently took. Having failed to prep up the industry for what lay ahead, it should not repeat the mistake.

Automotives goldmine

In the flurry of announcements made last month, Sitharaman also borrowed a move out of China’s playbook – the plug-and-play model. However, as Biswajit Dhar, trade economist and professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, points out, at a time when the economy is facing massive challenges with a plummeting GDP, “one cannot do things in a hurry; cannot plug and play”.

-

R&D: a weak link. Photo credit: Sanjay Borade

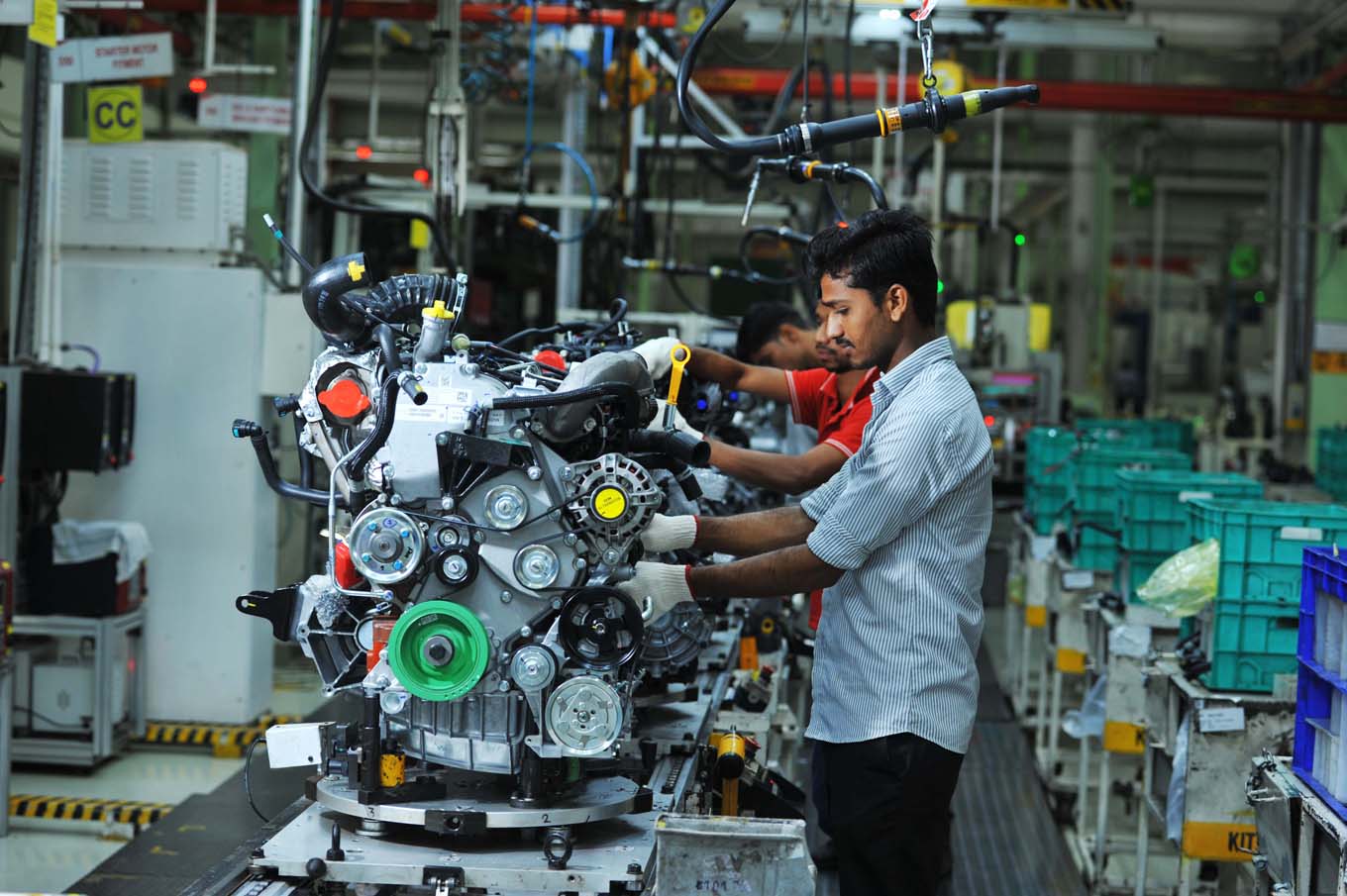

However, sectors such as auto manufacturing (India is the world’s fifth largest market) and a components ecosystem, are typical of industries incubated in an earlier phase of reform that have grown to world-class scale and quality, and today are a plug-and-play for incoming foreign manufacturers.

R&D hub

Another area with great potential is Research and Development (R&D). Any economy that has self-reliance as its goal must commit itself to make policy shifts and invest heavily in R&D.

But ever since the onset of liberalisation, two distinct trends have manifested. Our PSUs, which were tasked with R&D work, never got their act together. Many nascent R&D efforts (in photovoltaics, semi conductors and advanced materials, to name a few) were abandoned. With the entry of foreign corporations, the private sector retreated into technology imports or collaborations.

As a result, India’s gross national expenditure on R&D is just 0.7 per cent of GDP. Amongst developed economies, Israel spends 4.4 per cent, Germany 3 per cent, the US 2.8 per cent and Canada 1.6 per cent of their GDP on R&D. Our share of expenditure in higher education is even lower.

V.K. Saraswat, former secretary, Defence Research and Development Organisation, and now member, NITI Aayog, has called for higher public investments in the overall R&D sector, which should at least target 2 per cent of the GDP. “Then only we can see a substantial increase in our innovation, in our Intellectual Property Rights and in our economic growth. IP rights, innovation and competition are the main factors which are responsible for economic growth. The balance between IP and competition will certainly foster more innovation,” he added.

-

Uday Kotak: we should be both the factory and the office of the world

This will augur well also both for our scientific establishments and MSMEs that require cutting-edge technology to prosper in a competitive global environment. Currently, our R&D presents a paradox, giving rise to a third trend. While Make in India is yet to make headway in the manufacturing sector, some global companies are hedging their bets on India as the next frontier for research. They are coming here – and not for cheap talent, considering most of these researchers get paid at par with global standards.

For instance, IBM India Research Lab is as big as the first-generation labs in the US both in terms of size as well as the quality of work. Hundreds of patents and hundreds of scientific publications come from the lab every year. Cisco, another large R&D organisation in India, is investing $1.7 billion a year in India, largely into its 5,000-member strong R&D team in Bengaluru.

But while global firms like IBM, Cisco and Adobe may be beefing up their R&D work here, the fact is that the participation of foreign companies is limited to sectors like information technology, bio-technology and pharmaceuticals. Scant work is being done in core sectors like, say, steel or defence. Our R&D establishments are more into refining existing products. They are also grappling with a paucity of ideas for research as well as funds.

For instance, R&D and innovations are the weak link in steel industry in India – the reason why the Steel Research and Technology Mission of India was formed last year (as were the missions in other sectors under previous regimes). Private firms have spent relatively more than public sector steel firms which were mostly on an expansion spree. Our PSUs in other sectors are also lagging behind in the use of cutting edge technology, thanks to tardy R&D budgets.

To feed the massive growth of research work, we will need to have the right reservoir of talent. Our education system needs to be ramped up to cater to this market. Take the case of the steel sector. Most Indian colleges have civil engineering courses but not on vertical steel structure design – which is the new thing.

India needs several thousand of expert engineers to popularise steel structure construction. It is only now that the steel industry and its affiliate bodies are in talks with IITs to bring changes to the curriculum.

Clinical trials

India has almost killed the market for clinical trials where it could be the world leader due to overregulation. Stringent controls on the sector had driven the clinical trial industry out of India, with companies moving to Brazil and the US. While earlier India had 16 per cent share of the clinical trials market, this came down to almost 1 per cent.

It is only after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, when the need to boost the healthcare system became obvious, that the government pushed through critical reforms to cut down the regulatory maze for faster clinical trials and boost R&D as well as propel innovation in vaccines and therapeutics.

-

India is the third-largest producer of pharmaceuticals in the world by volume, and supplies an estimated 20 per cent of global exports of “generic” drugs

In a move expected to shave approval time for clinical trials to three months from the current 12 months, the government has designated the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) as the first point of registration for clinical trials of all drugs and vaccines.

“Regulatory cholesterol, which was severely impacting innovation in pharma and biotech sector, has now been addressed,” says Niti Aayog chief executive Amitabh Kant. “By streamlining regulatory pathways in CDSCO and ICMR, we have brought all institutions and regulators together through a series of meetings by Cabinet secretary and in Niti Aayog.”

World’s pharma

India could be the pharmacy to the world. The biggest pharmaceutical companies in the world are American and European, yet these companies – and the pharmaceutical industry as a whole – rely on global supply chains, and on China and India in particular.

To bring the pandemic under control – either through treatments such as remdesivir, the anti-viral the UK has announced can be used for the most acute cases of Covid-19 – or a future vaccine, the world depends on pharmaceuticals. And the involvement of China and India will be crucial if the pandemic is to be brought under control.

The pharma manufacturing supply chain involves two main stages. The first is the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) – the key parts of a drug which produce an effect. The second stage is a physical process known as formulations production. For more than a decade now, China has been the world’s largest producer of APIs. It supplies an estimated 40 per cent of APIs used worldwide.

India is the third-largest producer of pharmaceuticals in the world by volume, and supplies an estimated 20 per cent of global exports of “generic” drugs – that is, drugs that are no longer under patent. The country is also the major supplier of medicines to countries in the global south, leading aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières to dub it the “pharmacy to the developing world.”

India’s stature in the sector stems from the range and volume of medicines it is able to produce as well as the low prices it is able to offer. Indian pharmaceutical firms are the largest among Asian countries in their capacity to produce generic medicines. However, India’s stature as a pharma power lags a bit in developing new medicines.

-

Pharma companies face stiff competition from China

Also, our pharma companies face stiff competition from firms in China, Japan and Israel, and experience hostile behaviour and intense negative lobbying from ‘Big Pharma’ groups in the US which routinely accuse Indian companies of violating patent laws.

Then there is India’s dependence on Chinese APIs. India currently sources 70-80 per cent of APIs and key starting material for drug formulation from China because of cost viability. Companies like Granules India and Aurobindo Pharma have among the highest exposure to imports of APIs from China, with the latter mainly for antiretroviral and antibiotic drugs.

It is only now that the government has begun to fast-track a production-linked incentive scheme to increase production of raw materials in the country itself. The plans include identifying important ingredients used in medicines, giving incentives to local producers, and helping neglected state-run producers to regain some ground in the industry.

Pharma leaders believe that the government should adopt a graded strategy of providing credit and support to one section of the industry, for instance those who manufacture one type of medicine, then replicate it with firms that produce other medicines. Boosting the production of medicinal raw materials and medicines will counter China’s dominance in the global market. Hence, the coming challenge to India’s pharma production might also bear opportunities for India in terms of emerging as a self-reliant API-exporting nation.

Health tourism

Inter-linked with pharma is medical tourism, a sector that includes a range of medical services like dental care, cosmetic surgery, elective surgery, organ transplants and fertility treatment. Similarly, India could have been a leader for elective surgeries and transplants. It could have been a leader in medical tourism. Medical tourism in India was valued at around $3 billion in 2015, and it was expected to grow to $9 billion (growing at a CAGR of 18 per cent) in 2020 before Covid-19 struck.

While we are in a paradoxical situation where even our high profile desh-bhakt politicians, who otherwise make a fetish for doing things Indian, go abroad for minor organ transplants, India’s advanced facilities, skilled doctors and low-cost treatment make it an ideal destination for medical tourists. Aside from modern medical practices, India has also promoted traditional practices such as Yoga and Ayurveda that promote overall wellbeing and health.

-

Pharma leaders believe that the government should adopt a graded strategy of providing credit and support to one section of the industry

With the influx of tourists, including medical tourists, is expected to remain subdued at least for a good part of 2020 but it will pick up later. Here, the track record of governments in handling the pandemic will matter. “Medical tourists will probably be much more aware of where they go and how ‘medically safe’ the country seems to be to them, and medical travel destinations, like India, that have had a lower number of Covid-19 cases and fewer deaths relating to the virus, are likely to have a faster recovery,” says Piyush Tiwari, director (commercial and marketing), India Tourism Development Corp (ITDC).

Dr Harish Pillai, chair-FICCI medical value travel committee, adds, “As soon as the international air travel restrictions are lifted, medical value travellers, after following due protocols including RT-PCR testing, will flock to India simply for its value proposition of outstanding value for money and excellent clinical outcomes.” The government needs to step in by simplifying the visa application processes for medical tourists so that more people can seek treatment in the country.

Surrogacy market

While dealing with this sector, India will also need to take a fresh look at surrogate births which many view as a form of “health tourism”, aside from a social service of sorts (as it can provide the joy of a longed-for child to childless adults). India had legalised commercial surrogacy in 2002 but banned it in 2015. The issue of foreign surrogacy became controversial after the case of Baby Manji Yamada vs Union of India in 2008.

In this case, a child born to an Indian surrogate was left in limbo after the Japanese commissioning parents divorced before birth. Neither the surrogate nor the intended mother wanted custody of the baby. The commissioning father, who did want the child, was not allowed to adopt as a single person under Indian law. As a result, it was unclear who the legal parents were, and what the child’s nationality was. The custody of the baby was finally awarded to the baby’s grandmother.

The bill was made and passed with the intention of tightening the loopholes in the existing law and preventing exploitation of women. However, some of the clauses had both the medical community and the general public outraged. The bill exhibited a lack of understanding of the fact that a woman should be able to make decisions when the question is in regard to her own body. A women’s surrogacy was limited to only once.

Only a relative could become a surrogate mother. One of the most regressive points of the bill was its blatant ban on surrogacy rights of homosexual couples with Sushma Swaraj, the late BJP leader and Union minister, openly stating that surrogacy for homosexuals was against “Indian ethos”. This is the first time that the government’s transparent homophobia came out in the open.

-

India has also promoted traditional practices such as Yoga and Ayurveda

Critics of the bill pointed out that limiting a woman’s surrogacy choice to only once was in a significant way limiting the income of those who thrive on this business. Again, it comes down to the issue of consent. If a woman willingly consents to being a surrogate mother, is assured of a safe delivery; and the baby is assured of a safe home, why should she be limited to only one surrogacy?

After the surrogacy industry boomed, a lot of women were dependent on the same. So, instead of regulating the policy in which a woman’s exploitation is prevented, the bill totally eliminated the idea. And so with the passage of the bill, India effectively killed the market for surrogate births.

Then there is the market for retirement homes which India has yet to exploit. Many NRIs, facing challenging times in their present domiciles, are looking at creating a safe haven back home in India. Those who have faced challenges in terms of investments in paper market are also seeing the obvious advantage of shifting to real estate as the asset class of choice.

This is an opportunity Indian builders can cash in on. Otherwise too, retirement homes in winter would have been a hit with NRIs who want to escape the chill of Europe in winter. Yet our tax and exchange control laws have frowned upon the possibility in the past, driving NRIs away.

Farm advantage

Yet another opportunity for India is to become the ‘food factory’ of the world. India should capitalise upon its strengths and also its post-Covid revival strategy which gives a major thrust to agriculture and food processing. Since the first generation reforms, dwindling prospects in agriculture have capped economic growth by containing the overall demand.

-

The government now wants to create a unified market in agriculture commodities, pushing investment in agriculture supply chain through the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund

The government now wants to create a unified market in agriculture commodities, pushing investment in agriculture supply chain through the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund, better price realisation for farmers and bringing modern technology in agriculture. Thanks to the bountiful harvest this year, income generation through agriculture and allied activities will generate rural demand.

India is among the top producers of many agricultural products like milk, coffee, wheat, rice, sugar, fruit and vegetables. Yet, only one-tenth of produce is processed, yielding little value creation in either incomes or productivity and there is a huge potential to increase exports. Food processing is potentially a big employer, from small units at the farm gate to industrial size in tertiary processing. Announcements on pricing deregulation and financing processing infrastructure at the farm gate should help producer organisations and micro-enterprises.

India should deepen its international trade cooperation in agriculture by reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers, especially lowering trade barriers for inputs. At the same time, many distortions in agricultural markets on the national level should be addressed, like improving warehousing, infrastructure and cold storage. And India has to adapt its agricultural sector to different and changing climate zones.

Reclaiming growth

Having once overtaken China as the world’s fastest-growing major economy, with consistent growth of 8 per cent, India has seen its GDP growth fall to its lowest rate in the last 11 years. To challenge China, India first needs to sort out its affairs at home. This means not giving in to the temptation of protectionism, choosing instead to work on structural reforms that make it more competitive. It means strengthening infrastructure and supply chains to attract more business.

India must try to aggressively acquire a higher share of global trade. If it is not careful, much smaller countries will further chip away. For instance, while in November 2019, India refused to join the RCEP. This FTA, as it turns out, concerns a region that is least affected by Covid and most likely to see high trade volumes in the future. In contrast, Vietnam signed an FTA with the European Union earlier this month. Indian exporters were already losing ground in the EU to Vietnam will now be adversely affected since most Vietnamese goods will enjoy zero import duties in the EU, thus making them more affordable for European consumers.

India has the potential for change. The challenge remains to find better ways to catalyse it. The potential is huge. But those who are calling the shots will have to first see it. Before aspiring to become a global supply chain, India should capitalise upon its inherent strengths. This would be a more practical way to get things going.