-

Kumar and Modi: leading the charge

In 2005, when Kumar first came to power, he had promised that people would not have to go outside the state for their livelihood. However, little has changed, as migrant labourers from Bihar have spread out in the country in states that offered substantially attractive daily wages, like Kerala (Rs1,500 per day) or Telangana (Rs1,200 per day). Bihar’s daily wage figures are just Rs300 per day.

Economic growth

According to the state’s Economic Survey for 2019-20, Bihar clocked a growth rate of 10.53 per cent in 2018-19, as against the national average of 6.8 per cent. It recorded an average growth rate of above 10 per cent in the past three consecutive years. The main drivers of the economy, which have helped the state register double-digit growth, include air transport (36 per cent), other services (20 per cent), trader and repair services (17.6 per cent) and road transport (14 per cent), according to the 14th Bihar economic survey, tabled in the state assembly.

The BJP-Janata Dal (United) government argues that Bihar, unlike the state of Jharkhand, which bifurcated from it, does not have the benefit of raw materials or minerals to boost its economy. Whatever growth Bihar has logged in recent years is due to public investment, contends Kumar. He also feels that it may be difficult to sustain the growth rates, unless private investment comes in.

However, he is on record as saying that Bihar will not attract private sector investment, unless it gets special status. Another reason for the special treatment for his state is that Bihar lags behind the national average in important economic parameters, such as poverty line, per capita income, industrialisation and social & physical infrastructure. Previous chief ministers, who also failed to build up an industrial base in the state, had also voiced such a demand.

Is special status the only mantra to attract investment? Why should any businessman come to invest in Bihar when, despite Kumar’s attempts at streamlining the administration, small horror stories still greet him as soon as he lands in Patna? This is why, apart from low investor interest from within the country, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has, by and large, shunned Bihar – evident in the fact that, for Bihar and Jharkhand, it stood at a tardy $119 million during April 2000-March 2020.

Bihar recently bagged a poor 26th rank (out of 36 states and Union Territories) in the ease of doing annual business rankings, released by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman. The ranking is based on the business reform action plan (BRAP) 2019, launched by the Department of Industrial Promotion and Internal Trade (DIPIT). It is based on the performance of states on 180 reform points, covering 12 business regulatory areas, including access to information, single-window system, labour and environment, with the larger objective of attracting investments and ease of doing business. Ram Lal Khaitan, president, Bihar Industries Association, attributed the low ranking of Bihar to lack of overall industrial development.

“The BRAP rankings reflect the fact that the level of industrialisation is extremely low in Bihar. There is also a lack of supporting infrastructure, such as transportation and hospitality, which hampers the ease of doing business in the state,” he said. “I run around 11 businesses in Bihar across several industries, including plastic, transport and fabrication,” Khaitan added. “I can tell from my experience that the facilities provided to businessmen in the state are below par.”

-

Tejashwi: too small for his father’s shoes?

According to a retired, senior state government official, “Almost Rs1,000 crore worth of investment went out of the window, leaving many people unemployed”. A year later, the Bihar government’s social welfare department came out with a report card, which claimed that, after the introduction of prohibition in the state, “there has been significant reduction in violence against women and girls in homes, public places and during festival and social functions”.

Special status validity

It is against such a backdrop that Kumar’s demand for special status for Bihar appears as an exercise meant to pass the buck. The Constitution of India does not contain any provision for special category status to a state. It will be difficult for any central government in New Delhi to grant this status to Bihar, while denying it to, say, Andhra Pradesh which, after bifurcation, was saddled with the task of building a new capital. There are exceptions, of course, which can be made on the basis of the fifth Finance Commission’s recommendations in 1969, to provide certain disadvantaged states with preferential treatment in the form of central assistance.

This means that the Centre pays 90 per cent of the funds for all centrally-sponsored schemes in a state granted special status, as opposed to those that are not, which pay out 70 per cent. In 1969, Jammu & Kashmir, Assam and Nagaland were granted special category status. Eight more states were added to the list in the following years, including Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim, Tripura and Uttarakhand.

The parameters required for a state to be granted special category include: hilly and difficult terrain, low population density or sizable share of tribal population, strategic location along borders with neighbouring countries, economic and infrastructure backwardness and non-viable state finances.

Bihar has the highest number of backward districts as compared to other states, with 36 out of the 38 districts in the state ranked as backward, reported the Inter Ministry Task Group (IMGT) in 2005. The Bihar CM has argued that since the state is land-locked and is the least developed in the country, its demand is justified since such states are “internationally eligible for special and differential treatment”. Moreover, the state is below the national average on multiple parameters of development.

However, an inter-ministerial group formed in 2011 by then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh rejected the state’s demands after examining its plea on the basis of these five parameters. Kumar had then stated that the group had reached ‘pre-ordained’ conclusions, and that he would continue his demand. Since then, due to its limited revenue receipts, the state government has been dependent on Central transfers and grants for resources.

Small innovations

But all is not lost. Small innovations can help. The state government recently amended the Bihar industrial promotion policy that, for the first time, included wood-based industries in the priority sector. This would help farmers who had taken to agro-forestry and planted species like poplar, teak, banyan and bamboo, on private land.

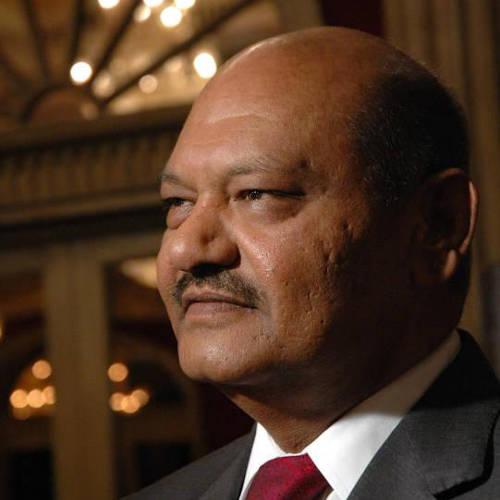

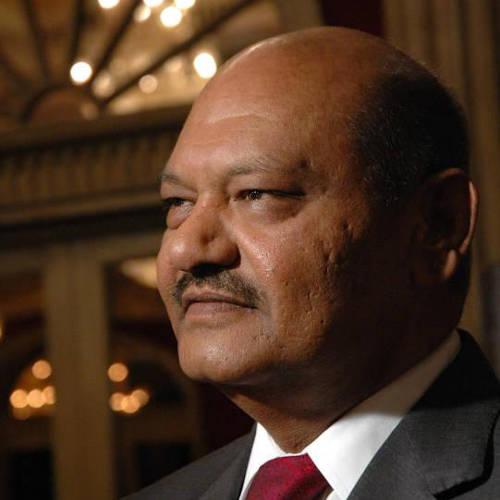

Bihar can certainly do with more of such innovative amendments in its policies. Instead of parroting a demand which will never be accepted by the centre, the state can seriously tap the business leaders who have emerged from Bihar. Indeed, the state has produced a decent crop of business leaders like Anil Agarwal of Vedanta Resources, YC Deveshwar, former chairman, ITC, Samprada Singh, founder, Alkem Laboratories and CS Nopany, former CMD, KK Birla group of Sugar Companies, to name a few.

Agarwal, whose business empire is headquartered in London, has been saying all along that he was still a “Bihari at heart”. He also offered to “explore possibilities” of setting up aluminium, oil & gas, zinc, lead, copper and silver processing units in Bihar. Why has the state not made a serious effort to woo investments from him, including the Rs25,000-crore global university, which he once had in mind for the state?

-

Anil Agarwal of Vedanta: a Bihari at heart; Photo: Sanjay Borade

Bihar’s USP is that it enjoys many advantages over other states. Located in the eastern part of India, the state is neighboured by Nepal in the north, West Bengal in the east, Uttar Pradesh in the west and Jharkhand in the south. This unique location-specific advantage gives it proximity to the vast markets of eastern and northern India, access to ports such as Kolkata and Haldia and to raw material sources and mineral reserves from neighbouring states like Jharkhand and Odisha.

It is one of the strongest agricultural states, with mighty rivers intersecting its fertile land. The percentage of population employed in agricultural production in Bihar is about 80 per cent, which is far higher than the national average. It is the fourth largest producer of vegetables and the eighth largest producer of fruits in India. Food processing, as also dairy and sugar manufacturing, can be easily tapped as fast-growing industries in the state, as can renewable energy. The state has a large base of cost-effective industrial labour, making it an ideal destination for a wide range of industries.

While the impact of returning workers on the economy and the state’s poor health infrastructure will be the subject of research and analysis in the coming years, how this will impact the politics of the state, particularly electoral politics, in the days to come remains to be seen. Among the hordes of migrant workers who returned to the state in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, over 1.6 million can cast their vote in the Bihar assembly elections, according to Election Commission data.

This includes about 2,30,000 people who managed to get registered as voters afresh as part of the updating of electoral rolls. So, the return of millions of migrant workers during the pandemic could change the electoral map in large parts of the state in the event of close contests. The issue of migrant workers has been one of the opposition’s mainstays, as job losses and lack of opportunities have hit families struggling to cope with the outbreak.

There is another aspect that will come into play. As migrant labourers contribute significantly to the rural economy – almost 30 per cent – through the remittances they send back home, the development has hit the rural economy of Bihar. A weak rural economy can make the state vulnerable to basic factors such as malnutrition, healthcare, literacy, etc. The impact is already being felt as prices of vegetables have plunged due to the fact that purchasing power has been eroded. It will be interesting to see whether these issues take precedence over the traditional caste dynamics that have driven election results in the state so far.