-

Multiple benefits notwithstanding, there are, however, pertinent points which some observers are raising saying these should not be glossed over in the rush of things. To begin with, does the proposition mean encouraging water guzzling crops like sugarcane and paddy at a time when diversification in horticulture at a large scale is the advised panacea to deal with underground water recession?

Sugarcane and paddy alone are estimated to consume 65-70 per cent of the water used in crop cultivation in the country. Secondly, the kind of aggressive targets which the government has set, and which entails more than doubling ethanol production in the next three to four years – will all this not need the creation of adequate storage and distribution infrastructure across the country on a war footing?

So far, the infrastructure created in ethanol production is mainly concentrated in a bunch of four to five states, which lead the pack in sugarcane production in the country. Another critical issue is: will the simultaneous and more highlighted emphasis on electric vehicles in recent years create some confusion in the marketplace, especially for automobile manufacturers? “I would say the big-ticket ambitions they have shown for ethanol is not misplaced,” observes RS Sharma, an oil industry veteran & former chairman, ONGC. “For the country’s energy security and its environment preservation commitments, the government is working with all available tools in transportation – CNG, LPG, e-vehicles and now giving the green signal for the adoption of ethanol at a large scale. There is nothing wrong in this approach as ethanol has proved its efficacy in some of the leading economies.”

Momentum in recent years

To some, the idea of pushing ethanol to an inflection point by the NDA government actually means furthering something which was initiated by another NDA government about 20 years ago. The idea was backed by the then Petroleum Minister Ram Naik in the late Atal Behari Vajpayee government (1999-2004). “By the time India decided to adopt this, ethanol had already proved its potential in some important global pockets. And it has a long history,” emphasises Pramod Chaudhari, chairman, Praj Industries, a leading firm in bio-based technology, headquartered in Pune. “It was selectively used as a fuel in the Second World War and also in some African countries. But it was the success of Brazil in 1973-74 in using ethanol after the first oil price shock, which compelled the world to take note of its usage as a fuel supplement. Later in the 1980s, the US also took it up aggressively, using corn as the feedstock, unlike the sugarcane used in Brazil. In the 1990s, a leading international agency certified ethanol as a clean fuel and, since then, it has been on a roll,” he explains.

According to Chaudhari, ethanol’s debut in India was on a low-key basis, which did not show any signs of increasing in size in the first decade of its use. “On 1 January 2003, a pilot test was done for 18 months in nine states and four UTs. It was, however, not pursued seriously later and could not pick up much momentum with most of the provisions for it coming more in the form of recommendations rather than being made mandatory initially,” he underlines.

Abinash Verma, director general, Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA), feels no differently. According to him, the first decade of ethanol production was marked by various policy flipflops, with the oil marketing companies reluctant to aggressively play their bit in the creation of capacity. The cyclical crash in sugar production in 2009-10 also played a key role in low action as the stakeholders were more concerned about meeting the demand for the commodity. But since 2014, as Verma vouches, there has been a marked change in the scene.

“This government has clearly shown a commitment to put ethanol blending on a growth path through gradual moves and I would cite three turning points since 2014. Firstly, announcing a fixed pricing policy for ethanol in December 2014, followed by the unveiling of the new bio-fuel policy in 2018, which facilitated the usage of stock feeds other than sugarcane for ethanol production on large scale. And then came the incentivising creation or enhancement of distillery capacity through the interest subvention scheme, which included grain-based units,” Verma points out.

-

Chaudhari: ethanol got a low-key debut in India

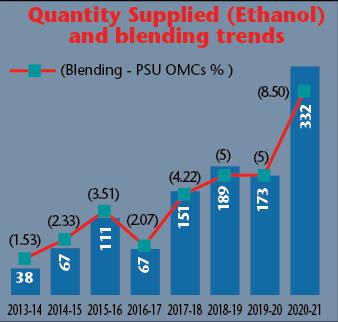

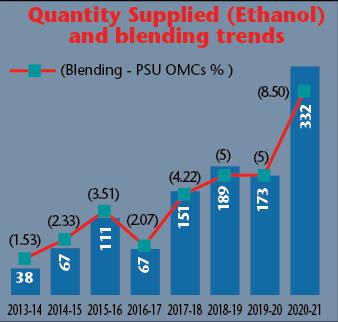

A report submitted by an expert committee of NITI Aayog (unveiled by the Prime Minister on the occasion of World Environment Day) titled: Roadmap for ethanol blending in India, 2020-25, provides enough statistical support to underline the point that the ethanol story has grown at a noticeable pace in recent years. The report points out that the supply of ethanol has increased from 380 million litres during 2013-14 to 3.32 billion litres during 2020-21 (see graph: Quantity supplied), resulting in increase in blend percentage from a meagre 1.53 per cent to over 8 per cent now.

The NITI Aayog paper highlights a series of moves which have assisted in the expediting ethanol growth story. It also includes expediting environmental clearance to the projects. “Now, the environment clearance of the distillery projects takes half the time it used to earlier,” Verma testifies.

The announcement of the two interest subvention schemes (in July 2018 and March 2019) is believed to have given a major boost to sugar manufacturing units to upscale their distillery capacity. According to the report, loans amounting to about Rs3,600 crore have been sanctioned by banks to 70 sugar mills so far. Furthermore, the Ministry of Food had invited fresh applications (30-day window) last September for loan requirements from sugar mills and distilleries – to put up fresh ethanol production capacity.

And, at the end of the 30-day period, wherein it was examining the new proposals, the ministry maintained that it would be giving in-principle approval to 185 projects for capacity addition of 4.68 billion litres in the coming years. In 2016-17, the installed capacity stood close to 2.70 billion litres. The implementation of projects approved late last year would entail sanctioning loans worth Rs12,500 crore.

The decisive momentum in recent years has resulted in the quick expansion of the ambit of distillery units in the country. According to Sanjay Lakhe, MD, Maharashtra State Co-operative Sugar Factories Federation, emboldened by a relatively friendlier financing regime, the volume of distilleries has certainly grown in recent years in the sugar belt. “Maharashtra today has 112 plants with 2.05 billion litre capacity – 42 in the co-operative sector, 35 in the private sector and 31 are stand-alone units for ethanol production. In addition, 67 co-operatives have in-principle approval for new plants or expansion of their existing units,” he points out. “With Uttar Pradesh emerging as a major sugar producing powerhouse taking care of supply in the north, there is abundant stock in Maharashtra and local producers are keen to take alternative routes.”

A win-win equation

For analysts, the fresh impetus to push ethanol big time is not a shot in the dark. According to them, the government is doing it at the right time when the stage is set to bring benefits to stakeholders across the board. Firstly, it envisages progressively reducing India’s dependence on oil imports to meet its energy requirements. “Meeting over 80 per cent of your oil requirements through imports is not a joke and, by making ethanol a bigger piece of its green basket, the government is showing its long-term commitment to bring in effective solutions,” observes RS Sharma. According to the NITI Aayog report, India’s net import of petroleum was 185 million tonnes, costing the exchequer $55 billion in 2020-21 (expenditure on this account had come down significantly, because of lower offtake after the lockdown and the crash in international prices in 2020). “Most petroleum products are used in transportation. Hence, a successful E20 programme can save the country $4 billion (about R30,000 crore) per annum,” the report says.

Needless to say, savings will go up as the blending quantum shoots up in the medium to long term. Quite interestingly, some news reports (online and print) in recent days have been churning out juicy items saying the fuel price can come down to the range of Rs60 per litre, if ethanol or E100 (the base price of ethanol today in the country) could be used as a stand-alone fuel for which the government has initiated experiments at three locations near Pune.

From the consumer perspective, this could be a huge relief from the present runaway trajectory of over Rs100 per litre for petrol. E100, however, is too far-fetched an idea at this stage but, in the distant future, this could be quite possible, as the Brazil example shows.

-

Sawhney: adding distilleries

When further dissected, the government intent reveals a set of milestones, which it is hoping to achieve in the near to medium run. For instance, the demand projection for ethanol in the next four years entails a nearly 150 per cent jump vis-à-vis the existing base – 10.16 billion litres in 2025-26, as against 4.37 billion litres in the current fiscal (see table). And, the roadmap prepared by NITI Aayog also envisages a modest increase in non-sugar capacity with grain-based capacity rising to a staggering 4.66 billion litres, as against 1.07 billion litres in 2021-22 .

To expedite the affair on this front, the government, as per the NITI Aayog vision paper, has a target of setting up 12 commercial plants and 10 demonstration plants of Second Generation (2G) bio-refineries (using lignocellulosic biomass as feedstock), set up in areas with sufficient availability of biomass so that ethanol is available for blending throughout the country. These plants can use feedstock such as rice straw, wheat straw, corn cobs, corn stover, bagasse, bamboo and woody biomass, etc.

A timely catalyst

A scaling up exercise of this nature obviously means a grand opportunity for the players in the fray and it has particularly enthused sugar manufacturers, as it paves the way for them to create a new commercial vertical at a much brisk pace than in the past. “A back of the envelope estimate suggests that 20 per cent ethanol blending means an additional investment of Rs45,000 crore and much of this is expected to fructify in the next 24 months. Every established sugar manufacturer has drawn a capex for it,” says Tarun Sawhney, vice-chairman & managing director, Triveni Engineering & Industries, which is a leading sugar manufacturing firm in the country.

Sugar industry observers vouch for the fact that the emphasis on ethanol will prove a timely catalyst, as the country is over-producing sugar and taking care of the surplus is turning out to be an issue. The total domestic consumption is in the range of 26 million tonnes annually while the cumulative output has exceeded 30 million tonnes.

Last year, the government had allowed 6 million tonnes of exports which enjoy subsidy support from the government. But, this provision under India’s commitment to WTO will cease at the end of 2023 and, considering the fixed price mechanism for sugarcane prevailing in India and the subsidy support, Indian sugar will not be price competitively in the international market.

“During the last two to three years, domestic sugar production has not been volatile. There has been satisfactory buffer stock. The focus on ethanol will help in addressing the over-supply situation. That is why sugar manufacturers are putting forward their integration drive so aggressively,” says Anupama Arora, VP & sector head, ICRA.

“As the government cannot provide subsidies on sugar exports after 2023 due to WTO norms, sugar manufacturers will now be able to divert that sugar for ethanol purposes,” concurs Bharat Bhushan Mehta, whole-time director, Dalmia Bharat Sugar & Industries. The company produces 800 million litres of ethanol per annum and plans to augment its ethanol manufacturing capacity to 150 million litres per annum from January 2022 onwards.

“With this capacity expansion, Dalmia Bharat Sugar will divert about 150,000 tonnes of sugar for ethanol production, as against 60,000 tonnes now. The expansion will happen at the company’s Jawahnarpur, Nigohi and Kolhapur plants. Also, one new distillery will be set up at Ramgarh,” Mehta adds. Other big boys of the Indian sugar industry also have similar plans. For instance, in a recent investor presentation, Vivek Saraogi, MD, Balrampur Chini Mills, had highlighted the green signal from the company’s board to set up a Rs425 crore 320 kl per day distillery facility which will become operational from December 2022.

“The investment will result in higher efficiency leading to better recovery of ethanol from juice, which will add to the bottom line with a decent payback period. We will continue to strengthen the ethanol business of the company, going forward, as we believe the government’s policy on ethanol is a game changer for the sector to become self-sustainable,” he commented.

-

Mehta: ready to join the club

Triveni too has planned a capex of over Rs250 crore to spruce up its distillery base. “We have just announced two more distilleries (in addition to the existing two), which will take our production capacity from 320 klpd to 540 klpd by the end of this calendar year. So far, we have been looking at distilleries which can deal with molasses in some form. Now, we are setting up a distillery, which will make ethanol from sugarcane juice and it will be the first such distillery in north India. Our second distillery will be grain-based,” says Sawhney. Triveni sugar is setting up new units in Muzaffarnagar and Milak Narayanpur in Uttar Pradesh.

The move has also enthused farmer associations, especially those rooted in Maharashtra and Western Uttar Pradesh – the two leading sugar manufacturing hotspots in the country. “This emphasis on ethanol production should have been brought in ten years back. Our late leader Sharad Joshi was quite vocal in the 2000s that an evolved ethanol business will help both farmers and sugar mill owners,” says Anil Ghanwat, president, Shetkari Sanghatana.

Incidentally, Ghanwat was included in the committee set up by the Supreme Court last year to examine the government’s agri reform proposals after the farmers’ agitation had reached its crescendo in and around Delhi, as also in some north Indian states. Surprisingly, leaders of other farmer factions, who have been vehemently opposing agri-bills are in favour of promoting ethanol. “In the event of a sugar production glut, the payment by sugar mills to farmers becomes an acute problem. But, with a new avenue for sales to the mills backed by commitment from the OMCs, we can expect better payment conditions for farmers and a better financial eco-system in the business,” says Pushpendra Singh, president, Kisan Shakti Sangh, an active association in Uttar Pradesh opposing farm bills tooth and nail.

The flip side

But there still remain some critical issues, which observers are highlighting as the flip side. For instance, the pragmatism of encouraging the cultivation of sugarcane (the main feedstock) and paddy (as a supplementary production source), two of the leading water guzzling crops, is being questioned, considering the fact that India is slipping into the water-stressed countries list, with depleting underground water levels, particularly in many strong agrarian pockets.

Last year, a task force on the sugarcane and sugar industry constituted under the chairmanship of Ramesh Chand, professor & member (agriculture), NITI Aayog, estimated that sugarcane and paddy combined use 70 per cent of the country’s irrigation water, depleting water availability for other crops. “Hence, there is a need for change in crop patterns, to reduce dependence on one particular crop and to move to more environmentally sustainable crops for ethanol production,” the recent roadmap report of NITI Aayog underlines. Cereals, particularly maize, and second generation (2G) bio-fuels, with suitable technological innovations, have been cited as environmentally benign alternative feedstock for ethanol production. “This is a matter of serious concern even as the present government and other stakeholders need to be complimented for putting in a sincere effort and trying to build a sizeable scale in alternative fuel. Brazil, however, has developed a stronghold in sugarcane mainly on the basis of natural rainfall support. But, here, if you are relying on underground water or surface canal water for more sugarcane production to shore up ethanol production, that would be a major mistake,” says Anil Razdan, former additional secretary, petroleum & natural gas.

“In principle, there is nothing wrong with what the government intends to do. But, the country’s dependence on sugarcane to dramatically build scale in the next four-five years in ethanol is worrisome. Instead, if you use your resources for other cereals or edible oil plantations, it can create a world of difference to your agri-output,” concurs Hemant Mallya, senior programme lead, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEA), a noted policy research institution on environmental issues.

-

Ghanwat: good for farmers and mill owners

Mallya strongly advises that in the non-sugar feedstock category, the government should incentivise millet which does not need too much water. “A lot of people are looking at maize as a strong alternative but even this crop consumes a lot of water. Plus, there should be urgent initiatives for producing ethanol by using our vast resources in terms of municipal wastage (275 million tonnes) and crop residual wastage (about 200 million tonnes),” he adds.

But, within the sugar circle, there are senior representatives, who strongly refute the theory that sugarcane cultivation remains in a traditional mode and is increasingly becoming a burden, when the water resource is under stress. “If you look at the total acreage for sugarcane, it has mostly remained constant for the last 15 years – in the range of 5 million hectares. But the productivity has grown sharply from 22 million tonnes to a peak of around 33 million tonnes. This has happened because at many places farmers and sugar mill owners are deploying more scientific means of irrigation for better yields,” argues Abinash Verma of ISMA.

“In places like western Uttar Pradesh, which is now flush with sugar mills and distilleries, sugarcane farmers work in close coordination with local production units and are their captive strength. Imagine what will happen to these mills if these farmers decide to switch over to any other crop on a large-scale basis. Farmers in the region are also glued to sugarcane because it is a robust crop which can’t be destroyed by stray animals,” says Pushpendra Singh.

Meanwhile, in the gigantic exercise of creating pan-India infrastructure for plants, distilleries, storage and distribution depots and even transportation means for increasing ethanol volume (centred in five states, particularly in Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka, which are market leaders in sugarcane production), the private sector has begun building a war chest for capacity enhancement or greenfield capacity addition.

But, more critical is how oil marketing companies will expand their ethanol-centric capacity – particularly, their 2G plant networks (an expensive affair but inevitable for non-sugar feedstock-based operations), when they have not been able to do much in the past.

A questionnaire sent to Indian Oil and HPCL, the two major marketing firms, in this regard remained unanswered. But according to a senior industry captain, these companies will act fast now that they have the mandate from the government to drive the show to the next level. Mehta of Dalmia Sugar meanwhile points to a serious anomaly on the back-end infrastructure side, which needs to be corrected. “One thing we would like to point out, on the basis of our personal experience supplying to at least 20 different depot locations, is that the sync between the actual requirement of depots and what is tendered by OMCs are a bit misaligned. A more detailed study in terms of the actual requirements of depots will help the distilleries to streamline and plan supplies better.”

Creating infrastructure

Within industry circles, as ethanol has to become an all-India readily available fuel with local level storage and distribution units at strategically important locations, stakeholders are looking at options for better transportation means. “Since plants and distilleries are not available in every corner of the country and creating local level infrastructure will take some time, we would like the railways to come into the picture for the bulk transportation which could be cost-effective. A formal discussion with railway ministry has been initiated,” says Abinash Verma.

-

The private sector has begun building a war chest for capacity enhancement

An equally important issue is how vehicle manufacturers will adjust to the adoption of ethanol at the ferocious pace the government has chalked out, buffeted as they are by a serious slowdown, which began much before the Corona onslaught; sharing the responsibility of the government’s grand vision on electric vehicles (industry insiders say it has taken a back seat now considering a series of constraints and unlikely to take off at a mass level before 2030) and conforming to new, stricter emission norms like the second phase of Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFE II) norms.

Simultaneously, the government’s overdrive mode on ethanol will have to be matched by them and a corresponding response in engine calibration. Though SIAM officials did not respond to our query on their possible action plan on encouraging ethanol usage (Transport Minister Gadkari has asked car manufacturers to develop flex-fuel engines which can also run on Ethanol like in Brazil), a senior industry leader said the technology is available but there would be some practical challenges in the beginning.

“The old vehicles, which are still plying the roads, can be run on E10 blended petrol. But the moment you go beyond that, it could result in corrosion of some components. So, while we upgrade, we should not immediately do away with E10, which should be used as a protective fuel for some time,” he said, while requesting not to be renamed. “Another critical point is: the use of ethanol blended petrol would reduce the fuel efficiency of a vehicle by 4-6 per cent. We have to find a solution for it. A flex-fuel engine vehicle would also be slightly expensive,” adds the official.

Gadkari had announced introducing clear directives for flex-fuel engines in the early part of July. “I am the transport minister and I am going to issue an order to the industry that, not only will petrol engines not be there, there will be flex-fuel engines, where there will be a choice for the people so they can use 100 per cent crude oil or 100 per ethanol,” he said, while addressing a virtual event. Simply put, more interesting elements are all set to be added to the growing ethanol story.