-

Though the air has been rife with tension since 15 June, when 20 Indian soldiers were killed in the line of duty – a first in more than four decades – within the government, there is an underplayed optimism about a possible resolution

For all practical purposes, the India-China relationship has broken down at two levels. The first is with regard to the border management framework that has been in place for close to three decades. It is clear that China no longer sees the advantage of maintaining peace and tranquillity on the border – and is keen to maintain this peace only on its terms, after wresting territory over which it has no legitimate claim. This is unacceptable to India. The second is with regard to the broader framework of the relationship. For years, India has convinced itself that the dynamic with China has both a cooperative and competitive element – and while this was true, it is also now clear that the competitive dynamic has become sharply adversarial.

So, the tensions have continued to simmer as both sides refuse to yield ground. Four days after the Jaishankar-Wang meeting, China’s envoy to India, Sun Weidong, reiterated in a press interview Beijing’s claims that India had “illegally crossed” the LAC in a bid to change the existing status quo. Beijing insisted that the onus of disengagement was on New Delhi, implying that India should make unilateral concessions. Addressing Parliament, which met after five months, defence minister Rajnath Singh sent out a loaded response. India, he said, is “very serious about issues of sovereignty” and the country is prepared for “all contingencies” to ensure that it is maintained. Detailing the meeting in Moscow between him and his Chinese counterpart, Wei Fenghe (also in Moscow), Rajnath said he made it clear at the Moscow meeting that India wants to resolve this issue in a peaceful manner and “wants the Chinese side to work with us”. But “there should also be no doubt about our determination to protect India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” A similar stance was taken by Jaishankar when he met his Chinese counterpart in Moscow, Rajnath said.

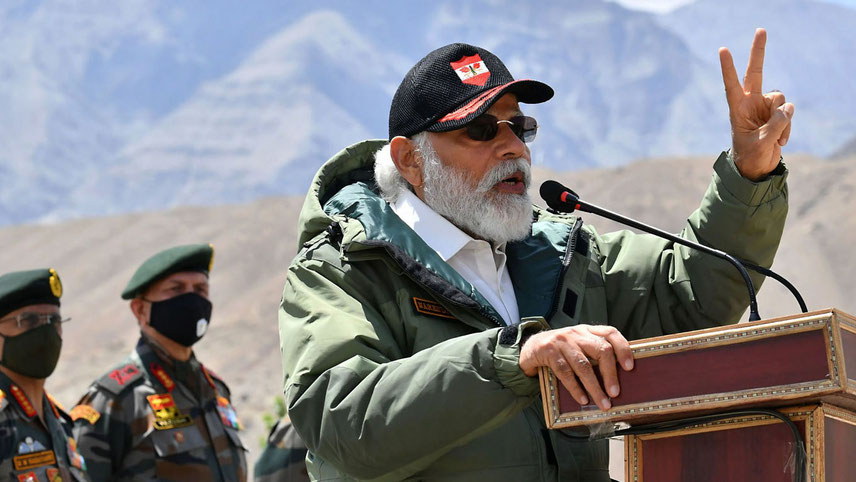

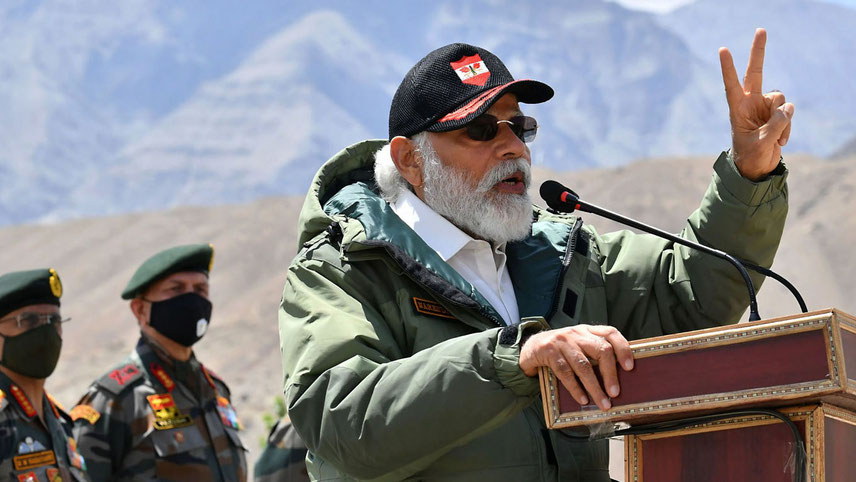

Modi stays away

The fact that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, normally given to hogging the limelight in foreign affairs, delegated the task of dealing with a truculent China to his ministers, showed how high the stakes were this time around. By asking Rajnath and Jaishankar to talk to the Chinese, Modi was perhaps insulating himself from the political blowback of a failure in negotiations which would invite a military confrontation.

-

Jaishankar and Wang in Moscow: will it change the course of the PLA’s expansionist game plan? Picture credit: Deccan Herald

But then, as Neville Chamberlain so wisely said, there are no winners in war. India appeared to be conscious of the sagacity of this statement. At a time when the economy is contracting and Covid-19 infection figures are rising, a war with China, even a limited one, would be like a triple whammy to India. So far, India has been forced to choose relative discretion over valour on China because its real weakness, all along, has been an inability to build rock solid defence capabilities and it also depends on large-scale imports. It is only now, after six years in office, that the Modi government has launched a drive to promote indigenous defence manufacturing.

Experts aver that despite some brave noises, India does not want war and will try to avoid it. Even a limited war will divert India’s attention and resources, plunging the nation into a serious crisis. Like it or lump it, the plain truth is that China today is way ahead of India in respect of the economy, military power, and technological progress. China has made all-round exponential progress to become a colossal force in the world while India is still considered an emerging power.

Also, the Chinese economy has got inextricably intertwined with the global economy and that of India as well. It is thus in a position of shaping economic events and influencing trade flows.

For instance, having managed to stage a quick recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, China is now driving up the demand for resources and raw materials. This includes chemical products and ores – two of the goods which India exports to China. India’s exports to China surged 78 per cent year-on-year in June while its imports dropped 42 per cent during the same period. July again saw a positive growth in exports to China (along with South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam). The inward shipments from China, on the other hand, contracted almost 60 per cent during the January-July period. This was a result of the punitive measures announced by New Delhi, as well as a drop in demand in India.

Official stand

The Modi government’s official stand on the current downturn in bilateral ties is that the border issue remains unresolved as China, historically, ‘does not recognise the current boundary’. There is no commonly delineated LAC in the border areas and no common perception of the entire LAC which stretches from the Karakoram mountain range in the north to the trijunction with Myanmar in the east. The difference in perception has led to the present face-off at the LAC. It says that China has illegally occupied 38,000 sq km of India’s territory in Ladakh. Also, the deployment of troops along the LAC by China is against the 1993 border agreement. Yet, for some strange reason, the government has failed to pin down China at international forums for violating all the three agreements that have been signed for maintaining peace and tranquillity on the border.

-

Modi: has he failed to figure out the China conundrum? Picture credit: Daily Sabah

The government’s enunciation of its official position has not satisfied the opposition Congress party which, sensing an opportunity to pick holes in Modi’s strongman image, has demanded that the government explain the ‘real situation’ in Ladakh. Rahul Gandhi has been attacking the Prime Minister for misleading the country on Chinese encroachment and “failing to take back the land of our country” which Chinese troops have transgressed into. During the debate in Parliament on the border faceoff, senior Congress MPs asked the government to restore the status quo ante on the India-China border as on April. “You (the government) have to clarify that sovereignty means the status quo ante as in the middle of April. That is the meaning of sovereignty,” former defence minister AK Anthony said.

Though the air has been rife with tension since 15 June, when 20 Indian soldiers were killed in the line of duty – a first in more than four decades – within the government, there is an underplayed optimism about a possible resolution. The optimism stems from a set of reasons. The first is simply the high-level, face-to-face nature of the negotiations. The military-to-military meetings ran aground, with local commanders lacking the authority to make decisions that require political sanction. Thousands of troops from both sides backed by heavy armament remained massed on both sides of the border. Jaishankar’s meeting with Wang Yi, preceded by that of Rajnath and his Chinese counterpart, were the first genuinely high-level – and physical – interactions between the leadership of the two countries since the border crisis began.

A second reason is the instability inherent in the massive military mobilisation all along the Himalayas. The swift Indian military deployment along the unoccupied and strategic heights near Spanggur Tso and Finger 4 was a signal to China that even for the two largest armies in the world, this particular border is impossible to defend and hold in its entirety, all year round. Reportedly, China made some initial territorial gains, but it wasn’t difficult for India to make similar incursions. With both armies having lost lives in a skirmish that involved the use of brute physical prowess, wired clubs and stones, rival armies moving dangerously within firing range of each other, and shots being actually fired at LAC for the first time in 45 years, the confrontation has become more dangerous than similar incidents in the recent past.

A third reason is that India’s economic sanctions, against both digital and physical products, and its technology alignments with the United States, will translate into a lost opportunity for China. New Delhi reckoned that the issue was as much about the erosion in valuation that Chinese tech companies suffered after India banned their apps as it was about Beijing’s ambitious plans to establish a Sino-centric global standards regime being challenged. The message India sent out was that the cost for eight kilometres of land along Pangong Tso Lake was high and going to become higher. The entire bilateral relationship was at risk.

-

Rao: a constructive move. Photo credit: DNA India

In the long term, of course, India will have to keep on building internal economic – and subsequently military – capabilities to compete with China in any meaningful way. This will certainly not happen if its economy continues to contract or if it has a minimal positive growth rate. In such a scenario, the government will have more limited resources; crucial military modernisation plans will get halted or slow down; the power of Indian businesses to compete globally will shrink; the Indian market will suddenly not appear as attractive; the government will have to shift focus to address domestic economic distress and possible social unrest; New Delhi won’t be able to take autonomous economic decisions to reduce dependence on China; and India’s ability to buy goodwill in the neighbourhood will become more limited.

On the whole, Modi’s ability to handle the China challenge will also set the course of the national political debate. So far, he has not come out in flying colours. For a politician who has visited China nine times, four times as chief minister of Gujarat and five times as Prime Minister, he should have figured out the China conundrum by now. He seemed to have overlooked the fact that the seven decade-old boundary dispute – which resulted in a short-lived but full-blown war in 1962 – had never reached a resolution. His wary predecessors had always followed a policy of managing China amid the border differences. Modi, on the other hand, in a fit of bravado had joined hands with China’s Xi Jinping to grandiosely declare that 2020 will be the year of India-China cultural relations and people-to-people contacts. This was a romantic illusion at best. It also turns out that his highly-publicised summitry with Xi made for only colourful optics. The end result is that for the first time since 1962, public sentiment in India has turned extremely hostile towards China. Within China too, nationalist sentiment against India is growing.

Five-point roadmap

On the face of it, the two sides have framed a five-point roadmap for easing tensions on the disputed border and speeding up the disengagement of troops. The points include dialogue aimed at quick disengagement, maintaining proper distance between troops of the two sides and easing tensions, abiding by all agreements and protocols on border management, and working on new confidence-building measures once the situation eases.

Former foreign secretary Nirupama Rao, who had also been India’s ambassador to China, said that issuance of the joint statement was a “constructive move”. “It suggests that the two agreed on the need to reflect some shared understandings reached in the course of their discussions,” she noted. Besides, even though many of the points may have been previously verbalised, a joint statement “offers a degree of reassurance that the focus is on building common ground based on these principles.”

-

“Today, the bottomline for the relationship is clear: peace and tranquillity must prevail on the border if progress made in the last three decades is not to be jeopardised. The border and future of ties cannot be separated”

S. Jaishankar in his book

However, there are experts who hold a different view. They have noted that both countries hadn’t made any mention of the restoration of the status quo on the LAC as it existed in April or set any timeframe for completing the disengagement and de-escalation. “The India-China joint statement on border disengagement somehow doesn’t inspire. The Chinese don’t seem to have agreed to restore the status quo ante. There are no timelines,” says former ambassador Vishnu Prakash. “The understanding on quick disengagement is vague at best. It will be a miracle if these commitments are honoured,” he added.

Indeed, the joint statement seems to be more concerned about managing the immediate tensions on the ground. For example, point number two says that the two countries agreed that border troops ‘should continue their dialogue, quickly disengage, maintain a proper distance and ease tensions’. The “proper distance” points to the understanding reached at the corps commander-level talks on 30 June but never implemented, where they agreed on a buffer zone between the soldiers of the two countries at eastern Ladakh.

While the main takeaway from the joint statement is that China has been made to give a written commitment, which can be held up in future negotiations, most of the five guiding principles are open-ended, which means that it would be difficult to pin down China on the exact wording as they have previously never agreed to India’s position but continuously claim that they are acting within the perimeter of the pacts. Perhaps, the next meeting of the corps commanders will make it clear if China is going to be helpful and help to de-escalate the situation. While the Chinese have agreed to hold a meeting soon, no dates have yet been confirmed.

Time is of the essence

Lt Gen HS Panag (retd), a reputed defence commentator who headed the Northern Command and Central Command, feels that time is at a premium because winter sets in by 30 November. “While the disengagement process, when finalised, will take seven-10 days to implement, the de-escalation of additional troops inducted is likely to take nearly a month. This is longer in our case, as both the roads to Ladakh close by 15 November. In case the peace process fails, both sides may either have to settle for maintaining the volatile status quo or seek to make strategic or tactical gains before the winter sets in. It is pertinent to mention that in 1962, the PLA commenced its offensive on 18 October and announced a unilateral ceasefire and withdrawal on 19 November”, he says.

Before Jaishankar met Wang, India repelled at least two attempts by the PLA to intrude into Indian territory across the LAC. Indian troops doggedly held on to strategic positions on the southern banks of the Pangong Tso. The escalation in tensions in eastern Ladakh was not surprising. With both armies, mobilised in large numbers and staring at each other in close proximity, it was but natural that skirmishes would happen — especially when one army, PLA, wanted to change the facts on the ground and force India to accept a new reality. Whether Jaishankar’s meeting with his Chinese counterpart will change the course of the PLA’s expansionist game plan remains to be seen.

-

Is it that China this time around has decided that it is comfortable with a hot LAC, and an outright adversarial relationship with India?

In dealing with China, India has always had to figure out what China really wants. Is it that China this time around has decided that it is comfortable with a hot LAC, and an outright adversarial relationship with India? If that is so India has no choice but to prepare itself in the military, economic, diplomatic domains and respond accordingly. Or is it the case that China has misread Indian motivations, that apprehensions can be allayed and Beijing can be persuaded to disengage and de-escalate? If that is so, it will help tackle the immediate crisis — even though the long-term orientation of the relationship will still be troubled. India must hope for accommodation, even as it prepares for confrontation. So New Delhi has to follow this calibrated strategy of not leaving anything to chance. This explains why the army has begun preparing for a long haul in eastern Ladakh, rushing in equipment and emergency gear required to operate in sub-zero winter temperatures.

Of course, hardliners in India want Beijing to understand that the terms ‘disengagement’ and ‘de-escalation’ mean only one thing: a return to the status quo ante. They may hold the government politically accountable for this. That is why the China challenge is the greatest challenge Modi has faced in his six years in office.

On its part, India has provided an opportunity for a genuine settlement. Though not evident in its recent actions and statements, saner voices, not just in India but in the continent, are hoping that China’s fabled statecraft, wisdom and pragmatism will reassert itself.

Finally, India and its leaders should wake up to the reality and not relapse into romantic nostalgia about past India-China conversations that compared the two nations to rising powers and civilisation states that will make it to the fourth industrial revolution in, as Jaishankar recently said at an Indian Express ‘adda’: “The same sort of parallel timeframe”. Such a storyline of two Asian giants rising could have been plausible three decades ago but now makes no sense as China has overtaken India on every count, except perhaps our democracy, and is now strong enough to cock a snook at even the United States, almost at will.

While India has sought to address the power imbalance by building its border infrastructure and diplomatically engaging with other countries to an extent in the recent past, a strong military cannot be built with budgets that just don’t grow. It also needs manufacturing prowess and greater technological capabilities, a task rendered difficult if human development indicators and per capita income rank India in the bottom third of countries.