-

I’m keen to promote the concept of strong investment protection agreements that allow UK investors to invest in India with a sense of security, stability and predictability

Dominic Johnson, UK investment minister

India-UK trade

The UK, on the other hand, is looking to establish its credentials as an independent trading nation after leaving the EU and is seeking an Indo-Pacific tilt to its foreign policy.

In 2022-23, India-UK bilateral trade increased 16 per cent to $20.36 billion. India’s exports were $11.4 billion in 2022-23, compared with $10.5 billion the previous year; and its imports stood at $8.96 billion during 2022-23 compared with $7 billion in 2021-22. In terms of total trade volume, the UK ranked as India’s 15th largest trading partner during this period. Yet the potential is huge as India and the UK are deemed natural trade partners.

The potential gets sporadically reflected in our two-way investments. UK companies have made substantial investments of about $33.87 billion in the Indian market, while it is estimated that 900 Indian firms operating in the UK contribute a turnover of $68 billion.

Recently, the Tatas hit the headlines by announcing a 40 GW battery cell giga-factory in the UK. The investment, of over £4 billion, will deliver electric mobility and renewable energy storage solutions for customers in the UK and Europe.

Yet the hiccups in our trade negotiations refuse to go away. Boris Johnson, the boisterous former premier of the UK, had set a Diwali 2022 deadline for the FTA. That didn’t happen as he had to leave office. Johnson was replaced by Liz Truss. The Truss government maintained that it will obviously not sacrifice quality for expediency and will only sign when a deal that serves both nations’ interests has been reached. The Rishi Sunak government is now left holding the baby and the bathwater. Sunak has stressed that he won’t sacrifice quality for speed in trade talks.

Clearly, the UK is setting tough standards for India to follow. “I’m keen to promote the concept of strong investment protection agreements that allow UK investors to invest in India with a sense of security, stability and predictability,” remarked Dominic Johnson, UK investment minister, recently.

“And, I might say vice-versa. India would gain from liberalising its financial services to resemble more closely the British system, and that British expertise could help that happen, outside the terms of any future FTA. The more India can do to formalise its economy and to harmonise its trade and tax systems and licensing regimes across India, the better.”

Neither Sunak nor Prime Minister Narendra Modi would like to conclude a deal with strong political ramifications so close to elections in their respective countries. Thorny issues in the India-UK FTA negotiations are intellectual property rights (IPR), ROO and services. So far, 14 out of 26 chapters have been closed during the bilateral FTA negotiations.

IPR protocols

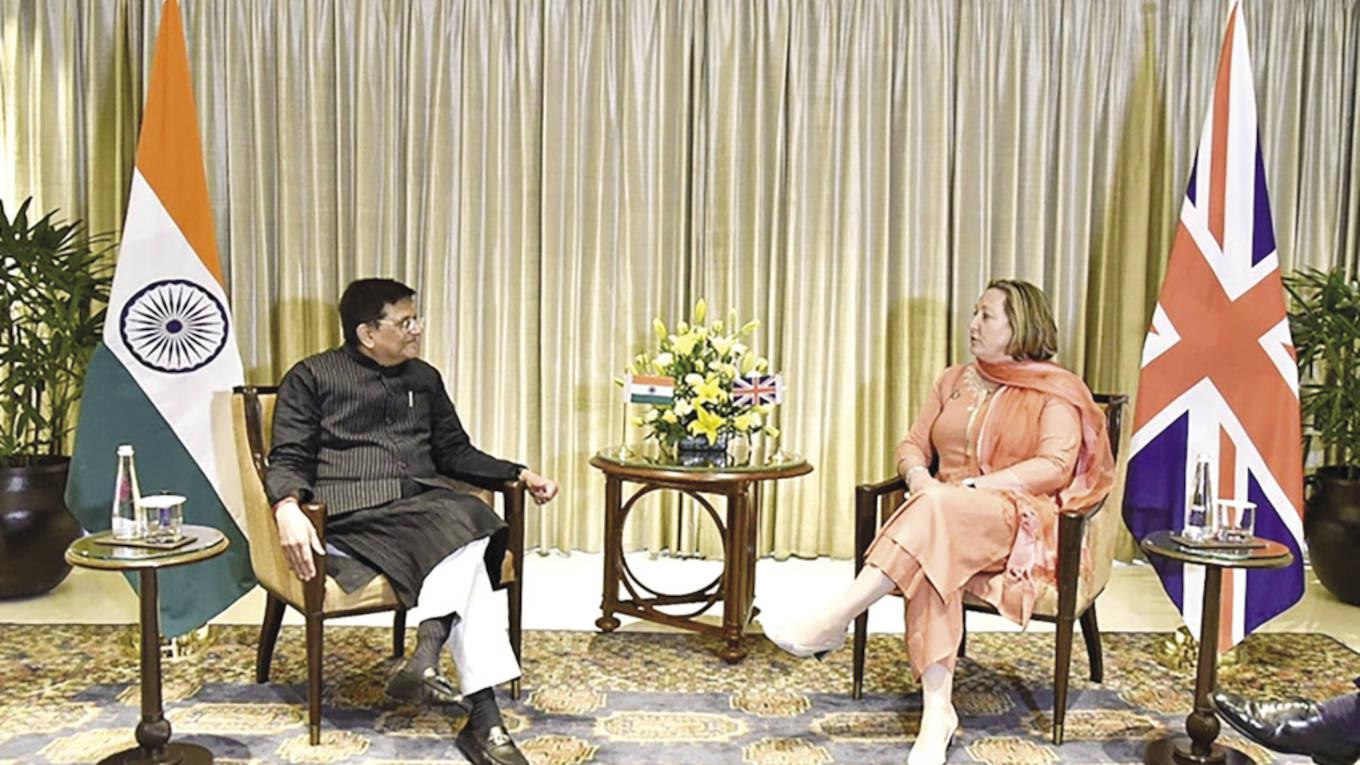

During his visit to London on 10-12 July, Union Commerce & Trade Minister Piyush Goyal said that India is working with countries like the UK to modernise its IPR protocols. Goyal met with UK Secretary of Trade Kemi Badenoch and the two ministers discussed identifying and focusing on low-hanging fruits, “which included the closure of several chapters in the negotiations.”

Nigel Huddleston, the UK’s minister for international trade, said that progress has been made on half of the chapters in the FTA and that efforts are underway to finalise the negotiations as swiftly as possible. While tariff reductions on Scotch whiskey, automobiles, etc, would be welcome, Huddleston stressed the significance of addressing non-tariff barriers, streamlining paperwork and using digital signatures to facilitate smooth trade operations.

-

Goyal with Kemi Badenoch: focusing on low-hanging fruits

As the back-and-forth talks continue between trade negotiators, the Modi government too as a counter-thrust established certain ‘red lines’ – areas where it will not compromise. These include the production of generic medicines, regulatory data protection, and the inclusion of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in government procurement.

Regarding IPR, India will not yield to demands for data exclusivity and patent term extensions, as these would hinder the production of affordable life-saving generic drugs within the country. Trade officials claim that this is a stance that cannot be compromised.

Data protection

Data exclusivity grants exclusive rights to companies over their drugs’ clinical data and can prevent other manufacturers from introducing cheaper generic versions, even in the absence of patent protection. Effectively, data exclusivity could be exploited to extend the patent life of a drug beyond its original term by making minor adjustments to its formulation and securing rights over the clinical data. Patent term extension involves granting a longer period of patent protection to compensate for the time spent awaiting regulatory approvals.

India also refuses to undertake any commitments in the realm of data protection and related areas, such as data localisation. The absence of a digital policy in India necessitates the inclusion of a carve-out specifically addressing this concern within the proposed FTA.

Government procurement is another area where India is open to negotiations but its public procurement policy is designed to support and foster small and medium enterprises and any compromise for the Indian side in this regard is not acceptable.

However, for the record, commerce ministry officials stated at a presser on 15 June that India-UK FTA negotiations have substantially concluded for 14 chapters out of the total 26 chapters. Both parties were coming closer on the discussions on labour, environment, and ROO.

The remaining areas or chapters require both parties to align their expectations. The UK demand for tariff reductions on Scotch whisky and automobile exports to India continues to be a problem but solutions were not far off.

It has been reported that one strategy India could be willing to adopt to allow UK passenger vehicle imports is via a tariff rate quota (TRQ). India has one with the UAE, for example, for gold imports. The TRQ would place a ceiling on the number of vehicles imported from the UK at a concessional FTA tariff rate.

The import duty structure would ultimately be phased over a specified period of time, say five years. However, it remains to be seen if this strategy would be acceptable to UK trade negotiators and industry.

In the automotive sector, India’s customs duties for fully assembled vehicles vary between 70 per cent and 100 per cent, depending on the specific category. Domestic passenger vehicles sales in 2022-23 were 3.89 million.

Meanwhile, under spirits and wines, India’s import tariff applicable on Scotch whisky is 150 per cent. India’s whisky market share is 97 per cent and Scotch whisky makes up only 2.8 per cent of the market. There is a move to give more concessions to bulk instead of bottled spirits, the idea being that bottling plants will have to be setup in India and this would generate employment.

-

Progress has been made on half of the chapters in the FTA and that efforts are underway to finalise the negotiations as swiftly as possible

Nigel Huddleston, The UK’s minister for international trade

As the UK-India FTA negotiations enter the next round, the UK House of Commons committee on international trade raised concerns about the lack of information sharing by the UK government regarding the trade talks. Areas of concern include India’s Digital Data Protection Bill, which could impose data localisation requirements, non-tariff barriers faced by UK automotive exports and market access relaxations for India in various sectors, such as textiles, apparel, footwear, and horticultural products.

Such relaxations could potentially impact the preferential access that the UK currently provides to developing countries in South Asia, South-east Asia and East Africa. The UK government has been given a deadline of two months to respond to the committee report’s findings and questions

Indian officials say that the overarching focus from New Delhi’s perspective is to ensure a comprehensive deal without ceding too much ground, given that this deal will serve as a template for all upcoming trade pacts, including the ones being discussed with the EU and the EFTA (European Free Trade Association) countries, such as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

“We are negotiating, we are seeing how we gain in the negotiations… how our interests are protected while we gain from them in the negotiations… so that we don’t end up giving up more,” says a senior government official.

Indian trade experts believe that, before ‘saying yes’ to new negotiations, India must make an assessment of how much will its exports increase post-FTA. The term to focus on is Real Additional Market Access (RAMA). RAMA is the export value of Indian products where non-zero MFN (most favoured nation) duty in partner countries becomes zero post-FTA, and as a result product becomes cheaper than the price charged by the nearest competitor. “RAMA gives a common sense understanding of the likelihood of an increase in exports post-FTA,” says Ajay Srivastava, co-founder, Global Trade Research Initiative.

India should also draw lessons from its weak export performance with FTA partners, which happened because of high tariffs in India and significantly lower tariffs in its FTA partners. Such results could have been easily anticipated even before the signing of the agreements.